Hoi An by night.

The restorative properties of a hot bath and a simple meal in the hotel are amazing. Having initially given up the idea of going out yesterday evening, I changed my mind and walked around the town before going to bed. There's always a conflict between getting the experiences and writing about them before the details fade. I've uploaded Saturday's pictures but here's just a short version of "What Jan did".

Events of Saturday, 2nd February 2013

The ancient 'Japanese Bridge' in Hoi An.

My guide Than and I started at 8.00 a.m. with a walking tour of Hoi An. It's a charming place and World Heritage 'inscribed' (the posh folks at UNESCO don't just 'list' these places). I hadn't realised quite how dedicated to tourism the east coast of Vietnam had become - it's not to far from both Japan and Australia - but I still enjoyed my brief visit. Our walking tour was finished by 10.0 o'clock in the morning and then we set off by car along the coast road re-tracing our route back to Da Nang.

The caves at Marble Mountain.

On the way, we stopped at Marble Mountain, a massive outcrop of rock rearing up from the plain. An elevator lifted us up the mountain to a series of paths connecting various religious monuments and a large cave system (which rather reminded me of Batu Caves in Malaysia - my pictures of Batu Caves are here). As the name suggests, marble is extracted from the mountain and, at the base of the mountain, there are a number of marble carving workshops and showrooms.

I saw a little more of the modern city of Da Nang where two large road bridges are under construction both, I believe, by American architects. I found the cable-stayed bridge impressive but the other, supported by a series of bright yellow arches each made from a cluster of five tubes and dubbed 'the Dragon River Bridge', I thought ugly. We visited the interesting museum of Cham temple stone carving.

Examples of intricate Cham temple stone carving in the museum at Da Nang.

Then, we took the road over the mountains towards Hue. There is now a road tunnel which by-passes the mountain road but the views from the mountain road are stunning. Lorries carrying livestock or tankers of petrol still must use the mountain road. We stopped at a coffee shop commanding impressive views of the sea both looking south and looking north. Of course, Than knew the family who run the place. They were having a sort of informal lunch party to celebrate the New Year and insisted I join in the alfresco meal. They were so kind, I was sorry when we set off again.

Jan joins the family who run the mountain coffee shop in a celebratory lunch.

We were close to the single-line railway for a lot of the time, so I was trying to study that. I got a few 'drive by' shots on the way but couldn't do more until the evening.

I stayed at the Hotel Saigon Morin in Hue. It was opened in 1901 so, as you can guess, it's my kind of place.

The Hotel Saigon Morin in Hue.

I had a simple meal in the hotel and then went out on foot, eventually ending up at the railway station. I'd been advised that I should be able to purchase a platform ticket to look around the station but nobody seemed to understand the concept and they keep passengers in the waiting room until there's a train to board.To understand the signalling and control, I explored the streets at both ends of the station to try and get near the railway. By the time I'd done that, I was quite exhausted so I returned to the hotel on a motor bike taxi, which was actually very comfortable and great fun.

Provided we don't suffer any more technical setbacks, I'll tell you more when I can.

Photographs

Hoi An.

Marble Mountain, Da Nang

Around Da Nang.

Over the Mountains to Hu

Railways in Vietnam.

Hotel Saigon Morin in Hue.

[Revised 25-Feb-2013]

Saturday, 2 February 2013

Exploring Hoi An and to Hue by Road

Friday, 1 February 2013

Leaving England

'Leaving England'? No, not for ever (I hope) but another Far East Trip. After the cold of this winter, a little warmth would be nice.

Events of Thurday, 31st January 2013

I normally try to avoid Heathrow but, this time, Tim from my travel firm recommended the Thai flight from London so that brought me to Terminal 3 at Heathrow at 9.30 a.m. I had to travel to the airport without a passport because my passport, endorsed with suitable visas, did not get to Tim until the previous afternoon so he said he'd meet me at the airport and hand it to me. And, that's what happened.

Well, the attentions of the security staff at Heathrow got the trip off to a poor start (as often happens). They X-rayed my carry-on bag and everything I could with modesty remove, although this time they let me keep my shoes. The rest of me passed the metal detector but they decided the carry-on bag needed a hand search. They had neither the space nor the staff to do this decently. Soon there was a short queue of us waiting for inspection. We couldn’t avoid being spectators as the lady in front of me had the indignity of watching most of the contents of her case, including her spare underwear, laid out on the metal table while the security girl either passed the items as 'fit to travel' or piled them in a series of trays to be X-rayed again. The man behind me was worried the delay might cost him his flight. Eventually, a second security girl appeared but there was no room where we were waiting to do a second search so she led me off across the floor to another line where there was a desk spare. I went through the same treatment (at least my undies were in a plastic bag) then, to add insult to injury, she offered to help me re-pack, which I declined. As I slowly attempted to put things back where I’d originally put them, I could feel another security guy urging me on, as he was looking for a table too. Did I feel safer for all this security? No.

I made my way through the large Duty Free and found the lounge which Thai share with other Star Alliance Members. The disappointment here was that, despite a large number of Apple workstations with free internet, I couldn’t get a reliable connection, although I tried three different workstations. One problem was that they were right-handed workstations, with the mouse physically on the right of the keyboard and I'm left handed. Usually, I can cope by dragging the mouse towards the left (although there’s often insufficient slack in the cable to do the job properly) but in this case the worktop was shiny and white, with an inlaid black disk on the right for the mouse to sit on. The Apple infra-red mouse refused to work at all on a white background. I couldn’t reach across to the black disk on the next workstation to my left, so I ended up finding a folder in my bag with a texture/colour the mouse was happy with. I still experienced erratic performance (possibly network loading) so I pulled out my own Notebook computer and managed to get that to log-on. Sadly, the performance was still so erratic that I gave up and sulked.

They’d told me to allow 30 minutes to get from the lounge to the gate. Although it didn’t take me that long, it was a longer walk than I would have wished and I was quite relieved to clamber into my seat on the aircraft. The A340-600 was alright but not state-of-the-art and slightly careworn. Although the cabin crew were friendly, they didn’t strike me as meeting the standard I used to associate with Thai. Perhaps my judgement was coloured by my earlier experience with security. My seat allocation (18K) was immediately behind a bulkhead, which gives extra space. The only drawback was the T.V. screen was fixed to the bulkhead and a bit too far away, with a narrow angle of view and bad in sunlight. The aisle seat next to me remained empty so I travelled in splendid isolation.

After pushback from the gate, we threaded our way through the complex system of taxiways to reach the take-off runway.

There are a few more pictures around Heathrow taken on this and previous flights here. We were a little late departing from runway 27 Left (I remember when it was 28 Left – magnetic variation of the poles is a remarkable thing). About a dozen aircraft managed to get away before us but then we were soon crossing the Channel and overflying Belgium. Where there were breaks in the cloud, it looked as if the snow was widespread on the Continent. They served quite a reasonable meal and by that time it was dark outside. The entertainment system was ‘video on demand’. I tried ‘The Bourne Legacy’, a bit of ‘Ted’ (quite funny but rude) and ‘The Candidate’ (intermittently funny or rude or both but very predictable). I managed to sleep a little, although the seat only provided an inclined sleeping position which doesn’t suit me too well. A couple of hours before getting to Bangkok, they served a hot breakfast. We arrived around 10.00 p.m. London time, but I’d already switched to local time – about 6.00 a.m. on an overcast but warm (about 23 degrees Celsius) morning.

Events of Friday, 1st February 2013

At Bangkok I transited to another Thai flight – the TG550 to Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon as was). I still have trouble with the signage at Bangkok airport. First, I had to go up one floor from the arrivals level to the departures level. But before you’re allowed out, you and your luggage are processed by security. This time, my hand baggage passed, but they insisted on X-raying my shoes. I was processed by their body scanner – a cubicle with power doors where you stand, feet apart, with arms in an ‘I surrender’ pose. At least the man and women manning the body scanner gave me a smile as they beckoned me out.

As I feared, gate E1a for my flight was a long, long walk. There are a number of moving pavements but it’s still a long way. Right time, I boarded the aircraft along with around 300 passengers, this time an A330 but I don’t know which of the three variants in service with Thai we flew in.

Thai A330 'Watthana Nakhon' ready to leave Bangkok for Vietnam.

This flight was full and I didn’t get a window seat but the flight was only an hour and bit (although we must have taxied for best part of half an hour before we followed a 747 into the sky). They served a very basic lunchbox (this leg and others to follow were Economy) so I was fairly content by the time we arrived at the airport for Ho Chi

Minh City which is often identified simply as 'HCMC' although the airline ticketing code remains 'SGN' for the old French name, Saigon.

As I expected, the airport at Ho Chi Min City seems to have developed since my previous visit (described in the post Far East Tour, 2005). There was very little delay at immigation and my checked bag arrived quickly. Customs formalities comprised X-raying my bags, then I was disgorged into the Arrivals Hall, packed with ‘meeters and greeters’, a few of which held name labels. I wasn’t expecting to be met here as I was booked to transfer onto a Vietnam Airlines domestic flight to Da Nang, but I scanned the signs quickly before going outside. I think the temperature was in the low twenties. The pavement was also thronged. I guessed the direction to walk for the Domestic Terminal (and got it right). Although I had some hours before my flight left, I managed to check in and 'lose' the big bag, then I set off on foot for a little walk. One of the many security guys watching the traffic coming and going was worried to see me wandering around on foot but suggested a visit to ‘The Market’, actually a department store selling many famous names plus some others. He kindly conducted me across the busy junction and the store doorman opened the door for me. I made my way through five floors connected by escalators.

Ho Chi Minh City Airport viewed from the cafe level at the department store.

I spent at least an hour on the top floor which was mainly an eating area surrounded by lots of different cooked food vendors including a 'KFC' - a bit like motorway services in Britain but there must have been at least 15 vendors. I passed the time with a drink whilst taking in the view of all the coming and going road traffic at the Domestic and International Terminals and writing part of this post. Getting back to the domestic terminal on foot was quite tricky with all the traffic but I was too stubborn to accept any of the numerous offers of taxis or motor bike taxis, although I was a bit tempted by the motor bike taxis who even provided a crash helmet for the passenger. I arrived back at the domestic terminal under my own power safely but exhausted. I went through security and did a bit more on the computer, finished reading my Thursday 'Telegraph' or dozed.

We boarded our flight exactly on time, somewhat to my surprise. Again, the flight was full (or it was where I was, in economy). This time, the aircraft was an A341 (this one second hand but Vietnam Airlines are partway through accepting delivery of a small number of brand-new aircraft of this type). The flight to Da Nang took about an hour and we were soon in the Baggage Hall of the new terminal. I didn't have very long to wait for my checked bag and, being a Domestic flight, there were no immigration or customs formalities. There were quite a few 'Meeters and Greeters' in the arrivals hall, but my taxi driver was displaying a board with the name of the tour company and my name so we were soon driving to my hotel for one night in the historic city of Hoi An. Within about an hour, I was checking in at the 'Hoi An Historic Hotel'. I haven't found out yet how they justify the 'Historic' in the hotel's name - there are three wings and they all look pretty modern.

Hoi An Historic Hotel by night.

I was glad to get to my room (third floor and no elevator as they call 'lifts' in this territory) and have a bath. I abandoned my initial idea of exploring the area before it got dark and decided to sort out this post and my photographs. That's when I discovered that my 'preferred pointing device' (a tracker ball) would not work at all. After a half-hearted attempt at a repair, I decided to continue on the computer's touch-pad and buttons (which I don't find as convenient).

Provided we don't suffer any more technical setbacks, I'll tell you more when I can.

Photographs

Photographs taken on the dates given above either form new sets, or have been added to existing sets, as listed below:-

Heathrow Airport.

Bangkok (Suvarnabhumi) Airport.

Ho Chi Min City Airport.

Ho Chi Minh City Shopping Plaza.

Around Da Nang.

Hoi An Historic Hotel.

Hoi An.

[Revised 25-Feb-2013]

Saturday, 26 January 2013

The Battle of Brewood

Brewood Hall in the snow.

With the title's attractive alliteration, this ought to be an event from history. The truth is a little more prosaic.

The forces which regulate British Weather decided that Britain should have a "proper winter" in early 2013 and there was widespread snow on the 18th January and more on subsequent days. There are a few pictures around Brewood Hall here. Needless to say, the country was immediately plunged into chaos with road, rail and air transport dislocated or cancelled and schools closed.

Before the snow disappeared, it was decided that the Brewood Scouts would make use of the garden for a little snowball practice in 'The Battle of Brewood'. The Scouts had visited just over three years previously for a conducted tour of the principal rooms of the Hall and that visit is briefly described in the post Brewood Scouts visit Brewood Hall (with a link to pictures).

On the evening of Friday the 25th January 2013 it was dark and cold when thirteen scouts and two scout leaders arrived but soon snowballs were being lobbed in all directions.

"A hit, a palpable hit!". Geoff, the scout leader is the target.

Once youthful energies were dissipated, everybody came into the kitchen at Brewood Hall for a cup of hot tomato soup with bread.

The 'Group Shot' in the kitchen at Brewood Hall.

Perhaps this hastily-arranged event can be repeated in the future and the name 'The Battle of Brewood' may yet enter the history books. There are a few pictures of the evening in Fun in the Snow.

Monday, 21 January 2013

Yangon Area Railways

Introduction

Yangon Central (shown as a black square on the map below) is an important rail hub. A 30-odd mile long double-track 'Circle Line' serves the city. At Da Nyn Gone (left side of map) the line towards the west diverges. At Mahlwagone (a little to the right of Yangon Central) the double-track route to Bago diverges. At Bago, the main line continues north to Mandalay and a single line to Maylamyine and the south diverges.

Route Map of Yangon Division (from Myanmar Railways)

List of stations on the Circle Line

Stations are listed in a clockwise direction, starting at the northern part of the Circle Line. Burmese words can be Anglicised in various ways, so alternative spellings of at least some of names may be found.

Golf CourseHistory

Kyait Ka Lei

Mingalardon Market

Mingalardon

Wai Bar Gi

North Okkalapa

Pa Ywet Seit Gone

Kyauk Yae Twin

Tadalay

Yaegu

Parami

Kanbe

Bauk Hlaw

Tarmwe

Myittar Nyuni

Mahlwagone (#1)

Pazundaung

YANGON CENTRAL

Pha Yar Lan

Lanmadaw

Pyay Road

Shan Road

Ahlone Road

Pan I Daing (or Pann Hlaing)

Kyee Myin Daing

Hanthawaddy

Hledan

Kamaryut

Thin Myaing

Oakkyin

Thamine

Gyogone

Insein

Ywa Ma

Phi Taw Thar

Phaw Khan

Aung San

Da Nyn Gone (#2)

#1: Before Mahlwagone the line from the north and east converges with the Circle Line.

#2: Beyond Da Nyn Gone the line to the west diverges from the Circle Line to Golf Course.

In the post Railway Signalling in Burma: Part 3 - Control of Trains I quoted a brief description of the signalling arrangements at the main station in the 1930s when the city was called Rangoon:-

The passenger station yard is controlled by three principal signal boxes, two of which have about a hundred levers each, and the third about seventy-five The Western Electric system of train control is installed throughout the Rangoon area and interlocking is very complete. All signal lamps are electrically lit.After the Second World War, the signalling of the whole area around Yangon has been modernised with colour light signals, track circuiting and motor operation of points.

Equipment supplied by Westinghouse Brake and Signal Company

According to [reference 1], in January 1946, an order was placed with Westinghouse Brake and Signal Company for two Style 'L' miniature lever frames for Burma Railways, intended for 'Rangoon' and 'Kemmendine'.

The Rangoon lever frame order called for 143 levers made up of 42 point levers, 76 signal levers, 6 spare levers and 19 spare spaces. The Kemmendine lever frame order called for 47 levers made up of 12 point levers, 28 signal levers, 6 spare levers and 1 spare space. The Yangon miniature lever frame remains in use and is described here. What happened to the other frame remains a puzzle at present.

General view of the Westinghouse Power Frame at Yangon from the front.

General view of the Westinghouse Power Frame at Yangon from the front.

Yangon Central Station

'Rangoon' is now known as 'Yangon' and the Central Station is currently signalled by a fairly elderly system of 2- and 3-aspect colour lights with power operation of points. Controlled signal numbers are prefixed 'R' (for Rangoon).

Typical signals Left: 2-aspect signal R140 Right: 2-aspect signal R141 (with subsidiary aspect R139). The station pilot (DD517) with a raft of vans stands on the Up Goods (also called Shunting Neck East, according to the signal box diagram).

Kyee Myin Daing

'Kemmendine' is now usually known as 'Kyee Myin Daing' and remains controlled from two manual signal boxes, although colour light signals have replaced semaphores on the main line.'

Pazundaung

Pazundaung Station, showing rear of two 3-aspect signals, each with two 'line-of-lights' route indicators.

Pazundaung station is situated on the four-track section to the east of Yangon Central (Up/Down Main and Up/Down Local). It has colour light signals and motor points. Signal numbers in the area are prefixed 'P' and I believe a separate signal panel is situated in the station building (probably like the one I photographed at Da Nyn Gone).

Mahlwagone

Left: Signal M25 (with subsidiary aspect) on the line from Bago. Right: Signal M24 (with line-of-lights route indicator) on the Circle Line.

Mahlwagone is situated near the convergence of the Circle Line with the line from Bago and has colour light signals and motor points. Signal numbers in the area are prefixed 'M'. I'm told this area is now controlled from Mingalardon.

Pa Ywet Seit Gone

View looking north at Pa Ywet Seit Gone (or, as the nameboard shows, Paywet Seik Kone) showing locomotive running round its train prior to returning to Yangon. Note 2-aspect main signal 3RM and subsidiary aspect 33R (normally out, displays two white, one above the other, to authorise 'shunt ahead'.

This station on the Circle Line is remotely controlled but of interest because there are trailing crossovers at each end of the station allowing a locomotive to run round its train. I travelled on an anti-clockwise Circle Line train which used this facility and continued as a clockwise Circle Line train.

Automatic signals

3-aspect Automatic signal A79 between Pa Ywet Seit Gone and Mahlwagone (clockwise). The associated location case can just be seen beyond the signal.

On areas of the Circle Line around Yangon which are not controlled from a signalling panel, there are a number of signals with numbers prefixed 'A' arranged for automatic operation. There are also automatic signals on the four-track section between Mahlwagone and Pazundaung.

Books

[reference 1] 'The Style L Power Frame' written and published by J. D. Francis 1989 (ISBN 0 9514636 0 8).

Wikipedia Links

Yangon Central Railway Station.

List of railway stations in Myanmar

Related posts in this blog

Exploring Yangon's railways.

The Circle Line Revisited (2012).

The Circle Line, Yangon (2008).

Railway Signalling in Burma - Part 2: Colour Light Signals & Motor Points.

All my Myanma Railways posts.

My Pictures

Cab Ride on the Circle Line (2014).

The Circle Line, Yangon (2013).

Circle Line Revisited (2012).

The Circle Line, Yangon, Myanmar (2009).

Burma: Colour Light Signals & Motor Points.

Yangon Central Station.

Railways in Myanmar (2008).

All my Myanma Railways Pictures.

[Revised 4-Jul-2014: Link to Index added 22-Jan-2020]

Thursday, 17 January 2013

Railway Signalling in Burma - Part 3: Control of Trains

Some of the posts referred to below are still in preparation.

Mike's Railway History includes a brief description of Burma's railways in the 1930s which appears to be from one of the contemporary railway magazines. One paragraph describes signalling:-

The standard interlocking used for all single-line crossing stations on important lines is known as the Simplex system, while there are also a few controlled by List and Morse interlocking. In the Rangoon area the lock and block system is installed on the double line, and about forty double-line stations are interlocked on the key and tappet system. Some twenty junctions and important stations have fully-interlocked cabin locking. On most branch lines the stations are not interlocked, facing points being secured by cotters and padlocks, the keys of which are kept in the custody of the station-master on duty.Another paragraph describes the principal station in Rangoon (now Yangon). At the time, this station was called 'Phayre Street':-

The passenger station yard is controlled by three principal signal boxes, two of which have about a hundred levers each, and the third about seventy-five The Western Electric system of train control is installed throughout the Rangoon area and interlocking is very complete. All signal lamps are electrically lit.I haven't traced other references to 'Simplex' interlocking but a Paper by R. C. Rose titled 'A Survey of Indian Signalling' in the 1924 Proceedings of the Institution of Railway Signal Engineers (available online here) seems similar.

Single-line crossing stations

The Indian system for controlling simple passing loops has a Station Master (of high integrity) in charge, with two Pointsmen who can be despatched to hand operated points at each end of the loop to set them as required. But if the pointsmen make errors, trains can arrive on the wrong track, departing trains can 'trail' incorrectly-set points or points can be changed as a train is passing over them.

So, various forms of key-locking apparatus were produced with the aim of giving the Station Master confidence that his instructions had been correctly carried out. The 'Trapped Key' method has two keys for each set of points which can be inserted in a Locking Box between the rails at the toe of the points. A point stretcher passes through the locking box arranged so that if the points are correctly fitted-up in the 'Main' position, the 'Main' key can be extracted from the Locking Box. Actually removing the key locks the points in that position. The other key remains 'trapped' in the Locking Box. Once the 'Main' key is replaced in the Locking Box, the points may be operated.

Similarly, with both keys present, if the points are operated to the 'Loop' position and are correctly fitted-up, the 'Loop' key can be extracted from the Locking Box and, once removed, locks the points in that position. Now, the 'Main' key remains 'trapped' in the Locking Box.

Thus, if the two Pointsmen each present 'Main' Keys to the Station Master, he may be confident that the points are set for the 'Main' at both ends of the loop. If the Station Master receives two 'Loop' keys, a train may be passed over the loop line. In India, a further development allowed splitting home signals to be worked from a ground frame on the platform.

The arrangements I've seen so far in Burma seem to conform to the above description, except that the splitting home signals are locally controlled by the pointsmen with a further 'Trapped Key' locking box being provided in the push rod to the signal arm (see Part 4 - Manual Control of Points and Interlocking for more information).

Detail of EIC Locking Box fitted between the rails on the Loop Points at the south end of Naba station. The Loop Handles on the two lock slides are at opposite ends of the box. The interlocking key is clearly visible on the left of the box.

The picture below shows a partly-dismantled locking box no longer in use and is included to clarify the construction.

Click here for larger version of the above picture.

'Trapped Key' Interlocking is still widely used in industrial safety in the form of Castell Interlocks (introduced by James Harry Castell in 1922 adapting ideas first used on the railways).

Double-line control

The Circle Line in Yangon is double track, as is the line from Mahlwagon to Bago. Other parts of the system are also double-track (and doubling is being extended) but, at present, I've no information on the original arrangements.

The 1930s description quoted above says "The Western Electric system of train control is installed throughout the Rangoon area". This system originated in North America as an electro-mechanical secret party-line selective telephone system where a number of waystation telephones were all connected to the same pair of wires. A series of impulses sent to line from the control station normally selected only one telephone to speak to or hear the control. This secrecy made it a safe method for communicating train movement instructions as they could not be overheard (and misunderstood) by other waystations. In addition to Western Electric exports, the system was licensed by Standard Telephones and Cables in England and they not only exported systems (for instance, to Thailand) but also adapted the system for use as a Signal Post Telephone system in the U.K. For more information on this system, my friend Sam Hallas has produced a comprehensive article Control Telephone Systems.

Any form of telephone system needs telephone wires between the various instruments. Originally, this would be open wires on a system of poles but latterly multicore cables are used. See 'Part 7 - Telecommunications' for more information.

Regarding Rangoon, the 1930s description quoted above reports "The passenger station yard is controlled by three principal signal boxes". In 1946, an order was placed with Westinghouse Brake and Signal in Chippenham for two Style 'L' miniature lever frames. One, intended for Rangoon (now Yangon) had 143 levers, the other, for Kemmendine (now Kyee Myin Daing) had 47 levers. All signals in the Yangon area are currently colour light with power operation of points but, as yet, I've not determined whether the Westinghouse lever frames remain in use. See the post Yangon Area Railway Signalling for more information.

Typical colour light signal in the Yangon area - automatic A711.

The 1930s description quoted above reports "About forty double-line stations are interlocked on the key and tappet system". This is presumably a variant of the 'Trapped Key' system where keys available physically control which signals can be operated. This may be similar to the method of signal release I've found in Burma (see Part 4 - Manual Control of Points and Interlocking for more information).

The 1930s description quoted above reports "Some twenty junctions and important stations have fully-interlocked cabin locking". Bago North and Bago South signal boxes are certainly 'fully interlocked'. See the post Railway Signalling in Burma: Part 5 - Signal Boxes with Interlocking Frames.

Bago South Signal Box on a rainy day.

References

Mike's Railway History

Burma's Railway System.

(This PDF appears on the website of the Old Martinians Association U.K. forwarded by Peter R. Moore. Some of the text also appears on the Mike's Railway History Page but the Peter Moore article includes additional material and a number of more modern photographs showing steam locomotives).

Control Telephone Systems.

[Photograph of part-dismantled locking box added 20-Mar-2013]

Wednesday, 16 January 2013

The End of an Era

1.15 p.m. Stafford-Shrewsbury arriving at Wellington with 'Jubilee' 45699 'Galatea' on Sat 21-Jul-1962 (D. Wynne Jones Collection).

I consider myself lucky to have been growing up as the post-war railways went through the massive changes of the '50s and '60s. After the long period of wartime austerity, the railways, and the country, were run-down but the traditional pride of railwaymen in being involved in a vital national enterprise was still visible. The socialist government nationalised the 'Big Four' railways in 1948 and, of course, opinions varied about the consequences which would follow. Steam was still supreme, the handful of main-line diesel electrics were seen as curiosities and nobody on the railways had yet heard of Doctor Beeching.

B.R. Standard steam locomotives

But when change came, it came quickly. B.R. Standard steam locomotive designs were intended to replace the motive power which had become 'clapped-out' through the pressures of wartime. Riddles' designs were based on sensible principles of simplicity, two outside cylinders with Walschaerts valve gear and rocking grates with hopper ashpans. The 999 new locomotives turned out were intended to be a unifying influence, encouraging loyalty to the new 'British Railways' rather than the old 'Big Four'. This aim was only partly achieved: the new locomotives were thought 'the best thing that had ever happened' or 'not as good as our old engines', depending who you talked to.

Although the B.R. Standard locomotives incorporated modern design features, steam traction still involved a lot of hard, unpleasant physical work which became less acceptable to employees. At the same time, the political wind changed and it was felt that 'dieselisation' was the future.

B.R. Diesel Shunters

English Electric 350 h.p. diesel electric shunter (later Class 08) at Tyseley Railway Museum in 2008. 13029 was the first diesel I was passed to drive and very handy for shunting early in the morning when the 'steamers' were still 'brewing-up'.

The excellent 350 h.p. diesel-electric shunters revolutionised shunting and trip work, with their ability to be rapidly shut down until required and be available for perhaps a week before returning to the depot. There were also various diesel-mechanical types.

B.R. Diesel Multiple Units

Two-car DMU preserved at the Battlefield Line.

The various designs of Diesel Multiple Unit quite successfully replaced steam on local (and not-so-local services). Existing automotive technology was fairly successfully adapted to the railway environment and the ability to operate variable-length trains by coupling units together or splitting them, as required was quite effective. At the time, the new experience of being able to sit behind the driver and share his view ahead was amazing. My post Diesel Multiple Units has links to various sources of information (the British Railways Driver Training Films on YouTube are particularly recommend).

B.R. Main-line Diesels

British Railways and the various British locomotive builders had a fairly steep learning-curve in seeking to develop successful high-power diesel traction. One of the pioneer classes was the 'Peak' and, of course, 'Penyghent' is preserved at Peak Rail. My post D8 'Penyghent' has links to various sources of information on this class but, despite the interest of the more complex control systems, I've not written a great deal about other classes.

B.R. Electrification

'Tyseley 100' featured a preserved 25 kV a.c. locomotive.

Having thrown away a modern 'stud' of steam locomotives in favour of diesel, British Railways then started to electrify. Of course, the Southern Railway had electrified much of their complex network radiating from London with 3rd rail, 750 volts d.c. before the war and there were other limited schemes (Manchester-Sheffield-Wath was started pre-war but couldn't be completed until after the war) but no major main-line route. Post-war, many other countries went straight for the electric option. At least when the first scheme was announced from Euston to Manchester, we chose a.c. rather than d.c. and high voltage, generally 25 kV, rather than low voltage. This decision was based on the success of a pilot scheme in the Morecambe area briefly outlined in my post Steam around Morecambe. Yet even today, much of the system is not electrified, resulting in a massive mileage by diesel trains even on routes which have been electrified.

Signalling

A Midland Railway signal box preserved at Darley Dale on Peak Rail.

I was very lucky to get to work manual signal boxes (unofficially) in the late 'fifties and 'sixties before the great changes swept over British Railways. My post Visiting Signalboxes has links to more articles about some of the boxes I went to. The early manual signalling systems had had various electrical safeguards added piecemeal but the system still depended upon the integrity of a large band of signalmen. But over a period of time, boxes were abolished, and colour light signals, continuous track circuiting and Power Signal Boxes covering wide areas were introduced. Many of my posts are dedicated to signalling for railways 'Ancient and Modern' - you can find them under the label Railway Signalling.

Saturday, 12 January 2013

My First Trip to India (continued)

In the earlier post My First Trip to India I briefly wrote about my first experience of India when I was assisting G.E.C. in commissioning telecommunications equipment for the Delhi Ring Project. I thought it was time to add a little more.

I flew to Delhi in May 1992, in the height of summer, returning nearly seven weeks later just as the Monsoon arrived in Delhi. It was a very hot summer in Delhi that year - temperatures of 45 degrees Celsius (114 degrees Farenheit) are expected but it seemed that every day people in the G.E.C. office which was our base said "It's 120 today!".

The Delhi Ring Project

G.E.C. were installing a new Electronic Control Centre (ECC) near New Delhi station to control the complex railway network in the area operated by Northern Railways. This included a circular suburban line called the Delhi Ring together with a number of main lines radiating from Delhi. Various new telecommunications cables had already been provided from the ECC along the routes to be controlled and selective ringing omnibus telephones had been supplied by others and installed at signal boxes, stations and level crossings. When GEC started to commission the new telecommunications facilities, a number of problems with the audio transmission were revealed.

At that point my company, Ford Electronics, became involved. We were invited to propose changes simple enough to be retro-fitted on site which would provide good-quality speech throughout the system. Our solution involved the use of Loaded Cable Pairs, correct Build-Outs at equipment locations and a number of 2-wire Amplifiers to restore correct signal levels.

The re-arranged telecommunications circuits are shown in the sketch below.

Click on image for larger view

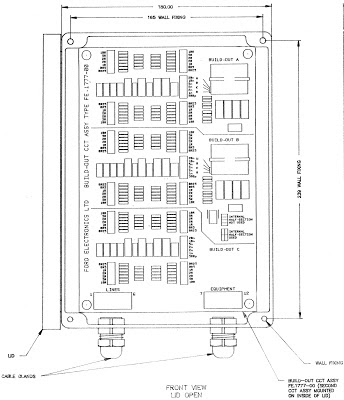

On a short timescale we acquired the necessary 2-wire amplifiers and both designed and constructed the necessary Build-Out Units. Each unit had provision for three build-outs and these could be readily configured to suit each location by a series of links. The Build-Out Unit was in the form of a single assembled printed circuit board mounted in a rugged plastic housing intended for wall mounting adjacent to the telecommunications terminations in the various equipment rooms. The drawing below shows the appearance of the Build-Out Unit with the lid removed.

Click on image for larger view

In the various equipment rooms, the equipment which was added as described above was wall-mounted on a wooden board, seen on the right in the picture below.

Railways around Delhi

As I commented in the earlier post, I was amazed to find steam haulage was still in use since I'd assumed all steam had been eliminated and yet here I was, transported back to the '60s when steam was being eliminated in Britain. On my return to the U.K., a short article entitled 'Steam in India' was published in the September 1992 edition of 'Lionsheart' (the Occasional Newsletter of the Old Locomotive Committee). Since this is the only contemporary account of my visit, I thought it might be worth repeating a section of the article here:-

I saw a little of Indian Railways as they are today today. New Delhi station is all diesel and electric. Electrification is 25 kV a.c. and I was able to travel on 'the fastest train in India' - the electric-hauled Shatabdi Express - at least as far as Agra.This picture appeared in the July 1992 of 'Lionheart', with the caption "Our photograph shows Jan Ford in India recently, looking surprisingly happy after suffering a signal check whilst at the controls of a broad gauge Class WP 'Pacific' from Delhi to Shahdara".

But Delhi Junction still has a number of steam workings. There's a metre-gauge terminus served by steam and diesel standing next to a broad-gauge through station with steam, diesel and electric workings.

Europeans are regarded with friendly curiosity and I found it easy to be invited onto the footplate but soon discovered that not all drivers speak English! However, English names seem to be used for the driving controls so I was able to establish my unlikely credentials as a female enthusiast by the 'Naming of Parts'. Whilst photographing a metre gauge light engine during a lunch break (a Class 'YG' 2-8-2), the driver signalled me to engage reverse gear and open the regulator. I happily pottered out of the platform, thinking we were carrying out a shunt. It eventually dawned on me that we were 'Rightaway the Shed' a few miles distant for disposal! It took a little time at the shed to locate an English speaker and arrange a trip back to my starting point on a diesel-hauled empty stock working, but it was a wonderful, if unexpected, experience.

My friends at railway headquarters said that they would arrange an official footplate trip for me, but they were not so sure about my request for 'hands-on'. In the event, because of pressure of work, it was 6 p.m. on the day I was leaving before I was able to make my official footplate trip.

They'd chosen a steam-hauled Delhi - Haridwar working. As always, the platform was crowded as I made my way along the length of the train to the locomotive - a broad-gauge class WP 'Pacific'. This Indian Railways Standard design was only introduced in 1947, so it is rather modern by OLCO's standards. But perhaps the Editor will find space in a future edition for a description of my all-too-short trip.

National Railway Museum, Delhi

It was on this trip that I made my first visit to the National Railway Museum in New Delhi. The section of the 'Lionsheart' article dealing with the Museum is repeated below:-

My recent business trip to India gave me an opportunity to visit the Railway Museum at New Delhi and see the twilight of steam on the main line around Delhi.This picture of 'Fairy Queen' (along with other pictures) appeared in the July 1992 edition of 'Lionsheart'.

The most famous exhibit in the Railway Museum at Chanakyapuri is 'Fairy Queen', built by Kitson, Thompson and Hewitson in 1855. At one time she was regarded as the oldest steamable locomotive in the world. She was saved through the intervention of Mike Satow, who remains a respected consultant to the museum. This locomotive and a half-sectioned 'A' class broad gauge 4-6-0 share a glass-fronted building of their own. Smaller items and models are housed in a roundhouse-style museum building. All the other exhibits are displayed around a ten-acre outdoor site.

By coincidence, the last issue of LIONSHEART carried a letter from Mike Satow pointing out the link between LION and 'Fairy Queen' in that both locomotives have back-to-front reversing levers. 'Fairy Queen' is built for the Indian 5ft 6in broad gauge, which gives her a squat, powerful appearance. The running boards running the length of the locomotive are noteworthy. Water is carried in well tanks (like 'Bellerophon').

The French built 'Ramgotty' is interesting, both for her wooden brake blocks and Gooch motion operated from outside eccentrics (shades of 'Bellerophon' again).

There are a number of British-built locomotives. The largest locomotive is the Manchester-built Beyer Garrett from the Bengal Nagpur Railway. I imagine our friends at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester would be delighted to repatriate that one!

The oddest exhibit is probably the Patiala State Monorail Trainway locomotive, running on a single guidance rail in the centre with two unflanged wheels on the outside. Built in 1908, this locomotive is still steamable.

An excellent guide to the exhibits at this museum, written by Mike Satow, can be found in the May 1977 edition of 'The Railway Magazine'.

I made another visit to the Railway Museum in February 2006 and the pictures I took on the second occasion are linked in the 'Photographs' section below.

Sightseeing

In the whole time I was there, we worked seven days a week to get the job finished. Time off was confined to a few half-days and two whole days. The first whole day off was a Public Holiday. This gave me the opportunity to visit Agra by train. I went to the Taj Mahal, the Red Fort, the 'Baby Taj' and Fatepur Sikri.

The Taj Mahal at Agra.

On the second day off I was even more ambitious and flew to Varanasi, the Holy City on the River Ganges which was formerly called Banares.

The city of Varanasi, viewed from the River Ganges.

Links to Sets of Photographs

Broad Gauge around Delhi.

Shahdara Junction, Delhi.

Metre Gauge around Delhi.

Driving a 'WG' in India.

National Railway Museum, Delhi (1992)

National Railway Museum, Delhi (2006)

Delhi Ring Project

Varanasi, India.

Thursday, 10 January 2013

Crewe North Junction (1940) Signal Box

A modern view of Crewe North Junction Signal Box, still in situ but now forming part of Crewe Heritage Centre and overshadowed by the overhead electrification structures.

Crewe North Junction Signal Box controlled movements at the North end of Crewe Station from 1940 to 1985. The signal box has been preserved in situ and now forms a major exhibit at Crewe Heritage Centre. This 'ARP' box, with two large Westinghouse Style 'L' Power Frames, is the last-but-one in a series of signal boxes which have controlled the important junctions at the north end of Crewe Station. There's a very brief history of these signal boxes here.

In 1938, with the threat of war and aerial attack looming, it was decided that certain strategic signal boxes should be replaced by an 'ARP' ('Air Raid Precautions') design, better able to withstand blast damage. Accordingly, Crewe North Junction signal box was rebuilt, replacing the earlier 1907 signal box which used the 'Crewe' All Electric System with electric operation of points and semaphore signals.

Westinghouse Brake and Signal Company had been supplying the Style 'L' miniature lever frame since 1929 so it was a 'safe' choice. The L.M.S. order for Crewe North Junction (together with a second for Crewe South Junction and a third 'Standby' frame) was placed in March 1939. The following month, further orders were placed for two more Style 'L' frames for the resignalling of Preston. The Preston project never went ahead and the equipment ended up being used at Euston after the Second World War! Finally, a further frame was ordered for Liverpool Lime Street in January 1940.

The Crewe North Junction lever frame order called for 214 levers made up of 65 point levers, 120 signal levers, 7 'special' levers, 12 spare levers and 10 spare spaces. These levers were divided between two lever frames mounted back-to-back, with a walkway in between to allow maintenance, on the first floor of of the building (the 'operating floor'). A series of windows allowed the signalmen to actually observe the trains they were controlling.

Detail showing miniature levers. White are spare, Red are signals, Black are points. The lamps on the almost vertical panel behind the levers are repeaters.

Movement of each lever drives a vertical shaft via bevel gears. The vertical shaft carries the electrical contacts used for control and interlocking.

With covers removed, the bevel gears which drive the vertical 'drum' of contacts can be seen.

The associated relays which provide the electrical interlocking are mounted on steel shelves in a large Relay Room on the ground floor. 'Shelf' relays are used, interwired on site.

One aisle in the large Relay Room. Shelf-type relays (inter-wired on site) fill the metal shelving.

Looking at Crewe North Junction box from the platforms when I was young, I thought it looked mysterious, with its unfamilar architecture sitting out-of-reach across the maze of trackwork. Finally, I got to visit the box in the 1970s two or three times when my firm had started supplying telecommunication equipment to the railways.

In 1985 control of the Crewe area was transferred to an industrial building painted red and white looking more like a fugitive 'B&Q' than a Signalling Centre. I feared for the future of the redundant 1940 Crewe North Junction signal box but, remarkably, it has survived as part of Crewe Heritage Centre.

In December 2008, I returned to Crewe North Junction box, which is looked after by a group of ex-railwaymen and enthusiasts and I was invited to 'signal' a few moves on the Style 'L' Power Frame.

References

'The Style L Power Frame' written and published by J. D. Francis 1989 (ISBN 0 9514636 0 8).

External Links

Crewe North Junction signal Box (Wikipedia).

Crewe North Junction by Mark Adlington.

My Pictures

Crewe North Junction Signal Box.

Crewe Area.

Tuesday, 8 January 2013

Preparation of Locomotive 'Sapper'

'Sapper' on the outside pit at Rowsley being prepared for the day's running.

In this post, I concentrate on the Driver's duties in oiling and examining the locomotive. Preparation of 'Sapper' is generally similar to preparation of other 'Austerity' tank locomotives, such as Peak Rail's 'Royal Pioneer' (currently posing as '68013') described a few years ago in the post here. The most noticeable difference in 'Sapper' is the use of two 'Wakefield' Mechanical Lubricators to ensure a reliable supply of oil to important parts of the locomotive.

The person oiling the locomotive should always carry a clean rag or woven 'Wiper' to remove any spilt or excess oil. Oil where it shouldn't be will become transferred to the next person to visit that area. In places like the foot framing, spilt oil is likely to be hazardous as it can cause slips. Any dust or ash around will tend to mix with the oil and produce an unsightly and hard to remove coating.

Mechanical Lubricator for Cylinder Oil

A 'Wakefield' Mechanical Lubricator for Compound Cylinder Oil ('Steam Oil') is mounted on the left foot-framing just behind the smokebox. The box-like casting (which is filled with the appropriate grade of clean oil daily or as necessary) has a hinged lid clamped shut to exclude dust and ash. Immersed in the oil are small oil pumps driven from a shaft which passes through a gland to the circular ratchet mechanism marked 'WAKEFIELD' visible in the picture above.

The ratchet mechanism is oscillated back and forth by suitable connections to a reciprocating or rotating part of the motion. In the case of 'Sapper', the Mechanical Lubricators are operated from small eccentric cranks mounted on the crankpins of the leading axle. As the mechanism is oscillated, an internal pawl rotates the shaft through a small angle on each oscillation. Thus, whenever the locomotive is in motion, the pumps are delivering oil through the elbows and copper oil lines visible on the left of the Lubricator. To make sure that the oil lines are 'primed' with oil before leaving the shed, the 'U' shaped bar connected to the shaft is manually rotated a number of times.

This view shows the 'Wakefield' Mechanical Lubricator viewed from the rear of the locomotive. Cylinder oil has quite a high viscosity (usually at least SAE 680) and it can become very viscous in cold weather. The copper pipe on the right is a steam feed to the cock mounted on the foot-framing just behind the lubricator. When the square-headed cock is unscrewed, steam is passed through a heating pipe to warm the oil.

Sight-Feed Lubricator for Cylinder Oil

As built, 'Sapper' will have been provided with just a Sight Feed Lubricator. Where a Sight-Feed, or similar, lubricator is fitted, this is usually mounted on the fireman's side so that makes it more logical for the fireman to look after the 'steam' oil. 'Sapper' has a 'Eureka' Type 'G' single-feed sight-feed lubricator on the Fireman's side of the cab. As I've commented elsewhere, the Great Western Railway regarded sight-feed lubricators as so vital to the running of the engine that the lubricator was always fitted in front of the driver and was the drivers responsibility. To find out more about the G.W.R. approach see the post Summer Saturday with a '2884' and, in particular, the last section titled 'Sight Feed Lubricator'. Normally, once a mechanical lubricator is fitted to a locomotive, no sight feed lubricator would be provided but 'Sapper' has both types and both types are used.

Mechanical Lubricator for Axlebox Oil

A second 'Wakefield' Mechanical Lubricator for Axlebox Oil (often called 'Motion Oil') is mounted on the right foot-framing just behind the smokebox. Construction is similar to the Mechanical Lubricator for Cylinder Oil but the casting is larger to accommodate additional oil lines (in this case six, one per axlebox. In this case, the window showing the oil level faces outwards and can easily be checked during preparation (there is a check window on the Mechanical Lubricator for Cylinder Oil but it faces the centreline of the engine).

Oiling Round

Of course, checking the oil level in the Mechanical Lubricators and priming them is only one task. There are six oil cups on the coupling rods to be filled and two holes to place oil on the Gradient Pins.

There is an oil box on the framing either side behind the smokebox delivering oil to each piston gland and each valve gland. There are two oil boxes (left and right) on the frame stretcher which serves as a motion plate. Each oil box has four oil lines delivering oil to the front and rear of the upper slide bars associated with each cylinder. There are oil cups closed with corks on the two little ends and two more on the valve rods where they pass through the motion plate. I find I can best reach these last points by lying on the foot framing and reaching into the motion but each person has to find a method which suits their build, reach and fitness. On 'Sapper' there are also two oil boxes (left and right) fitted further back just above the frames. Each has three oil lines feeding oil to the hornguides. The right hand one is best reached from outside, but the left one I tend to defer until I'm between the frames, described next.

The next bit I find the hardest. Starting on the foot framing on the fireman's (left) side, I lower myself in between the frames behind the weighshaft and ahead of the crank axle, standing on the brake rigging facing the rear of the engine. How easy this is depends on the 'angle' that the motion is sitting at. In the picture, the right crank is near front dead centre and the left crank is near the top. With luck, the oil cups closed with corks on the two big ends and the four eccentrics can be dealt with, hopefully without dropping a cork into the pit.

Then, I try to turn round so as to face the front of the engine. If the left hand crank is anywhere near the top, I usually end up sitting on the connecting rod. The picture shows the four lifting links suspended from the 'arms' on the weighshaft. Pairs of lifting links are attached to the left and right curved, slotted expansion links. The top of the each expansion link is connected to the associated foward eccentric rod, the bottom of each expansion link is attached to the associated reverse eccentric rod. The picture gives a fair idea of the rather poor access. There are a number of oil holes to be dealt with - at the top and bottom of the lifting links, at the top and bottom of the expansion links and on each dieblock (to provide lubrication to the machined faces of the curved slot in the expansion link). Those are the major oiling points but, as described in the earlier post, there are other points which may benefit from the judicious application of oil.

On locomotives fitted with a steam brake, there is usually a small oiler near the boiler backhead, positioned in the steam line to the steam brake cylinder. 'Sapper' has a cylindrical oiler, normally dealt with by the Fireman by filling it with Cylinder Oil during preparation. This oil is allowed to find its way to the brake cylinder, with the aim of avoiding a 'stuck piston'.

Examination

As important as careful attention to oiling is the 'Daily Exam'. Every part of the construction should be studied during preparation, looking for anything unexpected - something becoming detached, unusual wear, missing split pins or nuts, anything broken, loose or showing signs of cracking (particularly on the springing), anything out of alignment. Time spent in examination at this stage reduces the chance of embarrassment later due to a failure. A pit greatly assists a proper examination, allowing wheels, axleboxes, springs and spring hangers to be closely examined. The picture shows the view forward from just in front of the firebox. The connecting rods are left and right and the two reverse eccentric rods are in the middle, closest to the camera with the expansion links behind. The motion plate is in the background.

Photographs

Larger versions of all the pictures in this article (plus other pictures of the locomotive) can be found in the set below:-

'Sapper' Austerity Tank Locomotive