skip to main |

skip to sidebar

When I was growing up after World War II, railways in Britain went through major changes. There's a very brief introduction to this period here.

British Rail started to electrify part of the network at 25kV a.c. using Electric Multiple Units (EMU) for generally shorter-distance passenger services but a series of 100 electric locomotives were initially produced in 1965-1966 for haulage of conventional passenger coaching stock and freight trains. Sixty locomotives were built by English Electric at the Vulcan Foundry in Newton-le-Willows and a further forty by British Rail at Doncaster. Originally designated 'AL6', they were re-classified Class 86 in 1968 with the introduction of the 'TOPS' fleet management system.

With the Privatisation of the railway network in 1994, operation of trains and track was split, with trains franchised to a miscellany of Train Operating Companies and the ill-starred Railtrack taking over the network. In January 1997 Virgin Trains acquired the Cross Country and Inter City West Coast franchises which it operated until November 2007. The Virgin CrossCountry franchise had 19 Class 86 locomotives in the fleet with the Virgin livery being applied from 1998. One locomotive-hauled electric service ran from Manchester Piccadilly to Birmingham International and the events described below were in this period. Later, in 2001, Class 220 'Voyager' and Class 221 'Super Voyager' diesel-electric multiple unit trainsets built by Bombardier started to displace the loco-hauled passenger services from Manchester and this changeover was complete by the end of 2002.

Only once have I had a 'hands-on' experience with a Class 86 electric locomotive. It happened like this. A few days before my Class 86 experience, I'd been driver at Peak Rail when we had a private charter for a group of railwaymen. Our motive power at the time was the customary 'Austerity' six-coupled saddle tank. In addition to the catering on the train, it had been arranged that a few of the group would be allowed to have the opportunity to drive under supervision. As far as I could tell, they were all serving or retired locomen. It was interesting to see how the younger drivers, without previous experience of steam traction, were fascinated by the techniques of managing a steam locomotive. It was quite a jolly occasion and I'd enjoyed meeting this group of professionals.

On the day of my own 'hands-on' experience, I intended to travel from Wolverhampton to Birmingham New Street for some long-forgotten but not-very-vital purpose and the first train to Birmingham was a Virgin CrossCountry Manchester to Birmingham service. As the train arrived with a Virgin-liveried Class 86 at the head, I was surprised to see the driver wave at me, so I walked to the leading cab by which time the driver was standing at the open cab door. I was amazed to find it was one of the drivers I'd met on the Peak Rail private charter. He apologised that we hadn't time to talk but explained that his destination was Birmingham International where he'd run round and, a little later, work back to Manchester. I decided to abandon my original plan and instead travel to Birmingham International so that we might have a chat. I jumped aboard the train and for most of the journey pondered the chances that the train I decided to catch was driven by somebody I'd met and that the driver had recognised me standing on the platform as I watched the train arrive.

When the train arrived at platform 2 at Birmingham International, I walked up to the cab and was welcomed inside. My friend explained that, once uncoupled by the resident shunter, he would run round to the north end of the stock and then have a break in the train's buffet car. I offered to meet him at the other end of the train after the run round but, instead, found myself ushered into the driving seat. I was given a rapid course in moving the locomotive. I recognised most of the controls and indications on the driver's desk but found the large six-position Main Controller Handle (Off/Run/Notch Down/Hold/Notch Up/Run) rather odd.

Click for larger view

Arrangement of Class 86 driver's desk (from Proceedings of B.R. Electrification Conference 1960)

Checking that the signal was 'off' for us to proceed, I followed the instructions and the locomotive moved ahead. I was happy with the speed for a shunting move, but my friend instructed me to 'notch up' to a higher speed saying "They don't like us to hang about on the main line carrying out shunting moves". I could see the point. My experience is generally on fairly short run-rounds on preserved lines but Birmingham International is designed with generous proportions and turnouts for quite high speed running. From the time the signalman set the route for us to move away from the train until the time we approached the other end of the train, the Down line remained unavailable for any other movements. We travelled forward about a quarter of a mile before we cleared the turnout which needed to switch to allow us to change direction and run past our coaches on an adjacent platform road. As well as clearing the turnout itself, we needed to move beyond the end of the track circuit protecting the turnout otherwise track circuit occupation would prevent the signalman from setting the route for us. The signalman was miles away from us at Birmingham New Street Power Signal Box and so relied entirely on the local interlocking to safeguard the moves and the remote indications presented to him to interpret the situation. Having successfully stopped in the right place using the 'Straight Air' brake, we then had to 'close the cab' and 'change ends' to the cab at the other end, walking along the passage through the equipment room past a mass of complex control equipment, deafened by the noise of the various blower motors and compressors.

I was placed in the new driving seat and given a series of instructions to 'open the cab', check the signal, get the locomotive moving and 'notch up' to the required speed. As we approached the station, the driver slipped back into the driving seat and I stood nearby, not hidden but clearly not driving. This subterfuge made me think of an unofficial footplate ride many years before on a steam locomotive approaching Crewe (described here) when I learnt that 'There's always somebody at Crewe on the look-out for trouble'. "Maybe Birmingham International too" I thought to myself. As we passed clear of the platform, we changed roles again and I was allowed to bring the locomotive to a stand clear of the signal which, when 'off', would allow us to move onto our train. We changed ends again, having travelled around three-quarters of a mile along the down line from where we first changed ends.

For the final time, I set us in motion but, again, as we approached the platform the driver resumed his seat and finished the move, braking gently and firmly buffering-up to the coaches, allowing the resident shunter to 'hook on' to the waiting train. Having checked that the locomotive was safe to be left the driver invited me to join him in the buffet car for a chat.

The buffet crew were very friendly and, as the driver and I talked, I was plied with various refreshments. After a very agreeable time, I decided I'd not outstay my warm welcome but take the next train back to Birmingham New Street and carry out my original planned leaving the driver to his break before he drove the train back to Manchester. A marvellous, unexpected experience and I was very grateful for the generosity of my driver friend.

I'm sorry, I can't confirm the date or the locomotive involved and there are no photographs. That was, I think, the third electrically-powered locomotive I'd driven (as distinct from diesel-electric power). The first was the Dick Kerr battery shunting locomotive at Manchester Museum of Science and Industry - a very useful machine with control gear similar to early electric trams. The second was not a conventional electric locomotive but a narrow-gauge prototype tram made by Parry People Movers. When in the station, a connection to an electric supply powered an electric motor connected to a large flywheel which absorbed energy by being spun at high speed. This stored energy was then used to drive the tram to the next station, where the flywheel was 'spun-up' again electrically. I'd also spent some time in the cab of Manchester-Sheffield-Wath Class EM2 at Manchester Museum of Science and Industry when all the auxiliaries and pantograph could be exercised and 'driving' practised, without actually moving the locomotive, so I don't count that (but there's a brief description in the post here.

Privately-owned Class 86 electric 86259 'Les Ross' at 'Tyseley 100' in 2008.

Related posts on other websites

British Rail Class 86 (Wikipedia).

British Rail Class 86 Electric Locomotive (rail.co.uk site).

The Life and Times of Locomotive 86259

Related posts on this website

The Modernisation of British Railways

'Black 5' to Birmingham

Class 'EM2' D.C. Electric

[Links added: 22-Dec-2023]

At the end of 2021 the Battlefield Line secured 'Foxcote Manor' at short notice to work the Christmas season trains. My first turn on 'Foxcote Manor' was on 19th December 2021, as described in the post Battlefield Line 'Santa' Trains 2021 (which includes a brief introduction to the 'Manor' class).

Once the programme of 'Santa Specials' was complete there was a short break then a series of 'Mince Pie Specials' was operated, extending to the 3rd January 2022. I was rostered to drive on New Year's Day, with Stephen W. as fireman. I correctly anticipated that we'd still be running with a six coach train, limiting our opportunities for taking water, as explained in my post about my 19th December 2021 turn here. On New Year's Day, we were able to ensure that the tender was full before we moved out of the shed, as evidenced by water overflowing from various locations including the tender water gauge before the hose supply was turned off. Stephen had already set the fire and he was happy to share the oiling-round with me so we spent some time completing the examination and applying oil as required in companiable silence. By the time we'd completed this task, there was sufficient steam to move the locomotive just outside the shed in time to carry out some cleaning.

Until Nationalisation of railways in 1948, Great Britain's lines had been dominated by the 'Big Four' (LMS, GWR, LNER, SR), each with their own system for locomotive running numbers. British Railways integrated these numbers into a single series, generally by adding a 'fifth digit' representing the former owning railway in front of the old number. The Great Western had always used brass nameplates on the cab sides for the locomotive number so, in view of the cost of replacing these, former Great Western locomotives retained their original number. The other railways had normally used numbers painted on the cab sides, so they had to apply a prefix, ultimately a number but, for a time, the LMS used the prefix 'M' before the original number.

'Foxcote Manor' outside the shed at Shackerstone in British Railway's 'Mixed Traffic' livery of black (currently unlined) on New Year's Day 2022 (Battlefield Line)

In addition to the cabside numbers, most locomotives also carried the number at the front. The Great Western had always painted this, using yellow 'shaded' characters, on the front buffer beam, generally with a letter code indicating the 'home shed'. These painted identifications were removed and a cast iron numberplate was mounted on the smokebox door, in line with the other railways.

Motive Power Depots were also renumbered in a British Railways series which was an extension of the former LMS scheme (see Wikipedia article here) and a cast 'shedplate' was added. '84G', carried by 'Foxcote Manor', was Shrewsbury which provided motive power for the major passenger traffic on the Cambrian line.

'Foxcote Manor' outside the shed at Shackerstone showing smokebox door with cast number and cast shedplate

When the signalman opened the box, we shunted across to the train, nice and early, 'hooked-on' and started steam heating the stock. There was a little drizzle and we discussed rigging the 'storm sheet' between engine and tender but agreed not to do this unless the weather deteriorated. In fact, the drizzle stopped, the weather improved and it became a pleasant day although not very warm.

I'd assumed that the 1st of January would be a quiet day with people recovering from a late night on New Year's Eve but, in fact, there were already plenty of visitors around by the time we came off shed and it was very pleasant to be carrying good passenger numbers throughout the day. The 'normal' 4-round trip service was being operated, with departures from Shackerstone at 11:00, 12:30, 14:00 and 15:30. The usual timings applied, allowing a line speed of 25 m.p.h. except where lower limits were mandated.

We set off on our first run a little late, waiting for passengers to board, collected the single line staff at the signal box and proceeded up the bank to Barton Lane Bridge at the prescribed 10 mph. Beyond the bridge, we could gently accelerate to Line Speed. Tender first, the 3,500 gallon tender we were propelling allowed a much better view of the line than with the larger 4,000 gallon tender of a 'Hall' but it was also noticeable how exposed to wind the crew are travelling in this direction.

Market Bosworth station had re-opened to passengers and it was gratifying to see people alighting and boarding there. Shenton also had plenty of people around but Stephen and I were kept busy running round our train ready for our return journey.

On receipt of the 'right away' from the Guard, we made a gentle departure, complying with the 5 mph speed restriction because of the embankment 'slip' until clear of Ambion Lane bridge. Speed was then allowed to rise up Shenton Bank using full first valve on the regulator and adjusting the cut-off for best economy. The picture below shows the fireman's view looking ahead on Shenton Bank, with the Belpaire firebox cladding sheets pierced by four sunken washout plugs in a horizontal line with the domed cover of a fifth washout plug visible on the top front corner.

Fireman's view ahead on Shenton Bank (Photo: D. Mould)

We made our scheduled stop at Market Bosworth then continued to Shackerstone, where our arrival on platform 2 was watched (and photographed) by vistors on both platforms and the footpath leading to the engine shed.

'Foxcote Manor' arriving in platform 2 at Shackerstone on a Mince Pie Special (Photo: D. Mould)

With six coaches, we had to stop with the engine fouling the foot crossing to platform 1 so we quickly uncoupled and moved forward, allowing passengers to use the crossing. Once the passengers had finished crossing, we moved tender-first over the crossing into platform 1 where we stopped, to allow visitors the chance to photograph the engine.

'Foxcote Manor' poses for visitors outside the Victorian Tea Room at Shackerstone.

The cabside view below of 'Foxcote Manor' shows the 'Collett Cab' which was deeper (front to back) than Churchward's design. Both designs have a recess in the rear of the cab sheet, allowing the crew to lean out for better visibility but Collett's deeper cab had space for a brass-framed side window. The rearward extension of the cab roof is helpful, too (although less so when running tender first). The cab is narrow enough to accomodate a rather precarious footway outside, allowing enginemen to access the main foot-framing directly from the cab, assisted by an 'L'-shaped handrail provided near the side window. The cab side carries the painted route code circle in blue with the letter 'D' inscribed representing power classification (equivalent to British Rail 5 Mixed Traffic). The iconic GWR cast brass numberplate '7822' is mounted lower down the cab side.

Cabside view of 'Foxcote Manor' on Mince Pie Specials (Photo: D. Mould)

After the pause for photographs, we completed the run round, ready for the second round trip. The day continued very agreeably with our second, third and final round trips. Our engine steamed well and gave us no concerns, although it was clear that she'd put in significant mileage since the last heavy repair. Steve, in particular, had a tiring day with the firing and hooking on and off at each end of the line but we were both quite tired by the time disposal was complete.

A few days after my 'Mince Pie Special' driving turn, issue 289 of the magazine 'Heritage Railway' appeared with a picture of 'Foxcote Manor' at Shackerstone on the cover. Inside, a 6-page colour spread in their series 'PRESERVED LINE PROFILE' provided a good introduction to the Battlefield Line.

Heritage Railway Cover (Issue 289 Jan 21-Feb 18, 2022)

'Manor' Musings

This was my second turn on 'Foxcote Manor' during her short visit before returning to normal duties on the West Somerset Railway. Although sister engine 'Dinmore Manor' had previously visited the Battlefield Line, I hadn't had a driving opportunity so my previous experience of 'Manors' was many years earlier, limited to a delightful running-in and demonstration turn with 'Dinmore Manor' when the locomotive emerged from Tyseley Locomotive Works, plus a firing turn on 'Bradley Manor' at the West Somerset Railway. 'Foxcote Manor' had been hired-in at short notice to replace 'Wightwick Hall' which had been used during the 2021 season, so it was natural to compare 'Foxcote Manor' with 'Wightwick Hall'. After all, they're both Great Western 4-6-0 designs with two outside cylinders and, although both classes are credited to Collett, they remain firmly of Churchward lineage. There are technical differences between the classes, best understood by considering the third, intermediate design stage - the 'Grange' class.

Hall and Modified Hall class

The 'Hall' class is effectively a 'Saint' with smaller coupled wheels (six feet diameter rather than the 6 feet 8 and a half inch diameter of the 'Saint') but with the same boiler and cylinders (18-1/2 inch diameter with a 30 inch stroke).

Click for larger view

'Modified Hall' Class from British Locomotive Types 1946 (Railway Publishing Co. Ltd.)

No 'Saint' locomotive was preserved but there is now a reconstructed 'Saint' produced by converting a donor 'Hall' into 'Lady of Legend' by Didcot Railway Centre as described here.

Click for larger view

'Saint' Class from British Locomotive Types 1946 (Railway Publishing Co. Ltd.)

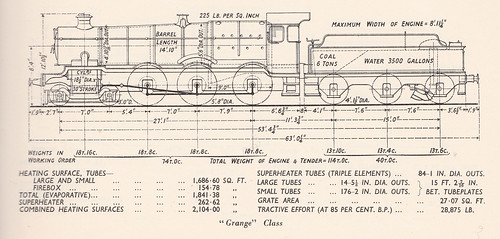

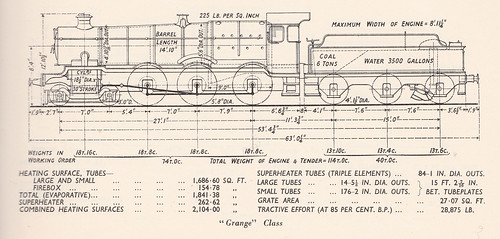

Grange class

Back in 1911, Churchward had introduced the '43XX' class of mixed traffic 'Moguls'. They were well-liked, very successful and with good route availability resulting in over 300 being built. By the mid-1930s, earlier '43XX' were in need of replacement and increasing loads suggested an increase in power was also desirable. Collett decided on a 4-6-0, rather than a 2-6-0, wheel arrangement which became the 'Grange' class, keeping the accountants happy by re-using the 5'8" diameter coupled wheels and motion from withdrawn '43XX'. The 'Grange' is based on a 'Hall' with smaller coupled wheels (5 feet 8 inch diameter rather than the 6 feet of the 'Hall') but with the same boiler and cylinders (18-1/2 inch diameter with a 30 inch stroke). No 'Grange' locomotive was preserved but there is a project nearing completion to reconstruct a 'Grange' (see the website here). The 'Grange' class was very popular with footplate crews. It's often called "the enginemen's engine". It had a particular reputation for being free-steaming (perhaps oddly, as it used the same boiler as the 'Hall) and for pulling-power (whilst it had the same-sized cylinders as the 'Hall', there were some differences in the steam passages and, of course, the smaller coupled wheels gave a tractive effort advantage over the 'Hall'). Although I remember seeing 'Granges' in traffic during my childhood, I'm afraid the technical niceties were rather lost on me then.

Click for larger view

'Grange' Class from British Locomotive Types 1946 (Railway Publishing Co. Ltd.)

Manor class

However, the increased weight of the 'Grange' compared with the '43XX' restricted the new class (like Collett's 'Halls') to 'Red Routes'. So Collett also designed a smaller 4-6-0 design which became the 'Manor' using a new 'lightweight' boiler (Swindon No. 14), the lower axle loading allowing use on 'Blue Routes' in the West Country and Wales. The 'Manor' had slightly smaller cylinders (18 inch diameter rather than the 18-1/2 inch diameter of the 'Grange', but with the same 30 inch stroke) together with other changes.

'Manor' Class from British Locomotive Types 1946 (Railway Publishing Co. Ltd.)

Click for larger view

Related posts on other websites

Foxcote Manor Society.

7800 'Manor' class introduction (The Great Western Archive).

GWR 7800 Class (Wikipedia).

'Betton Grange' 6880.

'Lady of Legend' 2999.

Related posts on this website

Battlefield Line 'Santa' Trains 2021.

All my Battlefield Line posts.

My photograph albums

Where necessary, clicking on an image above will display an 'uncropped' view or, alternately, pictures may be selected, viewed or downloaded, in various sizes, from the albums listed:-

'Foxcote Manor' at the Battlefield Line.

All my Battlefield Line pictures.