A quiet moment at Wolverhampton Station: View from platform 3 looking towards Birmingham with the redundant Power Signal Box on the left.

From Wolverhampton to Dudleyport, we were under the care of the West Midlands Signalling Centre at Saltley (control code BW) running under modern LED (light Emitting Diode) colour light signals. Then Birmingham New Street Power Signal Box took over and the signals were mainly Westinghouse 4-aspect colour lights dating from the 1960s. At Birmingham New Street, the 'Pendolino' stopped at platform 1. I discovered how poor the signage and lighting of the recently-rebuilt station is in places. To reach platform 7b for the Nottingham service I had to leave through the automatic ticket barrier and re-enter by another ticket barrier elsewhere, presumably because I took the nearest stairs from the platform marked 'Exit' (as, I think, many passengers might). I've written previously about being generally underwhelmed by the rebuilding here.

Grand Central, Birmingham New Street: One of a number of automatic 'Gate Lines' controlling entry and exit.

The 2-coach 'Class 170' for Nottingham was standing in the south end of platform 7, already well-loaded and we departed on time at 08:17.

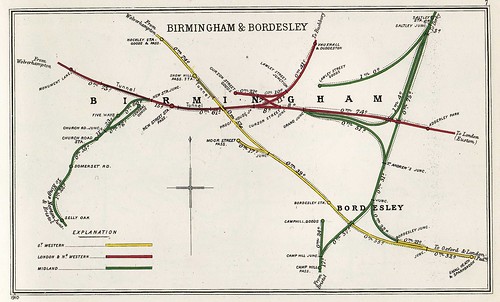

1910 map of lines around Birmingham.

Click here for larger image.

Beyond Proof House Junction, shortly after leaving New Street, we passed from Birmingham New Street Power Signal Box's control to the more-modern West Midlands Signalling Centre's control area 'WP' (Water Orton-Proof House) with modern LED colour light signals. Just before passing the futuristic West Midlands Signalling Centre building, we passed Saltley Power Signal Box (dating from the 1960s) which no longer controls the Birmingham - Derby line although it retains control from Kings Norton to Barnt Green. Saltley Power Signal Box was one of three commissioned in 1969 which used a reed signalling system. The other two installations were Derby and Trent. Derby Power Signal Box currently remains in use but Trent Power Signal Box closed completely in 2013.

Birmingham to Derby: West Midlands Signalling Centre. The LED signal controls exit from the Freightliner Terminal to the Up Washwood Heath Goods Loop and other routes.

At Water Orton, signalling control passed to control area 'WW' (Wichnor-Water Orton), also within the West Midlands Signalling Centre. After a brief stop at Tamworth High Level, where we picked up quite a few passengers, signalling control then transferred to Derby Power Signal Box.

If, like me, you're interested in the operation of the railway itself, modern trains give rather restricted vision of the outside world. Some seats are not even aligned with a window or offer only a narrow, oblique view (certain seats on the 'Class 170' are culprits) and opening windows are a thing of the past. Audible cues can be helpful in interpreting what's going on. For instance, on this journey when the two-tone horn sounded followed after a few seconds by a single short horn, this suggested that the driver had spotted and warned a track worker ahead, the worker had moved to a place of safety and raised his arm in acknowledgement of the approaching train with the final horn confirming that the driver had seen the acknowledgement. On this occasion, the interpretation was confirmed as correct as I spotted the bright orange High-Visibility clothing of the track worker as we sped past the work site.

After a brief station stop at Burton-on-Trent, we accelerated away, passing the intriguingly-named Nemesis Rail depot. Then, there was a prolonged blast from the horn followed by fairly harsh braking. My guess was trespass on the line. We came to a stop just before signal DY187, which was 'green'. We stood for a few minutes, I imagined whilst the driver contacted the Signaller, then we continued to Derby. I couldn't confirm my interpretation of what had happened until we arrived at Nottingham but, yes, I was told the driver had seen "two youths walking down the cess" (the cess is the area immediately adjacent to a running line). The picture below shows the signal where we stopped and the design of this 4-aspect colour light is typical of the 1960s.

Birmingham to Derby: Starting away from an unscheduled stop at DY187 due to trespassers on the line.

The platform carrying the signal head is cantilevered to the right of the main post to improve sighting from a distance. For the benefit of the Signal and Telegraph Lineman, a simple handrail is provided around the platform and there is a permanent access ladder. The main post carries an identification plate with the unique signal number (usually first and last letters of the name, here 'DY' for 'Derby' and a number up to 3 digits long). This signal is on plain line with no diverging routes so the signal is arranged to operate automatically, as track circuits become occupied or cleared by the passage of trains. The white top part of the identification plate with a black horizontal bar indicates that this signal is not controlled by the signaller but is an 'Automatic'. However, a telephone is mounted lower down the main post which communicates with the Signaller. The two grey metal cabinets in the foreground are 'Location Cases' containing the necessary signalling relays, cable termination and power supplies. Two loudspeakers are mounted on the top of the smaller location case. This was the, rather crude, 'Staff Location System' of the period. Mobile phones, as we now understand them, were not available in the 1960s (1973 is accepted as the date of the first call on a Motorola mobile phone). Instead, the signaller could send one of four distinctive tones (one for each of three engineering disciplines plus a continuous tone for 'cancel) to the loudspeakers in an area where staff might be. As you can imagine, in built-up areas at night, use of this facility was not very popular with the neighbours.

In this type of colour light signal, four filamentary lamps are mounted vertically in line. When lit, each produces 'white' light (with a 'yellow' tinge). Colour filters in front of each lamp provide red, yellow or green light which is concentrated by a lens system on each lamp to project an intense beam towards the approaching trains when the lamp is lit. From the bottom, the four lamps produce red, yellow, green and, at the top, a second yellow. Four different 'aspects' or indications are given - red, yellow, green or 'double yellow' (where both yellow lamps are illuminated, but separated by the unlit 'green'aspect so that the driver can distinguish between 'single yellow - "prepare to stop at next signal" and 'double yellow' - "prepare to stop at next-but-one signal").

The most common repair would be 'replace failed lamp' but this type of lamp normally had two filaments. Failure of the main filament was detected by a lamp proving relay measuring the current flowing through the filament. Release of this relay upon failure of the main filament switched in the standby filament to keep the signal lit. The failure would be indicated to the Signaller (who, in the 1960s was still called a 'signalman') allowing the lineman to be alerted. Should the second filament fail or the power supply to the signal be lost, the signal would go 'dark'. In this case, the next signal in the rear would automatically be held at 'red' until relays proved that the failed signal should be showing a 'proceed' indication, in which case the signal in the rear would be allowed to display a 'single yellow' to allow trains to be kept moving whilst the problem was rectified. There's a little more information about this type of signal and the electromechanical relay circuits which typically controlled them here

We arrived at Derby on time, where the driver usually changes ends so as to depart on the Up Nottingham line. I say 'usually' because, on this particular diagram, we had a new driver from Derby to Nottingham.

Railway Clearing House Map: Derby, 1913.

Click here for larger image.

Of course, I remember Derby in steam days with mechanical signalling. At the south end of the platforms, a footbridge crossed the lines to the Works and, sometimes, this would be crowded with 'train spotters'. But my eye was always drawn to the nearby Midland-pattern signal box at London Road Junction.

London Road Junction signal box, Derby (Photo: The Derby Signalling Web Site).

For more about signalling around Derby in that era, see The Derby Signalling Web Site. There's also an article titled SIGNALLING AROUND DERBY STATION on the invaluable site The Signal Box.

Back in the present, my train left Derby station taking the sharp left-hand curve past Derby Power Signal Box, picking up speed on the following straight.

Derby Power Signal Box, commissioned in 1969 and still in use.

On our right was what used to be the Railway Technical Centre. This research facility was created by British Railways in the early 1960s as "the largest railway research complex in the world". I made a few visits on business and it certainly impressed me. But, with rail privatisation in the 1990s, this facility was dismembered with international services company Serco, as Serco Rail Technical Services, taking part of the business and Rail Vehicle Engineering Limited (RVEL) much of the balance, dealing with vehicle modifications and repairs. The American company Loram, best known, perhaps, for their rail grinding machines, took a majority stake in RVEL in September 2014, acquiring the company in 2016. The Network Rail testing trains, hauled by diesel locomotives provided by Direct Rail Services are also based on the site. Unused accommodation is now rented out by RTC Business Park. There's a brief history of the Railway Technical Centre on Wikipedia here. I find this fragmentation very depressing.

Former Railway Technical Centre, now with 'LORAM' signage on the building.

We continued to Trent, a remarkable network of railway junctions which, until the end of 1967, had an interchange station named after the River. I'm afraid I never had an opportunity to study the area in steam days but there's a website here. Since 2013, the somewhat-simplified complex has been controlled from the East Midland Signalling Centre at Nottingham. From the delightfully-named 'Sheet Stores Junction' (nowadays more prosaically usually called Trent West Junction) we took the Up Trent East Curve to Trent East Junctions where we threaded our way to the Down Nottingham.

Railway Clearing House Map: Nottingham, 1913.

Click here for larger image.

We passed through Attenborough and Beeston on double track then there were four reversible running lines into Nottingham with the complication of the Mansfield line joining on our left by a triangular junction. We arrived, on time, in bay platform 5.

Although I'd travelled to Nottingham by train on various occasions in the past, none had provided the opportunity for photography or exploration so I'd arranged my journey so as to allow a little time to make a brief survey of the station before going on to 'Lionsmeet'.

Nottingham station: View from platform 3 showing (middle) a DMU ready to depart eastwards from platform 4 and (right) the DMU on which I arrived ready to leave westwards from bay platform 5.

You'll not be surprised to learn that I didn't approve of most of the modern architectural features the recent station rebuilding has introduced but I am quite enthusiastic about the surviving 1904 buildings in red brick with terracotta detailing.

Nottingham station: The quality of the red brick with terracotta detailing from the 1904 rebuilding is still impressive.

The concourse features glazed terracotta called 'faience' which is impressive (even if a touch excessive).

Nottingham station: Glazed terracotta ('faience') in the concourse.

I hope to give more details in a future post but, in the meantime, there's a Wikipedia history of the station here.

Books with route or track diagrams

[ 1] 'Pre-Grouping Railway Junction Diagrams 1914', published by Ian Allen (ISBN 0 7110 1256 3).

[ 2] ‘British Railways Layout Plans of the 1950’s - Volume 8: Manchester and Chesterfield to Derby and Trent’ (Signalling Record Society) ISBN: 1 873228 09 0. Derby - Trent.

[ 3] ‘British Railways Layout Plans of the 1950’s - Volume 14: ex-MR lines Whitwell to Glendon Sidings via Nottingham, and branches’ (Signalling Record Society) ISBN 1 873228 19 8. Trent - Nottingham.

[ 4] ‘Railway Track Diagrams Book 4: Midlands & North West’ (TRACKmaps: 4th edition) ISBN 978-0-9549866-7-4 The modern railway.

Related posts on this website

Grand Central and Birmingham New Street Station.

Princes End Electrical Controls (Part 4) 4-aspect signals.

My pictures

West Midland Railways.

Grand Central, Birmingham New Street.

Derby - Birmingham, ex-Midland Railway.

Derby - Nottingham.