Worksplate on 3794 'Cumbria'.

Prior to the normal service of five round trips to Shenton, we had a Gold Footplate Experience booked. These popular courses give the trainee one round trip driving to Shenton and back 'light engine', followed by a second round trip to Shenton with a train attached. Friends and family of the trainee may travel in this train.

A text the night before informed me that Martin Sargent would be fireman for the Gold Footplate Experience but he would not be available all day so it might be necessary to run some of the service trains with the Diesel Multiple Unit.

I 'signed on' in the Staff Room at the station just before 6.30 a.m. - Martin had arrived forty minutes earlier. Having read the 'Notices' displayed in the glass-fronted notice case, I collected a copy of the Operating Notice covering the holiday period. The Operating Notice is issued periodically and lists the speed restrictions currently in effect on the line, important engineering work, the trains to be run day-by-day, special instructions and a list of important telephone numbers.

Preparation

I walked to the Engine Shed and met Martin. Having completed all the initial checks on the locomotive, he was about to 'light-up'. I hunted for oil feeders, oil bottles and oil to allow me to 'oil round' and carry out the all-important daily examination of the locomotive. I commented to Martin that the 'top' of the engine (all the painted areas above the foot-framing) looked very clean, shining in the artificial lighting in the shed. Sadly, the same was not true of the 'bottom' (wheels, motion and the area between the frames) and my overalls were soon liberally coated in oil and dirt.

Raising steam, oiling and the 'daily exam', together with cleaning as time permits comprise 'Preparation', which is an important part of footplate work. In the old days, footplatemen acquired the necessary technical knowledge by attending Mutual Improvement Classes, briefly described here. There's a list here of articles in this blog which describe working on the footplate or cover topics dealt with at Mutual Improvement Classes.

An earlier article here describes the preparation of a similar 'Austerity' tank at Peak Rail and the post 'Operation: Market Bosworth' - On the Footplate describes the preparation of 'Cumbria' at Shackerstone on a previous occasion.

Gold Footplate Experience

We came 'Off Shed' at about 8.40 a.m. with a full tank of water (using the hose inside the shed) and picked up our Trainee Driver. I briefly described the main driving controls (regulator, reverser, steam brake) and outlined the use of the whistle and cylinder drain cocks. The signalman had set the crossover road and cleared the signals for us so we set off slowly, with the Trainee Driver at the controls, collecting the necessary single line token from the signalman as we passed the signal box. Most Trainees have not driven a steam locomotive before, so the rush of sensations as their actions starts the locomotive usually makes quite an impression! The experience is very different from driving a car - 'Cumbria' on its own, when full of coal and water, weighs around 50 tons.

The driving was complicated by my insistence that we economise on steam by 'linking-up' the motion on the road, the need to comply with the various speed restrictions and whistle at the mandatory 'Whistle' boards but we made good progress to Shenton and stopped in the platform briefly. Having hauled the reverser into full forward gear, we set off back to Shackerstone, with the Trainee Driver now gaining more confidence. On our arrival, I surrendered the Single Line Token to the signalman.

Before coupling onto the train for the second part of the Gold Footplate Experience, we replenished the saddle tank and I described the vacuum braking system that we would use when hauling the train, where the Driver's Vacuum Brake Valve would control the vacuum brake cylinders throughout the four-coach train. Our Trainee's family boarded the train and, on receiving the 'Right Away' from the Guard, we set off again, this time with the Trainee having a better idea of the route he was driving over and the way in which the the locomotive responded to the controls. With four coaches attached, the total train weight was around 200 tons and, of course, we were using the vacuum brake for stopping. Our Trainee did very well and, after Martin had uncoupled 'Cumbria' from its train at Shenton, the Trainee shunted the engine to the opposite end of the train ready for the return leg.

We were soon on the move again and made our way back to Shackerstone, where our Trainee stopped the train correctly in platform 2. His family gathered round to congratulate him and Mark H. asked me, as Supervising Driver, to present the documentation testifying to his Experience.

The Weather

Although the previous few days had been warm and sunny, the weather forecast for the Bank Holiday (naturally) was not too good and the morning was dry but rather overcast. In fact, this type of 'slightly dubious' weather can be helpful to the railway in encouraging people to decide to visit an attraction where the train itself will protect them from any rain and there are things to do under cover (at its three stations, the Battlefield Line boasts three cafes, four shops and a railway museum). Really hot, settled weather encourages people to pursue outdoor activities like the beach and may reduce visitor numbers at the railway. That certainly seemed to be the case on Bank Holiday Monday and both Martin and I were surprised at how many people had arrived for the first departure at 11.15 a.m. Although Martin had arranged to be elsewhere during the day, he decided that he would definitely fire the first round trip, so that we provided the expected steam service to our passengers.

The Service Trains

Having said 'Goodbye' to our Gold Footplate Experience trainee, I ran 'Cumbria' round its train, pausing at the water column where Martin and I filled the saddle tank again, then Martin attached us to the train and I created vacuum in the train pipe. After all the passengers had sorted themselves out, we left somewhat late.

In the earlier post here (also referred to in 'Preparation' above) I listed the various speed restrictions in force some months ago and I'm afraid these remain in place, except that the length of track affected by the 'slack' at Headley's Crossing has been reduced. I discussed some of the issues regarding methods of driving 'Cumbria' in the section "Notes on driving 'Cumbria'" in the earlier post Sunday at Shackerstone. One of the attractions of working on the footplate is that, whilst an understanding of the principles involved in steam locomotives is essential, the final success (or otherwise) is dependent upon the willingness of both driver and fireman to closely observe, every day, the result produced by each action and modify those actions, where required. It's been said it's both a Science and an Art.

After a couple of turns of the coupled wheels in 'Full Gear', I set the reverser to what I call 'Linked-Up a Bit More' (explained in 'Sunday at Shackerstone', mentioned above) and controlled the speed on the regulator until we were clear of the 10 m.p.h. 'slack' at Barton Lane overbridge, when I pushed the regulator handle over to 'Full First Valve'.

Locomotive Regulators

A couple of earlier posts talk about regulators used on steam locomotives - Locomotive Regulators (part 1) and Locomotive Regulators (part 2).

On most locomotives fitted with a slide-valve regulator with two valves, when the regulator handle is at 'Full First Valve' it feels as if there's a definite 'stop', although the quadrant extends further. This occurs when the pilot valve has completed its travel and further movement of the handle requires the much-larger main valve to move. The steam pressure holding the larger main valve against the port face means that a greater effort is required to start to move it. The picture below (looking down on the regulator valve assembly from above) illustrates the difference in size between First Valve and Main Valve on the vertical slide valve regulator of an 'Austerity' Tank Locomotive. Of course, you can only see this when the dome cover has been removed and the steam dome inspection manhole has been unbolted - the picture was only possible during repairs following a regulator failure in service which is described in the post The Best Laid Schemes ....

View of regulator valve, showing 'U' shaped pilot valve in front of the broad main valve.

View of regulator valve, showing 'U' shaped pilot valve in front of the broad main valve.

The First Service Train

Because we were running late, apart from the various speed restrictions and our booked stops at Market Bosworth, most of the running was performed with the reverser set to 'Linked-Up a Bit More' and the regulator at 'Full First Valve', producing a satisfying roar from the chimney top when running at line speed. I personally don't often use main valve - on the types of railways I work on with moderate gradients and modest loads, it's rarely needed and, if your fireman has not had a chance to prepare for the greatly-increased demand for steam when on main valve, the boiler can become 'winded' and lose pressure. However, on a couple of occasions when I pushed the regulator handle over to 'Full First Valve', the handle didn't stop part way across the quadrant, as expected, but moved further, suggesting that the main valve had started to move. 'Cumbria' has suffered a long-term problem in getting the regulator to shut properly also indicating that the main valve is not always, as it should, moving independently of the pilot valve.

Steam Lock

It's possible for a steam locomotive to become 'steam locked', where steam becomes 'trapped' in the steam chest when the locomotive is stationary and the steam pressure on the valve makes the reverser very hard to move. This can occur if the main valve remains partly open with the regulator handle in the fully closed position and open drain cocks are unable to adequately vent the system. Potentially, any locomotive with unbalanced slide valves can develop this difficulty. Even the 1838 locomotive 'Lion', the first locomotive I ever drove, occasionally 'steam locked'. The remedy was to wait and eventually the cylinder drain locks would reduce the pressure sufficiently for the reverser to be moved. I've discussed driving 'Lion' in the post Driving 'Lion' (although I didn't mention 'steam locking').

'Cumbria' has an unfortunate tendency to 'steam lock', making adjustments to the reverser very heavy. This is particularly problematic after 'easing up' to slacken the coupling when 'unhooking' from a train. The effect is similar to a regulator being 'gagged in second valve' described in the post on regulators 'Locomotive Regulators (part 1)' mentioned above. When 'steam lock' occured on 'Cumbria', the technique which worked on 'Lion' offered no solution and brute force on the reverser seemed to be called for. However, I found a slightly-altered driving method reduced, but didn't eliminate, the chance of a 'steam lock' occurring by ensuring that each time the regulator was closed, it was done smartly and from 'Full First Valve' position. The cylinder drain cocks were also opened whilst the train was still in motion, in the hope that any residual steam would be discharged before the locomotive came to a stand.

Later Service Trains

As the engine became thoroughly 'warmed through' both steaming and running seemed to improve and both Martin and I agreed that we were enjoying ourselves. The only tedious part of the proceedings was the need to take on water each time we ran round at Shackerstone - 'Cumbria' does seem rather thirsty. Martin decided that, rather than leaving early as he'd arranged, he'd carry on firing for at least one more trip.

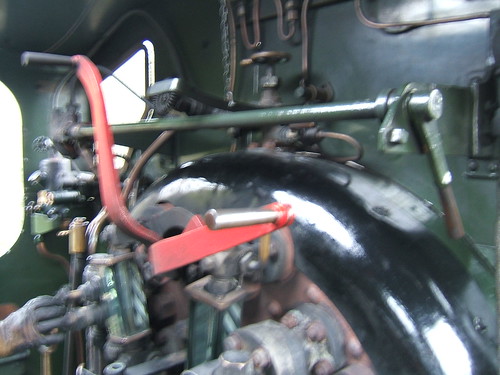

The driving controls of 'Austerity' tank locomotive 'Sapper' illustrated here are similar to 'Cumbria'.

In fact, we ran four of the five booked service trains with 'Cumbria'. By this time, the dry but overcast weather of the morning had deteriorated into drizzle which eventually turned into continuous rain, prompting me to repeat my usual remark "Anyone can work on an engine in good weather - it takes a footplateman to do it in bad weather". We'd agreed that, on completion of the fourth round trip, we'd put 'Cumbria' on shed and, whilst Martin carried out disposal of the steam locomotive, I would 'fire-up' the Diesel Multiple Unit for the final service train, where passenger numbers are usually lower.

The Diesel Multiple Unit

The Battlefield Line is fortunate in being home to the Diesel Multiple Units owned by Ritchie Marcus. There's an introduction to Diesel Multiple Units in the post here.

At Shackerstone, there's a single-unit 'Bubble Car' (55005, built by Gloucester Railway Carriage and Wagon Company in 1958) and a 2-car set (51131 built Derby in 1958 paired with 51321 built Birmingham Railway Carriage and Wagon in 1960). When necessary, all three cars can be worked in multiple. In 2016, the single-unit could sometimes be seen working with half of the 2-car set whilst the other half of the set was undergoing renovation but all three cars are now back in traffic after significant work by Ritchie and his team.

Lined up on the Railcar Siding I found the 'Bubble Car' and, next to the outlet signal having been used the previous day, the 2-car set. Having been on a steam locomotive all day, I had to "switch hats" and think about a completely different form of traction. This was the similar to sudden change that countless steam footplatemen were faced with during British Rail's Modernisation Programme in the 1950s and 1960s. Some men adapted well and saw the advantages of a better working environment: others couldn't face mastering a new technology and were devastated by the loss of a way of life.

On a DMU, the driving controls are neatly laid out on the desk in front of the driver.

I can sympathise with both reactions but, as the rain sluiced down, the prospect of sitting on a padded seat in a enclosed cab for the last round trip certainly appealed. I set about carrying out the check of levels and daily exam - much simpler than on a steam locomotive but equally vital.

Having started all four engines from the ground, I was able to climb inside as I waited for the compressors to produce sufficient air pressure to be able to operate the electro-pneumatic controls and carry out the start-up checks, including the all-important test of the Driver's Supervisory Device (DSD), more popularly known as the "dead man's handle", in each cab. Since Diesel Multiple Units are single-manned, the DSD is needed to stop a train in the case of incapacitation of the driver.

The Guard had joined me from the main train and unlocked all the doors. The signalman had 'set the road' and cleared the signal so I gently drifted down to Platform 1 to pick up our passengers. I'm afraid the changing over from steam to diesel made us late away but, with 600 horse power available for a 2-coach train, we could accelerate rapidly although subject to the same speed limits as the steam train. I'd already noted from the previous day's report sheet that one engine had shut down 'on the road' so I wasn't worried when the same engine shut down on me. A push of the engine start button in the cab restarted it and no further problem occurred. We stopped at Market Bosworth for a few passengers, but the station buildings were already locked. At Shenton, I changed ends. That involves switching the electric marker lights at what was the front to red and taking the Master Key, 'Spoon' handle, Brake Handle and Train Staff to what will become the leading cab. I often manage to forget one of these items, resulting in an extra trip back to the other cab.

By the time we set off on our return journey, the rain had started to ease but I was still glad of the air-operated windscreen wiper. However, rain or shine, I normally keep the cab window open so that I can listen to the noises from the train. I'm reluctant to become too isolated in the cab, reliant on the instrumentation provided. The Guard had determined that there were no passengers to alight at Market Bosworth so, as I approached the platform, he buzzed me to omit the station stop. Once through the speed restriction in the station, I was able to accelerate to line speed and we were soon back at Shackerstone. While the Guard closed windows and locked the passenger doors, I changed ends then I took the train back to where I'd found it, shut it down and completed the daily report sheet.

Although tired after a shift of more than 11 hours, I'd had an excellent day and the contrast between the two types of traction we'd used was interesting.

My pictures

Where necessary, clicking on an image above will display an 'uncropped' view. Although I didn't get a chance to take pictures on the day, the albums below (from which pictures may be selected, viewed or downloaded, in various sizes) show the motive power we used:-

'Cumbria'.

2-car DMU.