skip to main |

skip to sidebar

When I was writing the post Railways around Preston, I was reminded that there remained one passenger line in the area I'd not travelled on - the Preston to Ormskirk line. This had been a double track main line with services from Liverpool Exchange to Preston and East Lancashire but it is now withered to a single line from Farington Curve Junction near Preston which terminates at Ormskirk, where there is now an 'end on' connection with the Merseyrail network which operates an electric train service to Liverpool.

Incidentally, there's another 'end on' connection between Merseyrail and Network Rail at Kirkby, on what was the Liverpool - Wigan Line of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. I'd tried out this service, just over a year earlier, as described in the post Day Trip to Southport and Liverpool (Part 2). Perhaps the service from Liverpool Lime Street via St. Helens to Wigan North Western on former LNWR lines is more convenient.

Keen to try out the Ormskirk line before it changes any more, I decided on a trip on Saturday 17th October 2015. The first part of my journey, to Preston, is described in the post Wolverhampton to Preston by rail.

On arrival at Preston, I made my way to platform 1 for the 10:08 to Ormskirk. After a couple of minutes, a single-car Class 153 rumbled into platform 1 from the south.

The Ormskirk train arriving at platform 1.

The Ormskirk train arriving at platform 1.

I was quite surprised at how many people were waiting to board the service. The Driver and Guard changed ends and we departed on time, taking the Up Slow to Farington Curve Junction where the double-track East Lancs Line diverges to the right. We initially joined the East Lancs Line but, within 100 yards, we had taken the crossover and the right hand route leading to the single line to Ormskirk.

After a little less than three miles, we slowed for the approach to Midge Hall Level Crossing, which is provided with manual controlled barriers and skirts. A 2-aspect colour light signal of 1970's vintage beckoned us over the crossing but we paused momentarily to pick up the single line electric token to Rufford. I only glimpsed the British Rail pattern signal box provided in 1972 as part of the Preston area resignalling. At the time, double track was retained between Farington Curve Junction and Midge Hall (presumably worked 'Track Circuit Block') but it has since been singled (so I assume 'Tokenless Block' is now used).

Midge Hall Level Crossing.

Midge Hall Level Crossing.

About two and a half miles beyond Midge Hall, our first station stop was at Croston, which features a handsome stone former station building now in private hands. A station noticeboard displayed a poster for Community Rail Lancashire. The Preston - Ormskirk line is one of two lines in the West of Lancashire Community Rail Partnership (the other is the Wigan - Southport line, which I described briefly in the post Day Trip to Southport and Liverpool (Part 1)). A second poster at Croston featured the history of the station.

The former station building at Croston.

The former station building at Croston.

We were passing across a flat plain, brightly illuminated by a low sun, with the hills of East Lancashire in the background. It was all very attractive and pastoral whilst the 'click-clack' of the rail joints was a reminder of how little fishplated track remains. The driver frequently sounded the horn as we approached minor level crossings with user-worked gates.

"It was all very attractive and pastoral".

"It was all very attractive and pastoral".

We crossed over the River Douglas and stopped at Rufford station. This retains a level crossing with manually controlled barriers and skirts, a passing loop, two platforms and an inelegant 'Portacabin' signal box. The waiting facilities look like converted garden sheds, painted white - one step up from 'bus shelters', I suppose. The Midge Hall - Rufford electric token was surrendered and the Rufford - Ormskirk one train token issued.

Just over two miles beyond Rufford, we passed over the double-track Wigan - Southport line mentioned above. Originally, the (then double track) Ormskirk line made a triangular connection with the Wigan - Southport line just south of Burscough Bridge station on the Southport line. We stopped at Burscough Junction a shadow of its former self, where only the old Up platform is now used.

Burscough Junction, showing disused Down platform.

Burscough Junction, showing disused Down platform.

A final run of about two and a half miles took us to Ormskirk - the end of the line. Originally, there were two through platforms, two bays, an 80-lever Lancashire and Yorkshire pattern signal box, extensive goods sidings and a four-road locomotive shed with a 50 foot turntable. At least the attractive station building on the down side has been tastefully restored. Presumably, this is due to Merseyrail, who have a policy of staffed stations, well-lit with toilets (the 35-year old Class 507 and 508/1 electric multiple units operated are without toilets). The inside of the station building was brightly-lit, warm, provided with reasonable seating and a modern ticket office facing the door. The platform side of the building has a partly-glazed canopy of modern design but apparently retaining the original cast columns. The effect is quite pleasing. I was reminded of similar restorations of platform canopies at Irlam (described in the post Irlam Station Launch) and Llandrindod Wells (described in the post A Trip to South Wales (Part 1)).

Ormskirk station building from the road side.

Ormskirk station building from the road side.

Ormskirk station building from the platform side.

Ormskirk station building from the platform side.

The passenger information displays indicated a wait of less than ten minutes before the next Liverpool train. Meanwhile, the Class 153 I'd arrived on left on its return journey to Preston.

The Class 153 prepares to return to Preston.

The Class 153 prepares to return to Preston.

The Merseyrail trains arrive at the same platform as the Preston trains, but further along. Just outside the station, the single platform line splits into separate Up and Down lines. My train arrived and we were soon counting off the stops - Aughton Park, Town Green, Maghull, Old Roan and Aintree. I was surprised at how many passengers boarded for only one or two stops before getting off, but throughout we seemed to be carrying a reasonable load in our 3-coach set. Beyond Aintree, I was back on a previously-travelled line (briefly described here). My train terminated at Liverpool Central and I made my way down to the Wirral Line and took a train to James Street.

From here a brisk walk took me to the Museum of Liverpool to check up on their 'star exhibit', the locomotive 'Lion' (there's more than you need to know about 'Lion' and its supporters club OLCO on my blog here). In the Atrium, a special performance of traditional Irish music was in progress, performed by young people and adults from the Wirral who have learned to play traditional Irish music from scratch. I thought they were excellent. There's a short video here. When you've seen the video, the Back Button will return you to this post.

Museum of Liverpool: A special performance of traditional Irish music in the Atrium.

Museum of Liverpool: A special performance of traditional Irish music in the Atrium.

Next, I hurried to Pierhead to book on the ferry departing at noon for Seacombe and Birkenhead Woodside. It's a trip I've done many times but I never tire of it. (I've previously written about taking the ferry, for instance here, here, and here. I commented to the booking clerk that they seemed very busy and he agreed. 'Snowdrop' (still, I'm afraid, with the 'razzle-dazzle' paint job) docked and discharged a heavy load of passengers, before filling up again with the waiting crowd. I positioned myself, as usual, on the open deck towards the bow but I'd forgotten just how breezy it can be. As 'Snowdrop' crossed the Mersey diagonally, I watched an MSC container ship leave Liverpool docks, fussed by two tugs. 'MSC' always makes me think of the 'Manchester Ship Canal' but, in fact, the shipping line is the Mediterranean Shipping Company (their English website is here). With the container ship turned seawards, the two tugs were freed to make their way upstream. Meanwhile, the rather odd superstructure of an approaching ship resolved itself as the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company's futuristic-looking wave-piercing catamaran 'Manannan', heading for her berth next to Pierhead. There's an interesting article about 'Manannan' on Wikipedia here.

As the MSC container ship turns seawards the two tugs have completed their job whilst 'Manannan' makes her way upstream.

As the MSC container ship turns seawards the two tugs have completed their job whilst 'Manannan' makes her way upstream.

We docked at Seacombe with quite a tide running and it took a minute or two to moor and put the gangway in position. Once we'd disembarked departing passengers and boarded 'joiners', we were off again on the short leg to Birkenhead Woodside.

Ferry 'Snowdrop' berthing at Seacombe Landing Stage.

I disembarked when we arrived at Birkenhead Woodside and walked towards Hamilton Square Merseyrail station, pausing to take in the view of Liverpool (rather spoiled by the remarkable clutter of street furniture in the foreground).

I decided I'd time to take the train to the next station on the West Kirby Line - Conway Park. It's a modern station constructed in a 'box' open to the air. A quick look around outside sufficed, then I returned to the platform to catch a train back to Liverpool.

Conway Park station looking towards West Kirby.

Conway Park station looking towards West Kirby.

After our stop at Hamilton Square, we passed under the Mersey quite effortlessly but I always think of the men who constructed this remarkable tunnel and the tough breed of enginemen who ran steam trains through the tunnel for the first new years prior to electrification. There's a post called Early Days of the Mersey Railway. With still a few minutes in hand, I stayed on the train around the 'Liverpool Loop', getting off at Liverpool Central. I treated myself to a portion of chips which I consumed whilst walking to Liverpool Lime Street.

I was in good time to catch the London Midland service to Wolverhampton where I was able to catch the last bus on a Saturday to my village (at five past four, would you believe?). I'd had an interesting trip and, as usual, returned home fairly tired.

Former Railway Signalling between Preston and Liverpool

Signal boxes on the main line from Preston to Farington Curve Junction are listed in the post Railways around Preston. The signal boxes which dealt with West Lancashire line traffic between Farington Curve Junction and Liverpool Exchange are detailed in the John Swift plans (Book reference [1] below) and are listed below:-

Moss Lane Junction

Midge Hall (21 lever L&Y Tappet)

Littlewood Tile Siding (15 lever)

Croston

Rufford (21 lever)

Burscough Jn. North (20 lever)

Burscough Jn. South (50 lever)

Burscough Jn.

Burscough Abbey

Ormskirk (80 lever)

Aughton Park

Town Green (25 lever LMS frame)

Maghull (28 lever L&Y)

Aintree Cheshire Lines Jn. (52 lever L&Y Tappet)

Aintree Station Jn. (88 lever L&Y Tappet)

Orrell Park (8 lever R.S. Co 1887)

Walton Jn.

Kirkdale East (48 lever)

Kirkdale West (44 lever)

Sandhills No. 2 (76 lever)

Sandhills No. 1 (145 lever)

Exchange Jn. (60 lever)

Liverpool Exchange No. 1 (136 lever)

Liverpool Exchange No. 2 (168 lever)

Pre-grouping railways in West Lancashire

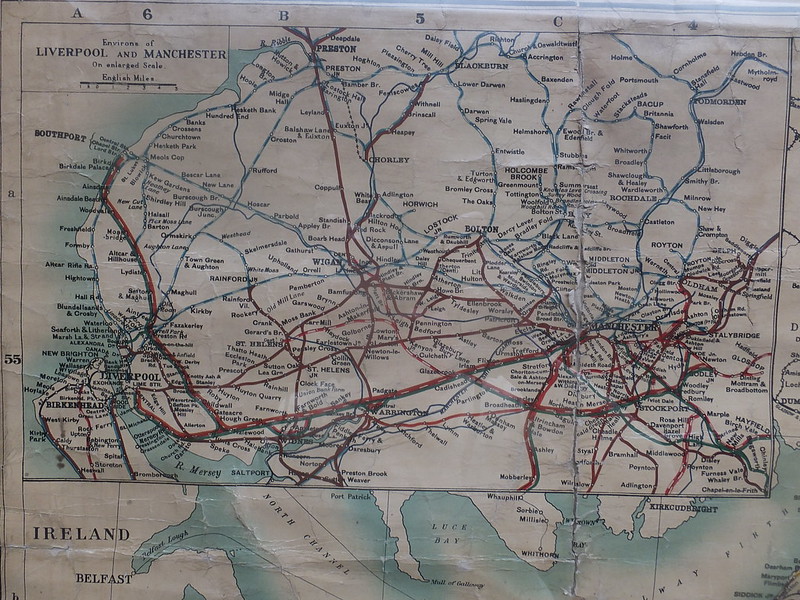

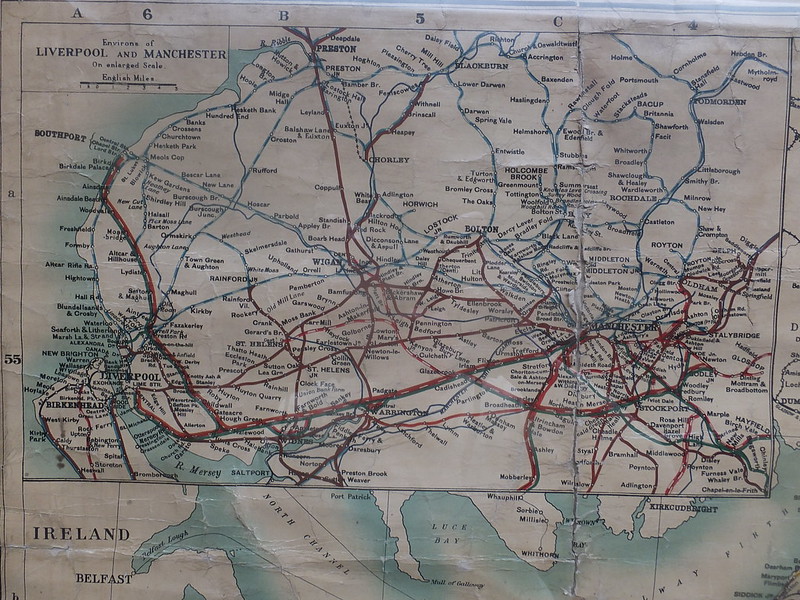

Click for larger view.

Click for larger view.

My journey from Preston to Liverpool was on the former Lancashire and Yorkshire line (blue/white) to Ormskirk where I changed to Merseyrail's Northern Line (originally Lancashire and Yorkshire) to Liverpool Central where I changed to Merseyrail's Wirral Line (originally Mersey Railway) for the short trip to James Street. I then crossed the Mersey by ferry, made a brief trip from Hamilton Square to the modern station at Conway Park (on the Wirral Line) before travelling to Liverpool Central and finally walking to Liverpool Lime Street for my homeward journey. Many of the railways on this map no longer exist.

Books

[1] ‘British Railways Layout Plans of the 1950’s - Volume 5: ex-Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Lines in West Lancashire’ (ISBN: 1 873228 04 X).

[2] ‘Railway Track Diagrams Book: 4 Midlands & North West’, published by TRACKmaps (ISBN 978-0-9549866-7-4).

[3] ‘A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 10 The North West’ by G. O. Holt, revised Gordon Biddle published by David & Charles (ISBN: 0946537 34 8).

[4] ‘The Railways around Preston – An Historical Review’ by Gordon Biddle (Foxline Publishing 1989) ISBN 1 870119-05-3.

Related Posts in this Blog

Day Trip to Southport and Liverpool (Part 1)).

Day Trip to Southport and Liverpool (Part 2).

Railways around Preston.

My pictures

General pictures:

Liverpool.

Museum of Liverpool.

Birkenhead and its Docks.

Railway pictures:

West Midland Railways.

Stafford Area rail.

Crewe Area rail.

Railways around Preston.

Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway in West Lancs.

Merseyrail.

I travelled to Preston by train on Saturday 17th October 2015 so that I could try out the service from Preston to Ormskirk from where Merseyrail has a good service to Liverpool. Most of my journeys by rail start from Wolverhampton which involves a journey by road first from my village to Wolverhampton. For this trip, I took the first bus to Wolverhampton which did not arrive early enough to catch the favoured 07:37 'Virgin' train northwards. Rather than wait at Wolverhampton for the next 'Virgin' service, I took the London Midland Liverpool service to Crewe, stopping at Penkridge and Stafford.

I'm only just getting used to the fact that Wolverhampton Power Box has been abolished and control is now from the West Midlands Signalling Centre at Saltley. Now, the last two signal boxes at Stafford (No. 4 and No. 5) have gone with control transferred to Rugby.

A view of the replacement cantilever signal gantry at the north end of the Station (U&D Goods/U&D Platform) after re-signalling.

There's more change on the way at Norton Bridge. A new flyover junction is being built to eliminate a notorious bottleneck where the line to Stone and Stoke-on-Trent diverges.

I left the London Midland service at Crewe and, having a while to wait, went out of the station to wander around nearby. The multistory offices at Rail House are not elegant but I'm used to them. Over the years, I've attended quite a few meetings with railway staff there. I see that at least part of the building is now occupied by Atos who claim to be 'business technologists' (they've been involved in interviewing claimants as part of the Government's welfare reform programme, attracting a fair bit of criticism).

Rail House, Crewe.

British Transport Police occupy a building opposite provided with a small 'belfry' or perhaps ventilator on the gable roof.

British Transport Police offices, Crewe.

British Transport Police offices, Crewe.

Looking northwards over the parapet of the Nantwich Road bridge, I could see that nature is reclaiming the unused spaces, whilst the 'temporary' signalling centre remains in use.

Nature reclaims North Junction (Signalling Centre left background).

Nature reclaims North Junction (Signalling Centre left background).

I took a couple of pictures of the historic Crewe Arms Hotel.

Crewe Arms Hotel.

Crewe Arms Hotel.

Just round the corner, I recorded the rather bleak railway offices on the east of the station which are linked to the main station footbridge and formerly housed Crewe Control Office.

This building formerly housed Crewe Control Office.

This building formerly housed Crewe Control Office.

The only time I visited was many years ago for a private visit to Crewe Control Office. I was very impressed by the detailed track diagram along one wall with all loops and sidings carefully recorded with their capacity. A series of holes allowed the position of freight trains to be plotted by inserting a peg which held a small card with the train details. A number of desks faced this diagram, each with a telephone concentrator. I was a bit disappointed that passenger trains did not appear on the diagram - I was told they move too quickly. Apart from regulating the traffic and making sure that wagons were available in the right places, the most important aspect of the work was keeping a check on crew hours and making sure that relief crews could be provided as necessary. I wish I'd had longer and I wish I'd photographs but I did take a shot of a similar preserved Control Office Train Board at the Midland Railway Centre, Butterley.

Control Office Train Board preserved at the Midland Railway Centre, Butterley.

Control Office Train Board preserved at the Midland Railway Centre, Butterley.

I made my way back to the station, to look for what was the entrance to the Crewe Control Office from the footbridge. It is transformed! The entrance now leads to 'The Cheshire Lounge' for First Class passengers.

Entrance to 'The Cheshire Lounge'.

Entrance to 'The Cheshire Lounge'.

The sense of luxury is somewhat tempered by a the notice outside instructing customers to press a button and wait for an answer from "a very busy ticket office" after which credentials are checked by holding the appropriate First Class ticket up to a camera for inspection.

I returned to the platform, noticing the stock for 'The Northern Belle' stabled on the adjacent line which is now the Up & Down Loop (but will forever remain No.2 Down Through to me). My Edinburgh-bound 'Pendolino' arrived a few minutes late and we made good time to Warrington Bank Quay. We started to accelerate away from the station stop but, before long, the brakes came on quite hard and brought us to a stand short of Winwick Junction. I could see no obvious reason for the stop and no announcement was made but after a couple of minutes we re-started and reached Wigan North Western without further incident. A final spurt took us to Preston where we arrived still a few minutes late.

My railway pictures

West Midland Railways.

Stafford Area rail.

Crewe Area rail.

Introduction

My first taste of the railways around Preston was on trips to Blackpool by excursion train. I've described one trip I made in 1957 in the post Halfex to Blackpool. I was impressed - multiple running lines, large LNWR-style signal boxes and signal gantries with many dolls, some still sporting LNWR lower quadrant arms. Once I started work, I didn't find the same opportunities to take this sort of trip, particularly after I started working for myself in 1966.

But in the late 1960s, following an initial visit to Preston area by light aircraft chartered by my client (described in the post My First Flight), we secured a contract to supply digital selective call equipment for Lancashire Constabulary. This involved making a number of trips to Preston by train.

Later, in connection with the West Coast Mail Line Electrification Project, a new Power Signal Box controlling the Preston area was commissioned in 1972/1973. My firm supplied certain telecommunications equipment for this project (there's a short post about the development phase here) so, once again, I made a number of trips to Preston by train.

Since then, I've made various trips to or through Preston by both road or rail.

Preston station in 2011: View from the station approach looking south. Left train shed is over platforms 7/6, central train shed is over platforms 5/4 and right train shed (with the end heavily rebuilt) is over platforms 3/2.

Preston station in 2011: View from the station approach looking south. Left train shed is over platforms 7/6, central train shed is over platforms 5/4 and right train shed (with the end heavily rebuilt) is over platforms 3/2.

Preston: View from the footbridge looking south showing roof construction, with 'Pendolinos' in platforms 6 and 5.

Preston: View from the footbridge looking south showing roof construction, with 'Pendolinos' in platforms 6 and 5.

Preston: View looking north from platform 2 as an Up 'Pendolino' approaches.

Preston: View looking north from platform 2 as an Up 'Pendolino' approaches.

Preston Station looking south with Bay platforms 4c and 3c in the foreground.

Preston Station looking south with Bay platforms 4c and 3c in the foreground.

History

Preston has a rather complex railway history. The notes below offer a simplified account.

The Preston & Wigan Railway received its Act in 1831 but, failing to attract sufficient financial support, it joined forces with the Wigan Branch Railway to form the North Union Railway. In 1838 its line was opened from Preston to Parkside, near Newton-le-Willows. This gave connections to the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (opened 1830) and the Grand Junction Railway (opened in 1837 and which, at the Birmingham end, linked to the London and Birmingham Railway). This was the start of Britain's railway network.

The next railway in Preston was a more modest affair. The Preston & Longridge Railway (opened 1840) was built mainly to ship stone from Longridge Fell for use in public buildings in Preston and for the construction of new docks in Liverpool. In the post Notes on Liverpool and its Docks I've written a little about the remarkable Jesse Hartley who was responsible for the high quality stonework provided in the expansion of Liverpool's Docks.

Extending north, the Lancaster and Preston Junction opened in 1840 but the North Union Railway initially made life very difficult by hampering through running. In the same year, the Preston & Wyre Railway, which sought to develop the Fylde area and complete a new port at the mouth of the River Wyre, opened its line. It, too, faced difficulties in through running to the North Union and both these lines opened their own, rather cramped, stations in Preston.

The Bolton and Preston Railway opened in 1843, sharing the North Union line for the 5.5 miles from Euxton Junction to Preston and offering a shorter journey from Preston to Manchester than via the North Union to Parkside and then via the Liverpool & Manchester. However, the high toll charged by the North Union for use of the shared line resulted in the North Union taking over the Bolton and Preston Railway the following year.

In 1844, both the Lancaster and Preston Junction and the Preston & Wyre trains were allowed to run into the North Union station. A direct line from Liverpool via Ormskirk to Preston was being promoted at the time, causing the North Union to feel threatened. It sought amalgamation with the Liverpool & Manchester and the Grand Junction, but these negotiations fell through. Instead, in 1846, it jointly leased its lines to the Manchester & Leeds and the Grand Junction, finally being absorbed in 1888 by the respective successors of the lessors the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway and the London & North Western Railway.

In 1846, a joint North Union/Ribble Navigation Company branch was opened to Victoria Quay, involving a gradient of 1 in 29. The branch was extended to the new Preston Dock in 1892.

The Liverpool, Ormskirk & Preston Railway received assent in 1846 but was swiftly taken over by the East Lancashire Railway which had already absorbed the Blackburn & Preston. The East Lancashire Railway had problems with tolls charged for entering Preston from its long-gone connection at Farington particularly since, by this time, the lessors of the North Union were the London & North Western Railway and the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway! The East Lancashire Railway promoted a Bill for its own route to Preston which was opposed by both the North Union and Preston Corporation. The final settlement involved landscaping near the Ribble and a difficult, curving approach to an expanded North Union station which opened in 1850. In 1859, the East Lancashire Railway amalgamated with the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway which built new connections to Farington Curve Junction from the Liverpool Line (in 1891) and from Lostock Hall (in 1908).

By this time, congestion at the main station was causing many problems but it was not until 1880 that a new station was built, with further expansion in 1902.

Meanwhile, the West Lancashire Railway from Southport reached Preston in 1882 with its own terminus on Fishergate Hill. The railway's ambitious plans for the future were not fulfilled and in 1897 the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway took over and constructed a new line to allow Southport trains to use the main station.

Click on image for larger view

1913 Railway Clearing House map of lines in the Preston area.

Signalling

Just before the second world war, two Westinghouse Style 'L' frames had been ordered, one to deal for the north end of the station, one for the south end. The war cancelled the project and most of the manual boxes struggled on until the present Preston Power Box took over in 1972/1973. One of the Style 'L' frames was used in the Euston resignalling but it was replaced quite soon by the Euston Power Box.

Of course, the manual signalling and the LNWR signal boxes which survived until the 1970s delighted me. I can remember standing on the Up main platform one evening waiting for a connection, just feet away from Preston No. 3 box. Every block bell could be heard clearly and I watched with interest every movement made by the signalman. Until Preston Power Signal Box was commissioned, these were the signal boxes on the main line approaching Preston from the south:-

Euxton Junction (84 lever)

Euxton Coal Sidings (20 lever) Closed in 1965

Leyland (30 lever)

Bashalls Sidings Closed in 1965

Farington Junction (90 lever tappet)

Farington Curve Junction (30 lever)

Skew Bridge (36 lever)

Ribble Sidings (50 lever)

Preston No. 1 (162 lever)

Preston No. 1A (30 lever)

Preston No. 2A (69 lever overhead)

Preston No. 3 (38 lever)

Preston No. 4 (184 lever tappet)

Preston No. 5 (126 lever)

These signal boxes are detailed in the John Swift plans (in [2] below):-

There were originally a number of other signal boxes on the various branches shown in the Railway Clearing House diagram above. The Southport - Preston lines were lost some time ago. I remember the sharply-curved East Lancashire line leaving Preston, but that too, was closed in 1972, freeing up valuable development land. Some of the signal boxes which dealt with East Lancashire line traffic are detailed in the John Swift plans (in [1] below):-

Lostock Hall Junction (40 lever)

Lostock Hall Carriage Sidings

Lostock Hall Station

Lostock Hall Engine Shed

Moss Lane Junction

Trains to the East Lancashire line are now routed via the main line to Farington Curve Junction, then crossing over the main lines to reach Bamber Bridge. From Farington Curve Junction, the Liverpool line survives as a 'long siding' as far as Ormskirk where a change to Merseyrail allows passengers to complete their journey to Liverpool.

Preston Power Signal Box, commissioned in 1972/1973.

Preston Power Signal Box, commissioned in 1972/1973.

Related articles on other websites

There's a lot of useful information on the website Preston Station - Past & Present.

Preston station is now managed by Virgin Trains and there are some particulars here.

There are a number of articles on Wikipedia:-

Preston Railway Station.

London and North Western Railway

Preston and Wyre Joint Railway

Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway

East Lancashire Railway 1844–59

Track Diagrams

[1] ‘British Railways Layout Plans of the 1950’s - Volume 5: ex-Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Lines in West Lancashire’ (ISBN: 1 873228 04 X).

[2] ‘British Railways Layout Plans of the 1950’s - Volume 6: West Coast Main Line (Euxton Junction to Mossband) and Branches’ (ISBN: 1 873228 00 7).

[3] ‘Railway Track Diagrams Book: 4 Midlands & North West’, published by TRACKmaps (ISBN 978-0-9549866-7-4).

Books

Not all of these books feature Preston itself, but they all have information regarding lines and traffic flows in the Preston area:-

‘A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 10 The North West’ by G. O. Holt, revised Gordon Biddle published by David & Charles (ISBN: 0946537 34 8).

‘The Railways around Preston – An Historical Review’ by Gordon Biddle (Foxline Publishing 1989) ISBN 1 870119-05-3.

‘Rails to the Lancashire Coast’ by Richard Kirkman and Peter van Zeller, published by Dalesman Books (ISBN: 1 85568 027 0).

‘Railway Stations in the North West’ by Gordon Biddle, published by Dalesman Publishing Co. Ltd. (ISBN: 0 85206 644 9).???

‘Railways of the Fylde’ by Barry McLoughlin, published by Carnegie Publishing,1992 (ISBN 0-948789-84-0).

‘Railways to the Coast’ by Michael H. C. Baker, published by Patrick Stephens (ISBN 1-85260-058-6).???

‘Railways in East Lancashire’ by Martin Bairstow (self-published 1988) ISBN 0 9510302 8 0.

‘Lost Railways of Lancashire’ by Gordon Suggitt, published by Countryside Books (ISBN: 9 781853 068010).

Related Posts in this Blog

Halfex to Blackpool (trip in 1957)

Railways around Blackpool (trip in 2014)

My Pictures

Railways around Preston

My mother was the born traveller. Whilst she managed a number of destinations in Europe, Poland (when part of the USSR: I accompanied her on this trip), Russia (when part of the USSR), the West Indies, Haiti, North America and Taiwan (accompanying me) she still wanted to see more but circumstances did not permit it. In contrast, at first I was much more timid.

In business, I had to travel and I made a number of trips to Europe, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Thailand and India. The trip to India in 1992 illustrated the problems of travel for business. Whilst I was in India for almost seven weeks, I only had two full days off. Of course, there were periods of free time of a few hours, but never enough to do more than see a little more of Delhi. I made good use of those two full days, travelling by train to Agra, with its Red Fort, Taj Mahal and nearby Fatepur Sikri on the one day and flying to Varanasi (formerly Benares) with the River Ganges on the other. There's an introduction to these early, mainly business, trips here.

After my partner, Daemon, passed away in 1999 I decided it was time I saw a little more of the world, before age, infirmity or poverty precluded such jaunts. With the limitations imposed by the earlier business trips in mind, I decided that, to give me the freedom to visit where I wanted, when I wanted, I would have to pay for my own travel. Let me say at once that I'm aware how fortunate I've been in being able to make these trips. There's an introduction to these more recent (and, I hope, continuing trips) here.

The Potala Palace, Lhasa, Tibet.

The Potala Palace, Lhasa, Tibet.

With the advent of inexpensive digital photography, these more recent trips have given rise to quite a number of pictures (of rather variable quality) which you can find on my 'Flickr' site. There's an index of my travel pictures on my 'Flickr' site here or, alternately, you can choose a country from the list below and jump to a list of collections of pictures for that country.

Antarctic Peninsula: here (trips in 2007 and 2016)

Arctic: here

Argentina: here

Armenia: here

Australia (including Tasmania): here

Australia: (Thursday Island): here

Austria: here

Azerbaijan: here

Bali (Indonesia): here

Bhutan: here

Botswana: here

Brazil: here

Burma

2008 (1st trip): here

2008 (2nd trip): here

2009: here

2010: here

2011: here

2012: here

2013: here

2014: here

2015: here

2016: here

2017 (1st trip): here

2017 (2nd trip): here

2018: here

2019: here

Cambodia: here

Canada: here

Chile: here

China: here

Cuba: here

Dubai (U.A.E.): here

Equador (and Galapagos): here

Egypt: here

Falkland Islands: here

Georgia: here

Germany: here

Hong Kong and Macau: here

India: here

Japan: here

Java (Indonesia): here

Jordan: here

Laos:here

Malaysia (around KL): here

Malta: here

Mexico: here

Mongolia: here

Molucca Isles (Indonesia): here

Namibia: here

Nepal: here

New Zealand: here

Pacific Islands: here

Panama: here

Papua New Guinea: here

Peru: here

Qatar: here

Russia

2011: here

2012: here

Sabah (Malaysia):

2010: here

2015: here

Sarawak (Malaysia): here

Singapore: here

South Africa: here

Sulawesi (Indonesia): here

Taiwan: here

Thailand: here

Tibet (China): here

Turkey: here

Ukraine: here

United Kingdom: here

United Kingdom Overseas Territories:

(South Georgia) here

(St. Helena/Ascension Island) here

(Tristan da Cunha) here

United States of America: here

Vanuatu: here

Vietnam: here

West Papua (Indonesia):

here

Zambia: here

A rather damp Jan at Victoria Falls.

A rather damp Jan at Victoria Falls.

[Updated 16-Jan-2017: 28-Nov-2017: 19-Jun-2018: 9-Oct-2018: 28-Jun-2019: 30-Dec-2020]

The Danish physicist and chemist Oersted (1777-1851) is usually credited with the discovery that electric currents produce magnetic fields (there's a Wikipedia article here). In time, this simple observation led to the technological world of today.

Using an electric current to deflect a magnetised needle gave rise to the Electric Telegraph. Railways were one of the first users of the electric telegraph to allow communication over long distances.

The Single Needle Telegraph was based around two Polarised Galvanometers connected in series, one at the sending end, one at the receiving end. In a polarised galvanometer, an electric current flowing through a coil under the influence of a permanent magnet causes the movement of an armature carrying a pointer. Current in one direction deflects the pointer to the left, current in the opposite direction deflects the pointer to the right. The current is produced by two batteries, connected to the galvanometers by operating one of two switches. One wire is needed from the sending end to the receiving end, plus a return which can be the Earth (or, in the case of a railway, one of the rails).

A Single Needle Telegraph Instrument from which Signalling Block Instruments were derived.

This idea was then adapted to give two adjacent signalmen an indication as to whether the line between them was occupied by a train or not. Provided the controlling signalman operated the switches correctly, the method worked well and the Block Signalling System remains in use today. There's an article describing one type of Block Signalling Instrument here.

L&NWR type 'DN' Absolute Block Instrument.

Another application for Polarised Galvanometers was to confirm to a signalman the state of a semaphore signal which was out of sight, by fixing electric contacts to the signal arm to pass a current of one polarity if the arm was 'on', or opposite polarity if the arm was 'off'. Any position in between 'on' and 'off' passed no current, so that the signalman knew there was a problem. A similar technique was used to prove that the signal lamp was lit. There's an article here.

A polarised galvanometer arranged as a signal repeater for an upper quadrant semaphore distant signal.

The electro-mechanical Relay (often just called a 'Relay') is widely used in control systems in many forms. There's a useful introduction in Wikipedia here. A relay comprises a Coil and a pivoted Armature carrying one or more electrical Contacts. An electric current passed through the Coil produces an electromagnetic field which attracts the Armature. The movement of the Armature operates the Contacts which switch controlled circuits.

By using an electro-mechanical Relay to detect an electric current flowing through the rails, a method of detecting the presence of a train, called a Track Circuit, was developed and perfected in America. To provide the necessary safety, a d.c. current is circulated through the rails to operate a relay when there is no train present. When a train is present, the metal wheels and axle of a train 'shunt' part of this current, so that the relay releases and contacts on the relay can indicate that the track is occupied. Failure of the power supply or wiring cause the relay to release, indicating that the track is occupied, even if there is no train present. This type of design is called 'Fail Safe' and is a fundamental principle of railway signalling.

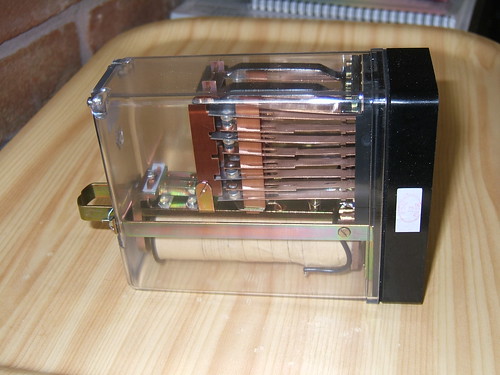

The relay itself must be highly reliable so that it cannot give a false 'Clear' indication, for instance, if contacts become 'welded'. Consequently, railway signalling relays tend to be more elaborate than relays used for less vital tasks. In this country, a common form of railway signalling relay was the 'Shelf Relay' with vertical Coils above a glass-sided chamber mounting the pivoted Armature and the Contacts, as shown in the picture below.

The picture shows a Shelf Relay for use in d.c. track circuits. It has a 9 ohm coil resistance and operates two 'Front' (normally open) and two 'Back' (normally closed) contacts. The rather odd terms used are because, on most designs, the terminals nearest the maintainer when mounted on a shelf (those at the front) connect to normally open contacts whilst those behind (at the back) connect to normally closed contacts. However, the design of the illustrated relay puts the 'Front' contacts at the back, but the terminals are clearly marked 'F' and 'B'.

Neutral Track Relay ('Shelf' type).

Each relay carried a paper test label signed and dated by the tester recording the performance of the relay. Relays were usually 're-certified' every ten years. The two critical parameters for the above relay are recorded on the re-test label:-

Min P.U. 1.47 volts

Max D.A. 0.239 volts

The first (Minimum Pick Up) guarantees that the relay will not 'Pick Up' (operate) until at least 1.47 volts is applied to the coil, guaranteeing that spurious voltages will not operate the relay.

The second (Maximum Drop Away) guarantees that below 0.239 volts applied to the coil, the contacts will have 'Dropped Away' (released), proving that the contacts are not 'sticking'.

The introduction of track circuits gave rise to the need to mount relays in signal boxes or at the lineside and this was often done by providing a wooden cupboard with one or more shelves on which 'Shelf' relays sat.

The picture below shows a number of Shelf Relays wired as necessary.

An elderly installation of shelf relays at Waterloo, prior to de-commissioning.

An elderly installation of shelf relays at Waterloo, prior to de-commissioning.

Simple relays, as described above, will operate the contacts whichever way the current flows through the coil. They were said to be 'neutral'. Some applications require a relay which is polarity-sensitive. This is achieved by incorporating a permanent magnet in the design so that the Armature only moves, operating the electric contacts, on one polarity of current. Current of the opposite polarity produces no movement. This type of relay has many applications in signalling control - for instance, 'proving' that a Block Instrument is displaying 'Line Clear' before allowing the signalman to release an electric lock on a signal lever.

Style 'J' Polarised relay by Westinghouse Brake & Signal Co. Ltd.

Style 'J' Polarised relay by Westinghouse Brake & Signal Co. Ltd.

This relay has two coils, each with 15,200 turns of insulated copper wire giving an electrical resistance of 500 ohms. The two coils are then wired in series, giving an overall coil resistance of 1000 ohms.

Everything is assembled onto the 'top plate' of bakelite (or similar). All external connections are made by connecting wires to the bolt-type terminals fixed to the 'top plate'.

The lower part of the case appears to be cast aluminium. In addition to the Westinghouse label screwed to the top plate, note the British Rail paper test label signed and dated by the tester recording the performance of the relay. The two critical parameters are recorded:-

Min P.U. .0055 Amps

Max D.A. .0033 Amps

The first (Minimum Pick Up) guarantees that the relay will not 'Pick Up' (operate) until 5.5 milliamps are flowing in the coil, guaranteeing that spurious currents will not operate the relay.

The second (Maximum Drop Away) guarantees that below 3.3 milliamps through the coil, the contacts will have 'Dropped Away' (released), proving that the contacts are not 'sticking'.

There are many other designs of relay for particular applications and many types of track circuit beyond the simple d.c. pattern.

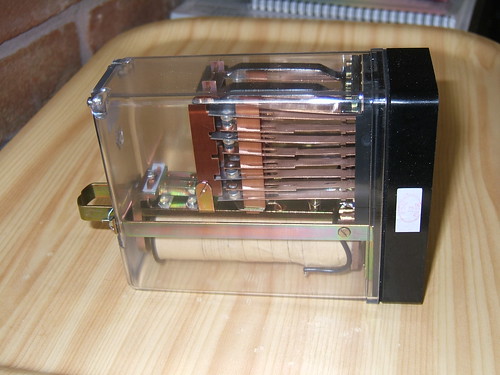

In general, 'Shelf Relays' have been replaced by more modern designs but similar 'fail-safe' principles are incorporated. The 'BR930' is the generic reference for a range of more modern miniaturised plug-in relays still widely used on British and some overseas railways. These are widely known as 'Q' relays as this was the Westinghouse reference. A typical relay is illustrated below.

BR930 plug-in signalling relay made by Mors Smitt UK Ltd.

BR930 plug-in signalling relay made by Mors Smitt UK Ltd.

Even on modern relays, such as the 'BR930' plug-in relay, contacts are still referred to as 'Front' (or 'F') and 'Back' (or 'B'). The reduced relay size allows complex schemes to be assembled using large numbers of relays, as illustrated below.

Relay control system on London Underground used for training purposes.

Overseas, different modern relay designs have emerged but intended to provide the same high integrity as British relays. As an example, the picture below shows an installation in Ukraine using Russian designed equipment.

Signalling relay room, Mikulichin, Ukraine.

Signalling relay room, Mikulichin, Ukraine.

In the last few decades, railway signalling has undergone a revolution. The use of electronics is now widespread and Solid State Interlocking (SSI) is widely adopted and extensive areas are controlled from just a few signalling centres. This development has required the use of complex techniques to emulate the 'fail safe' properties of earlier systems. Except on lightly-used lines mechanical signalling is being eliminated.

Solid State Interlocking equipment in a London Underground signalling training school.

Solid State Interlocking equipment in a London Underground signalling training school.

Books

There are many, many books available on railway signalling. Here's a selection of some, generally older, books I've found interesting which include descriptions of the use of electricity in railway signalling:-

[ 1] ‘Power Railway Signalling’ by H. Raynar Wilson published 1908. (available from various sources as a reprint).

[ 2] ‘The Style L Power Frame’ written and published by J. D. Francis 1989 (ISBN 0 9514636 0 8).

[ 3] ‘Railway Signalling and Communications: Installation and Maintenance’ based on lectures to LNER staff in 1946. Reprinted Peter Kay ISBN 1 899890 24 6.

[ 4] ‘Fifty Years of Railway Signalling’ by O. S. Nock (Institution of Railway Signal Engineers) covering 1912-1962.

[ 5] ‘Two Centuries of Railway Signalling’ by Geoffrey Kitchenside/Alan Williams (Oxford Publishing Co.) ISBN 0 86093 541 8.

[ 6] ‘Railway Signalling: A treatise on the recent practice of British Railways’ edited by O. S. Nock (Adam & Charles Black, 1980) ISBN 0 7136 2067 6.

[ 7] ‘Railway Control Systems’ edited by Maurice Leach (A & C Black 1991) ISBN 0-7136-3420-0.

[ 8] ‘Single Line Control (British Practice’) by P. C. Doswell (Booklet 4, Institution of Railway Signal Engineers 1957).

[ 9] ‘Multiple Aspect Signalling (British Practice)’ by A. Cardani (Booklet 14, Institution of Railway Signal Engineers 1958).

[10] ‘Route Control Systems AEI-GRS’ by A. C. Wesley (Booklet 21, Institution of Railway Signal Engineers 1961).

[11] ‘Route Control Systems:- The S.G.E. 1958 Route Relay Interlocking System’ by J. V. Goldsbrough (Booklet 22, Institution of Railway Signal Engineers 1961).

[12] ‘Level Crossing Protection’ by P. A. Langley (Booklet 25, Institution of Railway Signal Engineers 1961).

Related posts on this website

There's an incomplete series of posts titled 'Railway Signalling in Britain', starting here, with links to subsequent posts.

There's an incomplete series of posts titled 'Spring Vale Electrical Controls', starting here, with links to subsequent posts.

There's yet another incomplete series of posts titled 'Princes End Electrical Controls', starting here, with links to subsequent posts.

There's a brief post here describing Russian-style all-electric signalling at Mikulichin, Ukraine.

Alternately, you can find all my posts on Railway Signalling (mechanical and electrical) here.

My pictures

British Railway Signalling Equipment.

Signalling at Mikulichin, Ukraine.

In my introductory post London Underground and Jan, I described how my interest in the Underground was sparked when my firm became involved in supplying tunnel telephone equipment.

One of the lines I've worked on is the Waterloo and City. At just under a mile and a half in length the Waterloo & City is the shortest of the London Underground railways now operated by Transport for London but it has a lot of interest.

In the post Waterloo Station, London (Part 2) I explained that the London & South Western Railway (L&SWR) which built the main line terminus at Waterloo had an ambition to extend their line eastwards. The Waterloo and City Railway Company was incorporated in 1893 by an Act of Parliament. Although independent from the L&SWR, no less than five of the eight directors of the new line were directors or employees of the L&SWR! Construction of the double-track Waterloo and City Line started in 1894 and it was opened, using electric traction, in 1898. It is 1 mile 46 chains long with two single-bore iron segment tunnels of varying diameter up to 12ft 9in.

The L&SWR operated the Waterloo and City railway from its opening, later purchasing the line outright. At the Grouping, the line passed to the Southern Railway and, upon Nationalisation, to British Railways, ending up part of London Underground in 2004. This history has produced a unique line.

Rolling stock has always been stabled and serviced at a cramped depot below ground level beyond Waterloo station. A siding just north of the Waterloo & City underground station was provided with a lift (built by Armstrong) to the main-line sidings, allowing underground vehicles to be transferred to and from the main lines. The railway generated its own electricity at a power station adjacent to the depot and the Armstrong Lift was also used to receive wagons of coal for the power station. The Armstrong Lift was removed to allow construction of the Waterloo International platforms to serve the Eurostar services, since when the Waterloo & City has been completely isolated from other railways.

The L&SWR started to electrify its suburban main line network from Waterloo in 1915, constructing a large, new power station at Wimbledon to supply the power. The sub-station at Waterloo main line station was arranged to also supply power to the Waterloo & City line.

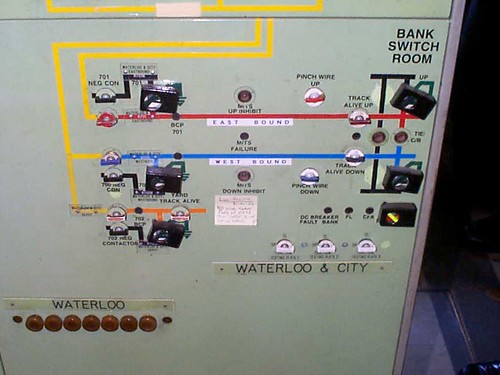

As part of a comprehensive modernisation by the Southern Railway in 1940, the bare copper 'pinch-wires' which form part of the present tunnel telephone system were added. This system allowed the driver to communicate with the signalman at Waterloo (Waterloo & City) and the power supply operator in the main line substation at Waterloo. In 1972, control of the main line substation at Waterloo was transferred to Raynes Park. The original tunnel telephone control panels were left in Waterloo main line substation but the telephone circuits were extended to Raynes Park and a remote reset facility for the tunnel telephones was provided through the electro-mechanical telemetry system for power control.

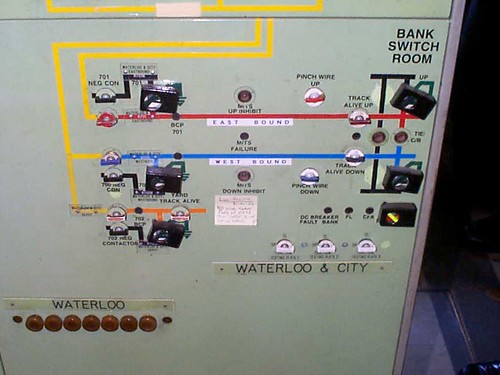

The Electric Control Room at Raynes Park presently controls traction power to the Waterloo & City. This view shows the small part of the large mimic diagram relating to the Waterloo & City.

The Electric Control Room at Raynes Park presently controls traction power to the Waterloo & City. This view shows the small part of the large mimic diagram relating to the Waterloo & City.

At present, traction power is still provided from the Network Rail Main Line Traction Substation via d.c. track feeder cables. There are two tunnel traction sections, one for the Down or Westbound line (section 700), one for the Up or Eastbound line (section 701) line. The Waterloo Depot area, which is not provided with tunnel telephones, forms a third traction section (section 702). Traction sections are fed via high-speed d.c. circuit

breakers, similar to London Underground standard practice. At the remote end of the Up and Down lines, Bank, a Track Paralleling Hut was provided to minimise voltage drop. However, this feature was never commissioned and the railway operates as two single-end fed traction sections.

A new Traction Substation is being completed within Waterloo station near the Waterloo & City line and, once this is commissioned, the Network Rail Main Line Traction Substation will no longer be involved in the operation of the Waterloo & City line.

In 1989 Network South East, who were by then responsible for the line, ordered replacement rolling stock of the LUL Central Line pattern, providing five 4-car sets. Cranes were needed to remove the old rolling stock and deliver the new trains to the depot area, since the Armstrong Lift had been removed as mentioned above. Some civil works were needed to accommodate the new stock and the current collection system was changed from third rail to standard London Underground fourth rail pattern in 1992.

Present Waterloo & City vehicle.

The depot at Waterloo, viewed from the Arrival platform, in 2004.

The depot at Waterloo, viewed from the Arrival platform, in 2004.

Westinghouse replaced the old signalling system in 1992 with a relay interlocking controlled from an 'NX' mosaic panel.

The 'NX' signalling control panel at Waterloo in 2004.

The 'NX' signalling control panel at Waterloo in 2004.

Around 2007, a new Service Control Centre was constructed within Waterloo station. This was provided with a solid-state signalling interlocking system controlled from workstations. The 1992 Westinghouse signal box has been retained as an Emergency Service Control Centre.

The present Service Control Centre at Waterloo.

The present Service Control Centre at Waterloo.

Related information on other websites

Clive's UndergrounD Line Guides form an excellent reference to all of London Underground. The Guide for the Waterloo and City line is here.

There's a Wikipedia article here.

Related posts on this website

All my posts on London Underground can be found here.

Books

In my introductory post London Underground and Jan, there's a list of books about London Underground. From this list, these two are of particular relevance to the Waterloo and City Line:-

[ 1] 'The Waterloo & City Railway' (a very detailed history running to over 460 pages).

[ 2] ‘Railways of Waterloo’ (covers both the Waterloo & City and the main line station).

For a track diagram with other information, refer to another book included on the list in the introductory post here:-

[13] 'Railway Track Diagrams Book 5: Southern and TfL' Third Edition, published by TRACKmaps (ISBN 978-0-9549866-4-3).

Pictures

Waterloo & City.

[Flickr ref updated 3-May-2020]

(Click on map for larger view)

London Underground Map 2015 (Transport for London).

When I was quite young, I was introduced to the London Underground on a visit to London with my parents. I think I was terrified and fascinated in equal parts. Terrified by the speed, the noise and descending into the bowels of the earth to board the trains - fascinated by the frequency of trains and the relative ease of moving underground around London. As an adult, I was happy to utilise the tube but it never had the attraction of steam railways. Even after my firm started supplying special-purpose telephone equipment for railways in various countries, I saw the London Underground network merely as a means of transport, not a potential source of work.

That changed in, I think, 1995 when one of our major customers, who was bidding for a large telecommunications package in connection with the Jubilee Line Extension Project, asked us to quote for the design and supply of Tunnel Telephone equipment. Well, I had a vague idea of what was involved - most people travelling on the Tube notice the pair of bare wires carried on the tunnel wall forming part of the tunnel telephone system. These wires allow the driver to attach a portable telephone in case of emergency. None of the telephone systems we'd produced seemed adaptable to this tunnel telephone application and I thought that the costs of developing suitable equipment from scratch would make any offer we made unattractive. So we declined to quote, explaining our reason to our customer.

However, a few months later the customer came back to us, saying they'd really like us to quote, and this time we produced a quotation. Some time later (these things always seem to take an inordinate time to come to fruition - a large quotation we did for Brazil only produced an order after seven years!) we agreed a contract to design and supply the necessary tunnel telephone equipment for the Jubilee Line Extension. I then embarked on a fairly steep learning curve to better understand both the traction supply system on London Underground and the requirements for tunnel telephone systems. As we produced the necessary equipment, I became far more interested in the history and development of the London Underground system. Over the years since, I've worked on tunnel telephone systems for a number of the London Underground lines and, as time permits, I'll add more posts on this unique mass transit system.

Brief Introduction

The London Underground employs a fairly unusual fourth-rail system of electrification. I've written a little about how traction current is distributed in the post London Underground - Traction Power Distribution and there's a short background in the post Fourth Rail Electrification.

Tunnel Telephone systems used on London Underground have two functions - to discharge traction current in an emergency and allow the driver to talk to the Line Control Centre (now generally called the 'Service Control Centre'). The tunnel wires allow a driver to open the cab window and simply 'pinch' the two bare wires together (the bare tunnel wires are sometimes referred to as 'pinch wires'). This action automatically discharges the local traction section. Connecting a portable telephone to the exposed wires similarly discharges the traction section, after which a conversation with the control centre is possible. Fixed telephones with a similar function are provided at strategic locations (such as the Headwalls at stations). London Underground now call the Tunnel Telephone system the Emergency Traction Current Discharge System (ETCDS) to better-reflect its principal function. Providing speech with the control centre, in this age of Secure Cab Communication by radio, is the secondary role.

Jubilee Line: Tunnel wires mounted on cast iron tunnel lining at the junction of two adjacent Tunnel Telephone sections.

Clive's UndergrounD Line Guides form an excellent reference to all of London Underground.

For track diagrams of London Underground, refer to 'Railway Track Diagrams Book 5: Southern and TfL' Third Edition, published by TRACKmaps (ISBN 978-0-9549866-4-3).

Books

Here's a list of some of the books I've acquired dealing with London Underground:-

[ 1] 'The Waterloo & City Railway' by John C. Gillham (The Oakwood Press) ISBN 0 85361 544 6.

[ 2] ‘Railways of Waterloo’ by J. N. Faulkner (Ian Allen Publishing) ISBN 0 7110 2237 2.

[ 3] ‘London’s Local Railways’ by Alan A Jackson (David and Charles) ISBN 0-7153-7479-6.

[ 4] ‘Steam to Silver – An illustrated history of London Transport railway surface rolling stock’ by J. Graeme Bruce (London Transport) published 1970.

[ 5] ‘Inside Underground Railways’ by Alan A. Jackson (Ian Allen Ltd.) published 1964.

[ 6] ‘The London Underground – A diagrammatic history’ by Douglas Rose (Douglas Rose) 3rd edition ISBN 0 9507101 5 6.

[ 7] ‘Underground Train Overhaul – The Story of Acton Works’ by J. Graeme Bruce/Piers Connor (Capital Transport Publishing) ISBN 1 85414 134 1.

[ 8] ‘The Northern Line – An illustrated history’ by Mike Horne/Bob Bayman (Capital Transport Publishing) 2nd edition 1999 ISBN 1 85414 208 9.

[ 9] ‘The Story of London’s Underground’ (London Transport) revised edition 1966.

[10] ‘British Electric Trains’ by H. W. A. Linecar (Ian Allen) 2nd edition 1949.

[11] ‘Handling London’s Underground Traffic’ by J. P. Thomas (London Underground) published 1928.

[12] ‘The London Underground Tube Stock’ by J. Graeme Bruce (Ian Allen Ltd.) ISBN 0 7110 1707 7.

[13] 'Railway Track Diagrams Book 5: Southern and TfL' Third Edition, published by TRACKmaps (ISBN 978-0-9549866-4-3).

[14] ‘London Underground Guide 2015’ by Jason Cross (Train Crazy Publishing 2015) ISBN 978-1-907648-10-6.

Related posts on this website

All my posts on London Underground can be found here.

My pictures

My coverage of London Underground lines is very patchy and quality is generally rather poor, I'm afraid. All these albums are shown here.

[Book {14} added to book list 11-Apr-2021]

Jerome K. Jerome, best known as a humourist and writer, was born in Walsall in 1859. His most famous work 'Three Men in a Boat' was published in 1889.

Jerome K. Jerome in the 1890s (Photo: National

Media Museum @ Flickr Commons).

Jerome (whose middle name was Klapka) was given the Freedom of Walsall in 1926 (there's black-and-white film of the event here) and died the following year. Wikipedia has a useful biography here. For more information, go to the website of the The Jerome K Jerome Society.

Although I've known 'Three Men in a Boat' since childhood, I was only recently reminded that the book includes a description of taking the train from Waterloo during the period when the haphazard growth of the station had made it a laughing stock. Jerome's description is below:-

We got to Waterloo at eleven, and asked where the eleven-five started from. Of course nobody knew; nobody at Waterloo ever does know where a train is going to start from, or where a train when is does start is going to, or anything about it. The porter who took our things thought it would go from number two platform, while another porter, with whom he discussed the question, had heard a rumour that it would go from number one. The stationmaster, on the other hand, was convinced it would start from the local.

To put an end to the matter we went upstairs and asked the traffic superintendent, and he told us that he had just met a man who said he had seen it at number three platform, but the authorities thre said that they rather thought that train was the Southampton express, or else the Windsor loop. But they were sure it wasn't the Kingston train, though why they were so sure it wasn't they couldn't say.

Then our porter said the thought it must be on the high-level platform; said he thought he knew the train. So we went to the high-level platform and saw the engine-driver, and asked him if he was going to Kingston. He said he couldn't say for certain of course, but that he rather thought that it was. Anyhow, if he wasn't the 11.5 for Kingston, he said he was pretty confident he was the 9.32 for Virginia Water, or the 10 A.M. express for the Isle of Wight, or somewhere in that direction, and we should all know when we got there. We slipped half-a-crown into his hand, and begged him to be the 11.5 for Kingston.

'Nobody will ever know, on this line,' we said 'what you are and where you're going. You know the way, you slip off quietly and go to Kingston.'

'Well, I don't know, gents,' replied the noble fellow, 'but I suppose some train's got to go to Kingston; and I'll do it. Gimme the half-crown.'

Thus we got to Kingston by the London and South-Western Railway.

We learnt afterwards that the train we had come by was really the Exeter mail, and that they had spent hours at Waterloo looking for it, and nobody knew what had become of it.

In 1899 the London and South-Western Railway finally decided to rebuild the station (perhaps the gentle ribbing in 'Three Men and a Boat' played a part), although the work was not completed until 1922. There's a short description of the rebuilding of Waterloo Station here.

In 1956 'Three Men in a Boat' was made into a film which is described here. In 1975 the book was turned into a film for television, briefly described here. The television version can be watched on You Tube here.

The Ormskirk train arriving at platform 1.

The Ormskirk train arriving at platform 1.

Midge Hall Level Crossing.

Midge Hall Level Crossing.

The former station building at Croston.

The former station building at Croston.

"It was all very attractive and pastoral".

"It was all very attractive and pastoral".

Burscough Junction, showing disused Down platform.

Burscough Junction, showing disused Down platform.

Ormskirk station building from the road side.

Ormskirk station building from the road side.

Ormskirk station building from the platform side.

Ormskirk station building from the platform side.

The Class 153 prepares to return to Preston.

The Class 153 prepares to return to Preston.

Museum of Liverpool: A special performance of traditional Irish music in the Atrium.

Museum of Liverpool: A special performance of traditional Irish music in the Atrium.

As the MSC container ship turns seawards the two tugs have completed their job whilst 'Manannan' makes her way upstream.

As the MSC container ship turns seawards the two tugs have completed their job whilst 'Manannan' makes her way upstream.

Conway Park station looking towards West Kirby.

Conway Park station looking towards West Kirby.

Click for larger view.

Click for larger view.