On Tuesday 25th October 2005, my friend Mike and I were allocated to the Su251-86 which, with a coach and two bogie wagons, was to head south-east to Chernivtsi, about 75 km distant. As I mentioned in Part 1, Su 251-86 is normally based at Chernivtsi and the Ukranian crew were also stationed at Chernivtsi.

Su class background

This locomotive was probably the most 'English' looking of the steam locomotives we saw, although it retains plenty of 'Russian' features. The design was derived from Sormovo Works 'S' class of 1910 via the 1915 'Sv' class from Kolomna Works, re-designed by Kolomna Works in 1925 as the 'Su' class. It became the standard passenger engine for long-distance and suburban work in Russia and over 2,500 were built in four different variants. It was 6-coupled with carrying wheels fore and aft to produce a 2-6-2 (Whyte's) wheel arrangement (although the Russians invariably counted axles, calling it a 1-3-1). With an axle load just over 18 tons, it had good route availability.

The coupled wheels were 1850mm (6'1") diameter. The Russians didn't go in for the small variations of wheel diameter between classes which rather afflicted British designers and the later FDp20 (first built 1932) and P36 (first built 1950) retained the same wheel diameter.

Although elsewhere the vogue was for 4-wheel leading bogies on fast passenger locomotives, for some reason, Russian designers were never keen on the idea and used a 2-wheel leading truck until the 'P36' design of 1950.

English locomotive designers indulged in all sorts of fancy profiles for their chimneys - J. G. Robinson said "The chimney is to a locomotive like a hat to a man - the finishing touch" but the utilitarian designers further east were usually content with a simple tapered 'stovepipe'.

The boiler appears to have two domes but the rear one is a 'Sand Dome' to hold dry sand for application to the rails to improve traction.

A substantial cab is provided, lined with wooden panelling. A prominent feature is a glazed 'skylight' on the cab roof. Access to the cab from the ground is via proper inclined 'stairs' provided with handrails (a distinct improvement on the meagre vertical steps of British designs). The front wall of the cab has doors either side to give access to the footframing and. in common with most Russian steam locomotives, substantial railings are provided around the outside edge of the foot-framing (rather than a single handrail fixed to the boiler, as in British practice).

The class were originally designed for a maximum speed of 115 km/h but the preserved locomotive had been given a much lower limit (40 km/h, I think).

Su 251-86 at Kolomiya Depot.

Su 251-86 at Kolomiya Depot.

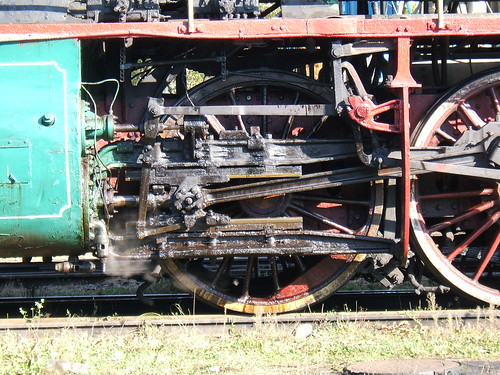

The Su class, like the majority of Russian designs, has two outside cylinders (575mm by 700mm) with piston valves driven by Walschaerts Valve Gear.

Su 251-86: Left hand motion detail.

Su 251-86: Left hand motion detail.

My friend Mike tries out the driver's seat. Russian railways adopt right-hand running on double track, with signals set on the right and locomotives are right hand drive.

The picture below shows the boiler backhead. The general appearance of disrepair was a little worrying but the locomotive operated as required the week that we were there.

The 'skylight' in the roof is visible at the top of the picture. There is a Steam Manifold mounted on top of the firebox, provided with a number of red T-handled shut-off cocks. The two large copper pipes at either end of the Manifold supply steam to the two backhead-mounted injectors. The gland for the regulator rod is in the normal position, on the centre line of the boiler, near the top of the green-painted cladding. However, rather than attaching the regulator handle directly to the regulator rod, a link connects the rod to a short regulator handle mounted lower down and to the right, so as to be more accessible to the driver. The regulator handle works in a notched quadrant and a catch on the regulator handle allows it to be latched in the desired position. There is one gauge glass, mounted to the left of the regulator gland. As a back-up, there are three 'Try-cocks' to the right of the regulator gland. The dual, sliding firedoors are near the bottom of the picture. Each heavy, cast firedoor is suspended on two greased wheels running on the track above the firehole.

Su 251-86: Detail of boiler backhead.

All the locomotives we saw in Ukraine, including the Su 251-86, had large, 8-wheel tenders carried on two bogies, with a fairly simple 'tender cab' at the front, matching the locomotive cab. On the tender sidesheeting, next to the cab and just above the tender underframe, the darker rectangle is the door to a compartment for storing oil bottles and oil feeders.

Su 251-86 at Kolomiya Depot, showing the bogie tender.

Su 251-86 at Kolomiya Depot, showing the bogie tender.

On the road

Despite the engine's battered appearance, the Chernivtsi crew were clearly proud of it, and I quickly grew to like it. We set off on the single line to Chernivtsi, taking it in turns to drive and assist the fireman. We stopped at an intermediate station and the crew took the opportunity to apply more oil.

Su 251-86: My friend Mike oiling the leading truck en route to Chernivtsi under the watchful eye of the Ukranian driver. The oil feeder in use is much larger than that typically used in Britain.

Su 251-86: My friend Mike oiling the leading truck en route to Chernivtsi under the watchful eye of the Ukranian driver. The oil feeder in use is much larger than that typically used in Britain.

As we approached our destination, it became clear that Chernivtsi was a fairly major city - I think the population was around 240,000 at the time. There is a Wikipedia article here. On arrival at Chernivtsi, we were routed into one of a number of sidings leaving the platforms and the impressive station building on our right.

I think we were offered the opportunity to explore the town but Mike and I preferred to stay with the engine. Having uncoupled our short train and left it in the sidings, the engine was signalled to carry on ahead to reach the motive power depot. After about one kilometre, the single-track main line curved away on our right and a few hundred metres further took us to a complex of sidings and the motive power depot.

Chernivtsi Motive Power Depot

Our locomotive was 'parked-up' in the sidings of what is now a diesel depot and we were allowed to wander around the depot (I think the Ukranian crew were taking their lunch break). A turntable served a roundhouse, built of reinforced concrete with brick infill. The capacity of the shed had been reduced by replacing some of the access doors with solid walls. Repairs had been carried out to the remaining wooden access doors on each road leading into the shed. A class TGK2 diesel-hydraulic shunter number 6009 and a smart-looking ChME3 (but with at least one wheelset missing) stood outside the roundhouse.

My friend Mike examines the repairs to the wooden doors of the roundhouse at Chernivtsi.

My friend Mike examines the repairs to the wooden doors of the roundhouse at Chernivtsi.

A smart-looking ChME3 (but with at least one wheelset missing) standing outside the roundhouse at Chernivtsi.

A smart-looking ChME3 (but with at least one wheelset missing) standing outside the roundhouse at Chernivtsi.

We were drawn to two of the massive class 'L' 2-10-0 freight locomotives, L 3535 and L 5141, standing in the open. Starting in 1945, over 4,000 of these popular freight locomotives were built. I'm afraid close inspection found these impressive machines in the same battered state of all the locomotives we'd seen in Ukraine, although not quite as care-worn as nearby 'Er' class 799-82.

'L' class 2-10-0 numbers 3535 (left) and 5141 (right) in store at Chernivtsi.

'L' class 2-10-0 numbers 3535 (left) and 5141 (right) in store at Chernivtsi.

L: 2M62U-0331, R: (in battered condition) 'Er' class 799-82 at Chernivtsi.

L: 2M62U-0331, R: (in battered condition) 'Er' class 799-82 at Chernivtsi.

This trip to Ukraine was the first time I'd seen the Russian pattern of Sanding Tower shown in the picture below. Much later, in 2012, I found even more impressive installations at Ilanskaya (described here).

The Diesel Preparation Sidings at Chernivtsi with a number of Sanding Towers visible.

The Diesel Preparation Sidings at Chernivtsi with a number of Sanding Towers visible.

In addition to the roundhouse, we found what appeared to be workshops served by a number of parallel roads at one end and a lightweight traverser at the other end. It was possibly a wagon workshop but we didn't find any activity around the building.

Near the workshops, we found a narrow gauge 0-8-0 in store. It appeared to be 159-495, 750 m.m. gauge, formerly at Dnepropetrovsk Childrens' Railway in the Ukraine. The Russian 'Gr' class is similar.

Narrow gauge 0-8-0 159-495 at Chernivtsi.

Narrow gauge 0-8-0 159-495 at Chernivtsi.

The Ukranian crew had turned the locomotive on the turntable for the trip back to Kolomiya and decided to take more coal, so a rail-mounted mobile diesel crane with a grab was summoned and used to 'borrow' coal from the tender of L3535 and transfer it to the tender of Su 251-86!

Coaling Su 251-86.

Coaling Su 251-86.

There was clearly some concern about the effectiveness of the steam turbine generator (mounted on top of the firebox) which is used to power the headlamps and other lamps, including cab lighting. A fitter was summoned and he clambered on top of the firebox and made some adjustments. He could be quite clearly heard repeating "Kaput!" but I think we had electricity on the way home.

A fitter at Chernivtsi attempts repairs to the steam turbine generator.

A fitter at Chernivtsi attempts repairs to the steam turbine generator.

The Ukranian crew also emptied char from the smokebox. The complete flat smokebox front is hinged on the left (looking from the front) and, once unbolted, can be swung open for re-tubing and access to the tubeplate. Regular access for char removal is via a smaller dished door, hinged on the right and secured by a number of 'dogs' or clamps which, when tightened, ensure that the smokebox door is airtight. After the char was removed, I closed the door and tightened the 'dogs', using a side spanner.

Removing smokebox char.

The final jobs before our return trip to Kolomiya were to empty the hopper ashpans and oil round.

Su 251-86 with the hopper ashpan doors open. Note the metal scotch placed under the trailing wheel.

Su 251-86 with the hopper ashpan doors open. Note the metal scotch placed under the trailing wheel.

The Journey Home

It was starting to get dark as we set off, at a leisurely pace, back to Kolomiya. I vividly remember driving on this trip with the hypnotic 'clink - clonk' from the motion as we sauntered along through the darkness. For some reason, the beat made me start quietly singing 'The Rhythm of Life' - one of the songs performed by Sammy Davis Junior in the film 'Sweet Charity'. Even with our electric headlight, there wasn't much to see. Every so often, we passed over level crossings, often without barriers, but inevitably with a wooden lamp post carrying a single fluorescent tube throwing pale illumination onto the crossing itself. All too soon, we were back in Kolomiya after an interesting but tiring day. We were happy to leave the Ukraniam crew to complete disposal and we wearily returned to our hotel.

The next day, Mike and I were to drive on the Rakhov line. That's described in Driving Steam in Ukraine (Part 4).

Russian Railway background

At the time of my visit in 2005, I was almost completely ignorant about Russian Railway practice. The book 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' (reference [1] below) is an invaluable primer on Russian steam, diesel and electric traction. In 2011, a river cruise from Moscow to St. Petersburg (described in a series of posts here) gave me tantalising glimpses of railways in Russia. Then, in 2011, I travelled by the 'Golden Eagle' private train from Ulaan Baatar to Moscow (described in a series of posts here).

Book References

[1] 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' by A J Heywood & I D C Button (Frank Stenvalls Forlag) ISBN 0-9525202-0-6.

Photographs:

Ukraine Steam.

Chernovtsy Motive Power Depot, Ukraine.