skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Introduction

In 2002, I made my first visit to China. I'd not heard of 'blogging' then (there's an interesting history of blogging in Ryan Robinson's blog here) so it was not until 2007 that I started to describe this trip in the post China. At that time, I was still using a 35mm roll-film Canon 'EOS' camera so I was quite sparing in taking photographs and those I did take didn't get scanned and made available on the internet for years.

The 2007 post covers Beijing area (Tiananmen Square, the Forbidden Palace, solo tour of the city and its subway, next day Ming Tombs, Chinese Hospital, Cloisonne factory, the Great Wall), flying to Xian (City Wall, Buddhist Monastery, Big Wild Goose Pagoda, next day Terracotta Army, Flying to Chongqing (board Yangtse cruise ship 'Pinghu', next day start our journey dowmnstream). Then, the description stops with the cheerful comment "I hope to tell you more later".

I didn't return to the topic until I talked about an incident in Beijing right at the end of the trip in the post here. That finally induced me to finish describing my introduction to China but with few pictures to prompt the memory and any contemporaneous notes lost long ago, it will be a little sketchy.

The Yangtse River

The Yangtse cruise proved a good choice as it enabled me to see some of the contrasts China offers, start to understand the importance of the river as an ancient highway and appreciate the breathtaking scope of some of the projects being undertaken in China as it asserts its place in the modern world.

Chongqing-Yichang Yangtse River Cruise (Map: China Discovery)

As described here I'd boarded 'Pinghu' in the dark one evening and the following morning we set off downstream with the weather misty and occasionally rainy. I think Fengdu Ghost City on the northern bank was our first stop, where I gathered contrasting impressions of an ancient temple on high ground and a modern town being demolished virtually by hand prior to inundation. As we continued downstream, there were demonstrations of Chinese arts and crafts on board.

My cruise ship 'Pinghu', viewed from tender taking us ashore.

My cruise ship 'Pinghu', moored midstream in the Yangtse viewed from tender taking us ashore. Note the modern hilltop town top right of the picture.

My cabin aboard 'Pinghu' (Yangtse River Cruise)

Our next visit was to Baidicheng (which means white emperor city), an ancient hilltop fortress and temple complex offering views downstream towards the first of the Three Gorges we would pass through on our cruise - the Qutang Gorge. We had to climb a long, steep path to reach the site and I was rather tempted by the offers of transport to the top by groups of porters using home-made 'sedan chairs' comprising a sort of deck-chair with a simple roof fixed to a stout carrying beam. Resisting temptation, I made it both ways under my own power.

The steep path from the landing place to Baidicheng (Yangtse River Cruise)

I enjoyed wandering around the temple site which commanded good views of the Yangtse River and the Qutang Gorge we would cruise next. I've included a picture of Jan with a carved female guardian lion (Jan is on the left)

Jan and carved female guardian lion at Baidicheng (Yangtse River Cruise)

View of chair lift, suspension bridge and Qutang Gorge at Baidicheng in 2002 (Yangtse River Cruise)

The weather didn't improve as we made our way downstream. It was certainly 'atmospheric' but a bit damp. We passed through the Wu Gorge and went ashore for an excursion on a much smaller boat on a 60 km long tributary of the Yangtse called the Shennong Stream. It's an area of great beauty which I'm afraid we didn't see at its best. The rain sluiced down remorselessly so I didn't risk taking a camera but you can read a modern description of the area here, which talks about 'sampan drifting' in an unpowered, wooden-hulled double-ended craft (sometimes called a 'pod boat' because of its shape). We boarded one of these boats, with two helmsmen, one each end, each provided with a large oar principally used for steering. Of course, initially we were heading against the current so motive power was provided by a line of men scrambling along the bank ahead of us, man-hauling on a substantial rope attached to our vessel. The weather conditions made it difficult for the men to keep their balance and I witnessed a number of near-accidents. To add to the incongruity of the scene, all the haulers had donned plastic ponchos to keep out the worst of the weather. When the helmsmen decided we'd gone far enough, one of the shore party scrambled aboard the boat, bringing the haulage rope with him, leaving the rest of the men to make their way back to the loading point and, presumably, do it all again. Even in the rain and with impaired visibility, it was very pleasant to be silently drifting with the current back to our boarding point and it seemed a different world from the commercial bustle of the Yangtse with its procession of cargo ships and passenger ferries in both directions, occasionally punctuated by the loud exhaust of the hydrofoil ferries. Once safely back aboard 'Pinghu' and with the opportunity to dry-out, our journey continued into the third gorge - Xiling Gorge.

Despite the generally indifferent weather, I spent a fair bit of time outside on the upper deck, trying to absorb the majesty of the deep gorges and trying (but failing) to imagine the changes completion of the Three Gorges would bring, with the river level raised three hundred feet.

Signs on riverbank indicating planned rise in water level. The upper sign indicates 175m above sea level - the planned river level after completion of the Three Gorges Dam (Yangtse River Cruise)

Passing through the Three Gorges of the Yangtse River before inundation (Yangtse River Cruise)

The picture above also shows the mast on 'Pinghu' and the 'christmas tree' effect created by the various branches carrying navigation lights. After dark, I spent some time on the outside upper deck, fascinated by the amount of river traffic still moving, with the different displays of navigation lights indicating each ship's status - anchored, under way, towing.

I was disappointed by the actual Three Gorges Dam site. Although there was plenty of earthmoving going on, I'd failed to fully appreciate that we were passing what would become the base of the dam and that the impressive appearance of a large dam would only appear later. Our cruise terminated at Yichang where a large number of ferries were moored.

Ferry moorings at Yichang (Yangtse River Cruise)

I met up with a local guide who took me by car to the Chinese Sturgeon Museum set up in 1982 which is attempting preservation of this endangered species. There were interesting displays but I found the large, tiled pools housing live Chinese Sturgeon rather depressing, I'm afraid. There's a Wikipedia article here.

Chinese Sturgeon Museum, Yichang (Yangtse River Cruise)

Next, we visited Yichang Museum where there was a very well-displayed exhibition of artefacts from the area, many uncovered during the massive civil works involved in relocating towns along the Three Gorges at a higher level. Finally, I was taken to the Gezhouba Dam with its Navigation Locks allowing ships up to 10,000 tons to by-pass the dam. This project, started in 1970, was completed in 1988 and the 47 metre high dam has a generating capacity of 2.71GW. The scale of the ship locks is impressive but I was particularly taken by the almost continuous stream of pedestrians slowly making their way across the river, in both directions, using the walkways built along the top of the lock gates.

Gezouba: Navigation Lock Gate (Yangtse River Cruise)

My guide then took me to Yichang airport for my internal flight back to Beijing. Back in Beijing, I was returned to the same hotel I'd used on my arrival in Beijing to prepare for my final flight home. It was on a walk in Beijing before my transfer to the international airport that I had the unfortunate brush with the local police described here. Despite that hiccup, it had been a wonderful trip and I'm pleased that I got to see the Three Gorges before the dam was completed.

Related material on other websites

China's Mighty River (1930s article from 'Shipping Wonders of the World).

Yangtse River (Facts and Details site)

Chinese Sturgeon (Wikipedia)

My pictures of the 2002 trip

Beijing, China

Xian, China

Yangtse River, China

When I was growing up, telephone services in the United Kingdom were Nationalised and run as part of the General Post Office (GPO). This was logical since the Post Office handled written messages, in the form of letters, in massive numbers. Telephones offered an alternative, faster, method of sending a message. Back then, few homes had the luxury of a telephone but calls could be made from the familiar, red telephone kiosk. Although this gave you the means to communicate with businesses, its use for personal calls was limited since few relatives or friends would possess a telephone. Urgent communication in matters of accident, sickness or death could be expedited as a written message sent as a 'Telegram'. This involved going to a local post office where you could write a brief message on a telegram form and hand it over the counter. On payment of what seemed a lot of money, this would be transmitted by the Post Office to the office nearest your recipient by teleprinter, printed out on a continuous strip which was cut into short lengths and glued (yes, glued) to another telegram form, placed in an envelope and delivered to your recipient's address by a Telegraph Boy (often on a bicycle). Although my experience of using telephone and telegram services was limited, I became fascinated with telephones and telegraph equipment, possibly triggered by a visit I made, when still at school, to a Telephone Exchange. Back then, exchanges were electro-mechanical, rather noisy affairs, using relays, uniselectors and 2-motion selectors. Reed, crossbar and electronic exchanges were still to appear.

But when I started (unofficially) visiting railway signalboxes as described here, I discovered even earlier telecommunications systems (owned and operated by British Rail) still in use. The block system in use for securing the safe passage of trains from signalman to signalman used an arrangement of single-needle telegraph instruments with codes transmitted by single-stroke electric bells (as outlined in the post here). Telephones used were rather primitive, Local Battery affairs in wooden cases.

Local Battery Omnibus Telephone in wooden cabinet with hinging front. Tiltable carbon microphone and cord-mounted receiver stowed on cradle switch, D.C. bell on backboard. Polarised D.C. ringing-out on two buttons.

The GPO were introducing Subscriber Trunk Dialling into the public network (where customers set up their own long-distance calls without the intervention of an Operator), using 'Step-by-Step' Strowger technology. The first Subscriber Trunk Dialling (STD) call in the United Kingdom was made by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II on 5th December 1958. There's a brief introduction at Subscriber Trunk Dialling (STD) and a Wikipedia article here.

In 1959, the GPO introduced a 'modern' telephone instrument, still featuring a rotary dial. This formed the basis for what became an extensive range of models - the 700-series. Later members of the 700-series even featured push-button dialling! There's an interesting article on the 700-series instruments on Wikipedia here.

In the post The World of Work I talked about working for Contactor Switchgear (Electronics) Limited. The Sales Director had a number of contacts within British Railways and we bid for a number of telephone-related jobs, without any conspicuous success.

In 1966, I decided to set up in business on my own, as outlined in the post Starting my own business. Getting established proved quite difficult and I was quite happy to accept a variety of work. But an introduction to Gerry Gardner led to sub-contract design and manufacture of specialist telecommunications equipment for emergency services. Following the success of this equipment, we were invited to bid for the supply of selective call telephone equipment by British Rail. Manufacture of the resulting contracts led to a period of expansion and development of similar equipment for use as Electrification Telephone systems for British Rail, as described in the post Electrification Telephone Systems for British Rail. Subsequent schemes were supplied to British Rail and other companies like Westinghouse Brake and Signal.

Our equipment was installed in various Power Signal Boxes, including Preston shown in 2013

G.E.C. in Coventry asked us to design and supply telecommunications equipment for a large railway electrification project in Taiwan. Working for the Big Boys mentions some of my experiences and the report here has some recollections from my first visit to Taiwan to assist with commissioning this scheme.

Although we continued to do work in industrial automation (see Visiting Steelworks and Oil & Gas Industry) most work was channeled into telecommunications for railways. British Rail operated a number of large 'Step-by-Step' exchanges to handle internal telephone traffic and they designed their own version of STD (which they called Extension Trunk Dialling) to link these exchanges into one system. We were kept busy maufacturing the racks and relay sets for this scheme.

Two more large projects for G.E.C. followed - one in Brazil, the second in Thailand. These are briefly described in the post Work (part 2). A proposed commissioning visit to Brazil was cancelled at short notice so I didn't get to Brazil until my 'Round the World Two' trip in 2006 (very briefly described here). But I did visit Thailand a number of times during commissioning of that project (the post here outlines the scope, the post here includes a description of a day fault-finding travelling on a railway trolley and the post Thai Railfan Club describes some of the friendships I made).

Standard Telephones and Cables approached us about a complex railway telephone system for use in the Bombay area. We offered to build suitable equipment, but they were keen to manufacture 'in house' so, in the end, we concluded a license agreement. This involved visits to their manufacturing site in South Wales but I was disappointed not to be involved in commissioning the equipment in Bombay - I didn't get to India until 1992 when we commissioned equipment we'd supplied to G.E.C. for a railway telephone system in the Delhi area (see the post My first trip to India).

When we were asked in 1993 to quote G.E.C. for Tunnel Telephone equipment for the Jubilee Line Extension of London Underground, I initially baulked at the idea. None of our existing designs seemed adaptable and, despite the system name, the main function is to provide a high-integrity emergency traction shutdown system. The design challenge appealed to me but I initially assumed the development cost would make our offer uneconomic, as explained in the post Work (part 2). G.E.C. persisted and the supply of Tunnel Telephone equipment became an important, if erratic, source of business but it's so specialised that I tend to think of it as distinct from 'Telecommunications and Jan'. But there is a post called London Underground and Jan.

Related posts on this website

Selecting label 'Work' (or Clicking here) will display all my posts on 'Work' in reverse date-of-posting order. Alternately, Clicking here will display an index list of Titles of posts labelled 'Work' (but this list may not be up-to-date).

[Link URL corrected 26-Nov-2020]

Introduction

In the development of the locomotive engine the initial challenge was to make the machine go. Stopping was less of a priority and early braking systems were rudimentary (or absent). But as designs improved and the weight and speed of trains increased, the need for effective brakes became a priority. The common arrangement was a shaped brake block which could be clamped against a wheel tread, dissipating the energy of motion as heat. Although wooden brake blocks were originally common, their tendency to burst into flame encouraged the use of cast iron which wears away with the friction, neccessitating periodic replacement. To provide more retardation, brake blocks on a number of wheels could be coupled together by a mechanical linkage and operated from a manual handle, often via a screw arrangement. To provide still more brake force, steam-operated brakes were introduced. In the early years, the driver could only operate brakes on the locomotive. The train was braked by the Guard applying a hand-operated brake in the Guard's vehicle at the rear of the train and, in some cases, by assistant Guards applying hand-operated brakes on intermediate vehicles. The shortcomings of this arrangement gave rise to pressure to introduce better braking systems operating on the whole length of the train. Systems using cable (such as the Heberlein cable brake in Germany, described in a Wikipedia article here) and the Clark and Webb chain brake use by the London and North Western Railway in the U.K. for a time were tried but eventually two approaches triumphed, using either air or vacuum.

Braking on the Great Western Railway

Great Western engines were originally fitted with a powerful steam-operated brake which became standardised as a vertically-mounted cylinder, where the piston was pulled upwards when steam was applied. This movement was coupled, by a mechanical linkage co-acting with a screw handbrake, to brake blocks.

In the 1870s, continuous brake systems started to be fitted to trains and the Sanders vacuum brake was trialled by the G.W.R. in 1876. Following these trials, the improved Sanders-Bolitho system started to be installed but, in 1880, William Dean decided that the G.W.R. should design its own vacuum brake system and Joseph Armstrong was tasked with this work. The Great Western, always prepared to be different, set their vacuum brake 'released' level at '25 inches of mercury' whereas every other British railway was content with '21 inches of mercury'. I think it was Churchward (before he succeeded William Dean as Chief Mechanical Engineer) working with Armstrong who made this decision. There's sound logic behind their thinking. 'Vacuum' brakes can be described as 'differential pressure' brakes. The bigger the differential between 'released' (a partial vacuum of 25 inches of mercury) and 'full application' (atmospheric pressure), the greater the brake force which can be produced by a brake cylinder of a given size. Looked at another way, more leakage can be tolerated in at system designed to run at '25 inches' before the braking effort available is seriously compromised. There's a little more on the topic in the post MIC - Brakes.

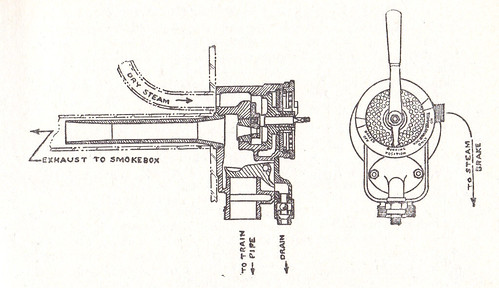

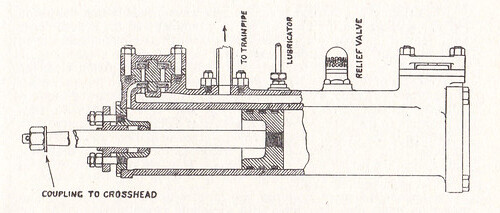

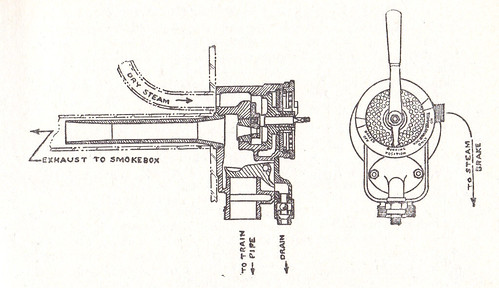

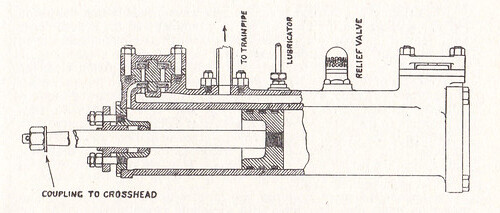

The result was a cab fitting comprising steam and vacuum brake application valve combined with a live-steam ejector, together with a crosshead-driven vacuum pump. The diagrams below, from book reference [1], I think show an early form of the cab fitting and the vacuum pump. Later versions of the cab fitting include the now-familiar small vacuum cylinder to proportionally apply the steam brake when the vacuum brake is applied. When the handle is vertical (as in the diagram) the steam brake is released and, when in motion, the brake pump maintains the vacuum. Moving the handle to the right supplies steam to the ejector to rapidly create vacuum. Moving the handle to the left admits air to the train pipe in a graduable manner to apply braking.

GWR Vacuum Brake Ejector and Application Valve

GWR Vacuum Brake Ejector and Application Valve

Events of Tuesday, 21st May 2019: Leaving Mandalay

Doctor Hla Tun insisted that on Tuesday morning we would travel together to Mandalay Airport in the Monastery car where he would take a flight to Yangon, I would start my long journey home via Bangkok and the two Monastery drivers would return by road to Bagan. To fortify myself for the journey, I made sure of a decent breakfast - fried eggs, beans, roll and butter, yoghurt, orange juice and tea.

Mandalay, 2019: Breakfast at the Hilton Hotel.

Then, whilst savouring the view of Mandalay Hill, the Royal Palace moat and walls from my room, I completed my packing.

Mandalay, 2019: View from my room at the Hilton Hotel.

At the arranged time, Doctor Hla Tun picked up me and my luggage in the Monastery car (already loaded with two lorry tyres purchased in Mandalay required for the Monastery's water tanker which delivers water to various villages around Bagan). On arrival at the airport, there were hasty 'goodbyes' as the Doctor had little time to check in for his domestic flight. I had plenty of time to check-in, mooch around the international terminal and watch the various comings and goings.

Mandalay International Airport: Terminal Layout.

I watched with interest as the Bangkok Air flight arrived, discharged its passengers, their baggage and air freight and loaded baggage and air freight for my flight - PG710 departing at 14:05 on the 2 hour, 1020km flight to Bangkok.

Mandalay Airport: Bangkok Air arrival passing in front of two of the turboprops which provide internal services in Myanmar.

Mandalay Airport: Bangkok Air flight discharging and loading baggage.

A pleasant flight took me to Suvarnabhumi Airport, Bangkok where I knew there would be a fair walk to complete the transfer to my Qatar Airways flight to Doha.

Bangkok Airport.

I'd not been with Qatar via Bangkok before, so I made sure I checked-out the relaxing Qatar Lounge before joining flight QR833, leaving at 20:40. Doha was reached seven hours later, after a 5280km flight.

Qatar Airways Lounge in Bangkok Airport.

Like Dubai Airport, Hamad International Airport in Doha is a major transit hub. The Business Lounge is an excellent place to relax between flights

Part of the tranquil restaurant area in the Business Lounge, Hamad International Airport, Doha.

My final flight QR035 left at 01:50 local time for the seven hour, 5358 km leg to Birmingham.

Arriving Birmingham Wednesday, 22nd May 2019

I slept for part of the journey and, as we neared our destination, was woken by a beautifully-presented simple breakfast, exactly as ordered. I was particularly taken with the imitation 'candle' decorative table lamp - actually electric but with a 'flicker' effect.

Breakfast in the Clouds: Returning to Birmingham by Qatar Airways.

And so I felt surprisingly refreshed when we landed after the marathon 11658 km, 7243 mile journey from Mandalay at the end of another amazing trip to Myanmar!

Related posts on this website

This is one of a series of posts describing my 14th visit to Myanmar. The post Return to Burma is the first post in the series.

Clicking on the 'Next report' link (where shown) displays the post describing the next events. In this way, you may read about the trip in sequence.

Alternately, clicking on the 'All my Burma 2019 reports' link displays all the posts on this trip in reverse date-of-posting order.

All my Burma 2019 reports.

This is the last post describing this trip.

My pictures

All my general pictures on this trip are in the collection of albums Burma 2019

This is the 16th and last post describing an 'Expedition Cruise' with Noble Caledonia in 2020 under the title 'Across the Tropic of Capricorn'.

Events of Friday 28th/Saturday 29th February 2020

I was booked to leave Cairns for home on the noon flight to Melbourne. Most of the Noble Caledonia passengers were travelling later that afternoon but a few, with different flight arrangements, were leaving earlier so a transfer to the airport had been arranged for 09:45 which I joined.

There were brief "good byes" as we were dropped-off outside Departures then I had a brief struggle to get my luggage to the right check-in queue. Fortunately, it didn't take long to complete the fomalities and then, with plenty of time in hand, I made my way to the Quantas Lounge to await my flight at the end of my very brief, but interesting, visit to Cairns.

The relaxed atmosphere in the spacious Lounge was just what I needed and, for once, I was glad of the effective air conditioning as the day was rapidly warming up.

Business Class Lounge, Cairns Airport, Australia

View from Business Class Lounge, Cairns Airport, Australia

I faced a long journey back to my local airport, Birmingham in the UK, comprising four 'legs' with changes in Melbourne, Singapore and Dubai:-

CNS-MEL 3h 15m 1432m 2305km

MEL-SIN 7h 40m 3743m 6024km

SIN-DXB 7h 30m 3633m 5847km

DXB-BHX 7h 00m 3482m 5603km

This amounts to over 1 day actually in the air and, allowing for transit times, well over 30 hours from Cairns to Birmingham. This is really a minor hardship compared with the journeys travellers in previous centuries had to undertake.

The short leg to Melbourne was in economy class. I was already tiring on arrival but managed to find my way to the departure gate successfully for the Emirates Business Class leg to Singapore.

Melbourne Airport, Australia: View during taxiing, with city in the distance.

I was looked after very well on the flight to Singapore, during which I learnt that the same aircraft would be continuing from Singapore to Dubai, after a crew change at Singapore, but that all passengers would have to disembark, transit through security with their hand baggage and then re-board. I'd also been told that there was a new Emirates Lounge at the airport so I thought it might be an idea to have a look at it. Despite the comfortable flight to Singapore, I was starting to get exhausted so I had some difficulty locating the lounge after quite a long walk. I was warmly welcomed and, when I mentioned that I was a bit worried about the walk from the lounge to the departure gate for re-boarding, they insisted on arranging 'Assistance' in the form of an athletic young man pushing me in a wheelchair, which made resuming my previous seat on the waiting aircraft simple and quick.

Having flown Melbourne-Singapore in this aircraft, I transited two security checks to re-board and continue to Dubai!

Safely back on board the two-engined widebody, we took off on our long flight to Dubai. The new crew were as attentive as the earlier crew and I managed some reasonable sleep during the flight. The massive airport in Dubai is a noisy and confusing place at the best of times but, after three flights that day, I was particularly confused but managed to navigate to the relative quiet of the huge Emirates lounge near my departure gate to await boarding.

The Emirates flight from Dubai to Birmingham was on an four-engined Airbus A380. Although I loved the long-lasting Boeing 747 design (now retired from service by major airlines), I've never warmed to the even-bigger A380, although I can appreciate the technical achievement. Boarding involved a lift from the lounge to Departure level, then a short walk to the three air bridges connecting to the waiting aircraft. Waiting to board the lift, I took the picture below.

Boarding the A380 from Dubai to Birmingham in 2020. Note the three air bridges.

Although I love travelling, I always experience a thrill on returning home so, as we lost altitude approaching Birmingham and the familar landscape of England appeared on a dull, February morning, I started to become alert with excitement (and, perhaps, a little relief). We landed safely, I retrieved by luggage without incident and reported to Emirates, who were providing a car home. There was a minor delay waiting for the car, because flights at Birmingham had been subject to some dislocation that morning, but soon I was speeding back home after a fairly serious journey from Australia.

Within three weeks of my return, England had imposed a full lockdown in an attempt to delay the spread of the Coronavirus Pandemic. A three-month lockdown was followed by a plethora of frequently-changed regulations, culminating in a further full lockdown in November 2020 (when I finally managed to complete this post).

Related posts on this website

This post is in the series labelled 'Tropic of Capricorn’. The first post is here.

Clicking on the 'Next report' link (where shown) will display the post describing the next events. In this way, you may read about the trip in sequence.

Alternately, clicking on the 'All my Tropic of Capricorn reports' link displays all the posts on this trip in reverse date-of-posting order.

All my Tropic of Capricorn reports

My pictures

Cairns Airport, Australia

Singapore (Changi) Airport

Dubai Airport, U.A.E.

Birmingham Airport, England

In February 2020, just before the Coronavirus pandemic transformed everybody's lives, I sailed on 'Caledonian Sky' for the second time on a Noble Caledonia cruise titled 'Across the Tropic of Capricorn' which is chronicled in a series of posts. Clicking here displays all these posts in reverse date-of-posting order or alternately, to read the posts in chronological order, clicking here displays the first post and then follow the link to the next post.

I'd first sailed on 'Caledonian Sky' in 2015, on a cruise titled 'From the Coral Sea to the South China Sea' which gave rise to a series of posts labelled 'Caledonian Sky’.

Clicking here displays all these posts in reverse date-of-posting order.The post here describes itself as "more than you wanted to know about the ship", but note that I don't know what changes may have occurred during the subsequent refit of the ship. Another post from that cruise here describes various visits to the bridge and one visit to the Engine Control Room during that trip.

A visit to the Engine Control Room of 'Caledonian Sky' in 2015.

During my second cruise on 'Caledonian Sky' in 2020, there was still an 'Open Bridge' policy, and I made three visits. On 15th February, we were on our way to the island of Tanna, in Vanuatu.

On autopilot, heading for Tanna, on 15-Feb-2020 ('Caledonian Sky' Bridge 2020)

When I returned to the bridge on 24th February, we were heading for Rabaul on East New Britain (part of Papua New Guinea).

ECDIS screen as we head through St. Georges Channel heading for Rabaul ('Caledonian Sky' Bridge 2020).

My last visit was on 26th February, as we made our way towards Port Moresby (Papua New Guinea). As usual, we were on autopilot, with a least one person keeping watch. Suddenly, the calm was broken by three different electronic alarms wailing. I tucked myself in a corner of the bridge, hoping they wouldn't decide to clear the bridge. First, they silenced the noisy alarms. Then, I noticed that the 'swish' of the air conditioning had ceased and that certain indicators had gone blank, so I assumed some sort of power failure.

"Some of the indicators had gone blank" 'Caledonian Sky' Bridge 2020.

There were a few telephone calls and other crew members arrived, including the Captain but the usual air of studied calm continued. The only real change was that one of the crew moved to the Anschutz autopilot console and controlled the small 'conning wheel' whilst carefully studying the heading display so I assumed we were temporarily under manual control.

'Caledonian Sky' Bridge 2020 with the ship being steered manually from the Anschutz autopilot console on the right.

After a few minutes of murmured conversation and more phone calls, we were clearly back on autopilot and the crew member abandoned his position by the 'conning wheel'. The air conditioning restarted and the Captain retired to his cabin, a few yards away. The incident was over.

My pictures

'Caledonian Sky' Bridge (2015).

'Caledonian Sky' Bridge 2020.

Engine Control Room, 'Caledonian Sky' (2015).

In 1988, I became a volunteer at Birmingham Railway Musuem (as it was then known). The post here discusses how, to boost revenue, 'Learn to be a Driver' courses were introduced around 1990. These were instantly popular and there's a little more about the format of these courses in the post here. There was heavy demand for volunteers who could tell the trainees a bit about shunting, signalling and the principles of locomotive engineering. I served in this capacity for a while and then gravitated to Instructor Driver on the 'Little Engine' used on the courses. After some more experience, I was passed out as Instructor Driver on the 400 yard demonstration line with the 'Big Engine', initially 'Defiant' or 'Clun Castle', later various visiting locomotives including 'King Edward I', 'Taw Valley', 'Canadian Pacific' and 'Sir Nigel Gresley'.

'Flying Scotsman' made three visits to Birmingham Railway Museum offering modified 'Learn to be a Driver' courses in 1992, 1993 and 1994 and these are briefly described in the post here).

The line at Tyseley was only short, giving trainees the advantage of plenty of practice in starting, stopping and reversing a locomotive. However, to enable trainees to experience being 'on the road' , hauling a train of coaches, Birmingham Railway Museum made an agreement with the Shackerstone Railway Society to use their 5-mile line (marketed as The Battlefield Line) for Footplate Experience Courses when the line was not otherwise in use for service trains.

In the first 25 years of its existence, the railway at Shackerstone had operated using a variety of industrial steam locomotives so the Birmingham Railway Museum initiative represented something of a step change. The course format retained the 'safety briefing', 'little engine' and 'big engine' format of the Tyseley courses, but the other features were normally omitted. Birmingham Railway Museum marketed these courses, provided the motive power and suitably-qualified footplate crews for instructing on these courses. I was one of the instructors 'parachuted in' from Tyseley (along with John, George, Dave Davies. and Tony M.). I thought it only right to also become a member of the Shackerstone Railway Society as well, with the result that I'm still doing driving turns at 'The Battlefield Line', over a quarter of a century later.

In May 1993, Bullied 'Pacific' 34027 'Taw Valley' arrived at Shackerstone by low loader and, together with pannier tank 7752 the successful courses commenced. 7752 was often used for initial familiarisation of the trainees, running up and down within 'station limits' at Shackerstone. As at Tyseley, 'single manning' was allowed on this engine, with the instructor driver supervising the trainees and acting as fireman. 'Taw Valley' ran with four empty coaches to Shenton, ran round and returned to Shackerstone. Two instructor drivers were rostered for this, one supervising the trainee driver, the other supervising the trainee fireman (or, more often, just did the firing whilst the trainee enjoyed the ride prior to their turn to drive). A guard rode in the coaches.

On 'Taw Valley', I was often rostered with Dave Davies - a 'Southern' engineman to his fingertips, who'd fired Bullied 'Pacifics' out of London. With the withdrawal of steam, he moved onto diesel-electric freight locomotives, becoming an instructor for British Rail. The footplate experience courses through Birmingham Railway Museum re-kindled his interest in steam and he later gained quite a following for his exploits on main-line steam specials. I found him a very good-natured and generous 'mate' and, on these footplate courses, he would often let me look after the trainee driver to give him a chance to show his prowess with the shovel. Eventually, 'Taw Valley' left Shackerstone for work elsewhere.

BRM driving courses at Shackerstone: Bunty and Jan on 7752 (posed for newspaper photographer with 'L' plate) 15-May-1993.

BRM driving courses at Shackerstone: Bunty and Jan on 'Taw Valley' (posed for newspaper photographer with 'L' plate) 15-May-1993

As far as I remember, 7752 was then promoted to giving trainees the experience of running a train to Shenton whilst Shackerstone's then-resident 0-6-0 saddle tank 'Lamport No. 3' took over the role of 'little engine'. 'Lamport No. 3' (Bagnall works number 2670) was one of a batch of six locomotives built for Staveley Coal & Iron in 1942 and put to work in Lamport Quarries, Northamptonshire. I rather liked the engine. It steamed well, pulled well and the compensated springing gave quite a good ride. The setting of the regulator offered easy 'finger-tip' steam control. This is often associated with a tendency for the regulator to leak, but I never remember a problem.

By 1994, pannier 7752 had returned to Tyseley and was replaced by another Tyseley pannier, 7760, which was turned out in red London Underground livery with the running number 'L90'. Although historically correct (both 7752 and 7760 were both part of the London Underground fleet before moving into preservation), I never quite got used to its appearance.

Also in 1994, the locomotive shed at Shackerstone was extended to give more under-cover storage for 'big engines'.

There were a number of visiting locomotives to the Battlefield Line in the late 1990s. Although I got to drive all of them on service trains (except the B.R. 'Standard' 2-6-0 76079), I'm unsure how many were involved in footplate experience courses.

I think there were two visiting engines in 1996 - the 'N2' 0-6-2 tank engine 69523 and the double-chimney 'Jubilee' 45595 'Bahamas'. Around this time, a footplate course full-colour publicity brochure featuring 'Bahamas' was issued.

Part of the pamphlet advertising driving courses at the Battlefield Line (Chris Simmons collection)

Unfortunately, the rather nice shot of 'Bahamas' entering Shackerstone was printed 'mirror-image'. Here it is the right way round:-

'Bahamas' fireman surrendering the single line staff to the signalman at Shackerstone (from the BRM pamphlet but, this time, the right way round!)

In 1997, the preserved Coal Tank, 'Jubilees' 45593 'Kolhapur' and (again) 45596 'Bahamas' were on site. In addition, pannier tank 7762 returned and 0-6-0ST 'Victor' (Bagnall works number 2996, built in 1951 for Steel Company of Wales) was moved by the private owner, Warwick Ormandy, from Tyseley to become resident at Shackerstone.

In 1998, B.R. 'Standard' 2-6-0 76079 was on site (the one visitor I didn't get to drive) together with L&Y surviving 0-6-0 freight tender locomotive 1300 (which, prior to preservation, had been 52322). I really must try to document some of my experiences in this interesting period. In 1998, Birmingham Railway Museum's ambition was to operate regular steam on the main line between Birmingham and Stratford, under the 'Vintage Trains' brand. To accommodate this, the Birmingham Railway Museum Footplate Courses at both Tyseley and Shackerstone were discontinued. Regular 'Shakespeare Express' services started in 1999.

This didn't mark the end of my involvement with instructing on footplate courses. At first, for a while, I was involved with courses on the West Somerset Railway and then, as a volunteer at Peak Rail, I regularly instructed trainees there, until 2019. I'll try to expand my posts describing footplate courses.

After Birmingham Railway Museum discontinued the courses at Shackerstone, the Battlefield Line decided to market a modified format themselves, so I've continued to be involved as required until the Coronavirus pandemic in 2020 prevented footplate courses from being held. The limited operations which have been possible in 2020 are outlined in the post Operations at the Battlefield Line in 2020.

Pictures

BRM driving courses at Shackerstone.