skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Background

Ukraine has an extensive railway system to the Russian gauge of 5 feet and, although Ukraine has been a sovereign state since 1991, the railway infrastructure and rolling stock was principally provided by Russia during the Tsarist and Soviet eras.

My post Ukraine 2005 briefly describes my trip to Ukraine in 2005 to drive Russian-built steam locomotives. After a long interval, I added more detail in a series of posts starting with Driving Steam in Ukraine (Part 1). The last day of our driving in Kolomiya and our journey by overnight train back to Kiev is described here.

Events of Friday, 28th October 2005

On our arrival in Kiev, the trip organisers (East Europe Railtours Limited in the U.K. and Dzherelo SPK in Ukraine) had arranged visits to two Railway Workshops.

Kiev Railway Works (Passenger)

This works dealt with heavy maintenance to passenger locomotives. The entrance to the works was near the south east end of Kiev main station. We stopped to admire the only surviving 'FDp20' steam locomotive, displayed on a very elaborate welded steel plinth, suggesting a girder bridge. There's a little more about this locomotive class in Loco-profile 3: Russian 'FDp20' class 2-8-4.

The remaining FDp class 'plinthed' at the entrance to Kiev Locomotive Works (Passenger).

The remaining FDp class 'plinthed' at the entrance to Kiev Locomotive Works (Passenger).

Before entering the works, we watched the comings and goings on the main line and looked at the outside of the 8-road locomotive roundhouse.

A variety of electric traction outside Kiev Main Station. Note the decorative fencing and the shrubs.

A variety of electric traction outside Kiev Main Station. Note the decorative fencing and the shrubs.

The depot roundhouse. Note the overhead catenary for each road.

The depot roundhouse. Note the overhead catenary for each road.

In the first works building there were various types of electric locomotive, including an elderly 'Skoda'.

An elderly Skoda ChS4 Co-Co 25 kV a.c. electric locomotive, number 049. These were built between 1966 and 1972 and featured a fibreglass body but were being rebuilt to extend their life.

A rebuilt Skoda ChS4 Co-Co 25 kV a.c. locomotive, number 026.

A rebuilt Skoda ChS4 Co-Co 25 kV a.c. locomotive, number 026.

Jan in the Driving cab of rebuilt Skoda ChS4 Co-Co electric locomotive, number 026.

Jan in the Driving cab of rebuilt Skoda ChS4 Co-Co electric locomotive, number 026.

A separate 'shop' dealt with repairs to the driver's air brake application valve. This was a lofty room with large curtained windows, a domestic wall clock, rather dated light fittings incorporating fluorescent tubes and a potted plant.

The Brake Valve Shop.

We walked through a corridor (where a large artwork had been placed to encourage workers) to look at the shop where Speed Recorders were refurbished. An adjacent shop dealt with the re-machining of the discs for brake application valves (to keep them air-tight). We then passed through the erecting shop for electric locomotives, provided with an overhead travelling crane, inspection pits and high-level access platforms to get to roof-mounted equipment.

The Erecting Shop.

The Erecting Shop.

One pit was provided with a wheel lathe for re-profiling tyres whilst the wheelset was still mounted on the bogie. There were various parts littered around - complete motors, a 'Scissors' pantograph, motor armatures awaiting attention. Nearby, an almost-deserted machine shop had a veteran selection of large lathes and machine tools. Another shop was re-furbishing the large Blowers used on electric locomotives. There were at least three men intently working away here. I noticed a small electric hoist had been slung from one of the steel roof beams, to ease the handling of the bulky fan assemblies. In another long corridor, there was another large artwork - this one of a smiling, athletic young woman. As we left the Workshops, we passed the Conservatory - in the U.S.S.R., large factories commonly had Conservatories so that workers were able to enjoy Nature even in harsh weather.

The Conservatory.

The Conservatory.

Finally, we passed a suitably-heroic mosaic near the entrance to the Works.

The mosaic near the entrance to the Locomotive Works.

The mosaic near the entrance to the Locomotive Works.

The rather run-down appearance of the buildings and the various inspirational artworks certainly suggested how I imagine the U.S.S.R. was after the gruelling years of the second world war. The Works have clearly lacked recent investment, but it was impossible not to be impressed by the skills of the people working there.

Kiev Railway Works (Freight)

A coach took us to the second works, which handles heavy maintenance of freight locomotives. It took almost an hour to reach the site - traffic in the city was heavy and our destination was on the outskirts of Kiev. I think the site served as a running depot for both diesel and electric traction, for in the extensive yard, we found both electric and diesel locomotives. In the Repair Shops, we only saw diesel locomotives under repair. A hand-painted plan of the yard was on display.

Plan of the Yard.

Plan of the Yard.

In the yard, there was a Type VL80 2-section Bo-Bo 25 kV a.c. electric locomotive, number VL80s288. The 's' isn't clear in the picture but the cab side also carries the later number 12505764 in the Russian 1984 numbering system (briefly explained here) which appears to confirm the sub-type as 's', meaning that two 2-section locomotives could be connected in multiple. A second VL80 (VL80t1324) was of the 't' sub-type with rheostatic braking.

View of the yard with a Type VL80 2-section Bo-Bo 25 kV a.c. electric locomotive. The two tall towers in the background appear to be built using pre-cast concrete sections.

View of the yard with a Type VL80 2-section Bo-Bo 25 kV a.c. electric locomotive. The two tall towers in the background appear to be built using pre-cast concrete sections.

Another VL80 in the yard (VL80t1324).

Another VL80 in the yard (VL80t1324).

Diesel traction was represented in the yard by a 2-section Co-Co diesel electric 2TE116-1365 and a 750mm gauge diesel electric locomotive (TU2-165) loaded on a 5 foot gauge flat wagon for transport. About 300 of these narrow gauge locomotives were made, but they were not particularly successful. You can read more about the TU2 on Dimitry Zinoview's interesting site here.

2-section Co-Co diesel electric 2TE116-1365.

2-section Co-Co diesel electric 2TE116-1365.

750mm gauge diesel electric locomotive (TU2-165) loaded on a 5 foot gauge flat wagon.

750mm gauge diesel electric locomotive (TU2-165) loaded on a 5 foot gauge flat wagon.

We made our way through a rather gloomy roundhouse where I examined the cab of what I think was a ChME3. Outside the roundhouse was a colourful line-up of TEM2-7052, ChME3-1296 and ChME3-1811, all Co-Co diesel electrics. The turntable was painted in the blue of the Ukrainian flag and the picture below shows the portal frame in the centre of the turntable crowned with a rotating connection box for the overhead electric cable. The picture also shows two of the smaller Bo-Bo diesel electric shunting locomotives ChME2-322 on the left, ChME2-431 (in rather faded green) on the right. This class, built by CKD in Czechoslovakia, has a 4-stroke 6-cylinder diesel engine developing 552 kW. I assume the modern straight shed in the background of the picture is a running shed, since it is topped by six sand towers (patriotically painted in the Ukrainian flag colours of blue and yellow). There are two more tall towers in the background built with pre-cast concrete sections.

TEM2-7052, ChME3-1296 and ChME3-1811 outside the roundhouse.

TEM2-7052, ChME3-1296 and ChME3-1811 outside the roundhouse.

The roundhouse electric turntable. Left: ChME2-322, Right: ChME2-431.

The roundhouse electric turntable. Left: ChME2-322, Right: ChME2-431.

We moved back inside the older, straight shed which serves as the erecting shop. We examined a moveable portal crane, used for lifting wheelset/motor sub-assemblies and admired a delightful four-wheel railcar marked 'ACIA N3285' which I suspected was used as an Inspection Saloon.

Crane, with wheelset/motor sub-assembly.

Crane, with wheelset/motor sub-assembly.

Railcar ACIA N3285

Railcar ACIA N3285

We found numerous other ChME3 Co-Co diesel electric locomotives around, in various states of 'undress'. Over 7,000 (with various sub-classes) were built by CKD in Czechoslovakia, using the CKD type K6S310DR 4-stroke 6-cylinder diesel engine developing 993 kW. The pictures below shows the engine with all the engine cowling removed and the size of each of the six pistons required to develop this power.

CKD K6S310DR engine.

CKD K6S310DR engine.

Piston/crank used on K6S310DR engine.

Piston/crank used on K6S310DR engine.

After our two fascinating visits to workshops, our coach struggled through the traffic again, to take us to our hotel on Independence Square. There was time for a little sightseeing later in the day and the following morning, before we were taken to the airport for our flights home.

Russian Railway background

At the time of my visit in 2005, I was almost completely ignorant about Russian Railway practice. The book 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' (reference [1] below) is an invaluable primer on Russian steam, diesel and electric traction. In 2011, a river cruise from Moscow to St. Petersburg (described in a series of posts here) gave me tantalising glimpses of railways in Russia. Then, in 2011, I travelled by the 'Golden Eagle' private train from Ulaan Baatar to Moscow (described in a series of posts here).

Book References

[1] 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' by A J Heywood & I D C Button (Frank Stenvalls Forlag) ISBN 0-9525202-0-6.

Photographs:

The railways:

Ukraine Steam.

Ukraine Modern Image.

Kiev Locomotive Works (Passenger).

Kiev Locomotive Works (Freight).

The country:

Ukraine.

In Part 4 I described my third day on the footplate at Kolomiya in Ukraine on 26th October 2005, when Er797-86 and Em735-72 double headed our train to Vorokhta and back.

On Thursday 27th October 2005, the format of the day was similar but this time the run was terminated at Mikulichin.

Into the Mountains again

As before, Er797-86 was leading from Kolomiya with Em735-72 tender first. This time, our train comprised a bogie hopper wagon, a bogie flat wagon and one of the two green coaches Su251-86 had brought from Chernivtsi. The trip the previous day had given us a little 'route knowledge' and were able to start to anticipate.

We made our way through Delyatin and Yaremcha and continued our climb as far as Mikulichin.

Yaremcha station building.

Yaremcha station building.

View ahead from Em 735-72 leaving Yaremcha.

View ahead from Em 735-72 leaving Yaremcha.

I commented about the poor quality of coal in Part 4. As time went on, the situation got worse as all the loose coal became used. We spent some time in the tender with shovels breaking-up the concrete-like contects, trying to release coal which stood a chance of burning. I never really got used to the firing shovels in use. Rather than the 'T' handle of English shovels, where you can use the palm of your hand to either drive the shovel blade into the coal stack or propel a shovelful to the front of the firebox, the Ukraine shovels had a long, straight handle which I found difficult to use.

Typical firing shovel.

Em 735-72 being fired.

Em 735-72 being fired.

On arrival at Mikulichin, we ran the engines round the train ready for the return journey. There was time for me to take more pictures around the station and our train before we set off back to Kolomiya.

Our train at Mikulichin, ready to return to Kolomiya

Our train at Mikulichin, ready to return to Kolomiya

On the return journey, the group with Mike and I was once again on the lead engine, Em 735-72, taking it in turns to drive.

Em 735-72: Fireman's view ahead. The door giving access to the foot-framing is partly open.

At Yaremcha, we passed a 2M62-class diesel electric with a single coach, which I thought might be a dormitory coach for track workers. At one point, when I was driving, we passed a group of track workers, standing clear. We solemnly saluted one another and it reminded me that the unspoken comradeship between railwaymen is not peculiar to the English.

Passing 2M62-1070 with a single coach near Yaremcha.

Passing 2M62-1070 with a single coach near Yaremcha.

This was the fourth day that steam trains had been seen on the Rakhov line and I had started to notice how many people in the lineside properties were outside as we passed, watching the train go by, just as in England when steam specials appear on the main line.

I was driving as we approached the junction at Kolomiya where the line from Ivano Francovsk converged on our left. I looked out for our colour light signal which was showing 'off' but with a 'Green Bar' lit. I realised that we were being crossed into the 'loop' platform and shut off in plenty of time. We clattered over the points leading to the 'loop' and drifted along the platform, with only light braking needed to stop where the Ukrainian driver indicated.

And so our steam driving experience in Ukraine had come to an end. Not all of the arrangements had worked out during the week but I still found it a wonderful experience. We sadly said our "goodbyes" to our Ukranian railway friends, checked out of our hotel and were taken by coach back to Ivano Francovsk. We had a short time to look around the town before entering the railway station to catch our overnight train to Kiev. This time, my booking arrangements worked and I had a 4-berth compartment to myself.

My 4-berth compartment on the Kiev train.

My 4-berth compartment on the Kiev train.

On arrival in Kiev, we were to visit two railway repair works (described here) and spend a night in a hotel before flying home.

Russian Railway background

At the time of my visit to Ukraine in 2005, I was almost completely ignorant about Russian Railway practice. The book 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' (reference [1] below) is an invaluable primer on Russian steam, diesel and electric traction. Later, in 2011, a river cruise from Moscow to St. Petersburg (described in a series of posts here) gave me tantalising glimpses of railways in Russia itself. Then, in 2011, I travelled by the 'Golden Eagle' private train from Ulaan Baatar in Mongolia to Moscow (described in a series of posts here), finding out a little more about Russia's remarkable railway heritage.

Book References

[1] 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' by A J Heywood & I D C Button (Frank Stenvalls Forlag) ISBN 0-9525202-0-6.

My pictures

The railways:

Ukraine Steam.

Ukraine Modern Image.

The country:

Ukraine.

In Part 3 I described my second day on the footplate at Kolomiya in Ukraine, on locomotive Su251-86.

On Wednesday 26th October 2005, my friend Mike and I made our first excursion onto the single line from Kolomiya to Rakhov. We found out how our hosts had dealt with the problems of 24th October when Er797-86 had got into trouble, short of steam, on the Rakhov line (mentioned in Part 2). The solution adopted was to subsequently double-head the train, with Er797-86 coupled tender to tender with Em735-72. Er 797-86 (chimney leading) would haul the train out from Kolomiya with Em 735-72 (tender first) assisting as required. After running round both engines coupled together at the far end, Em 735-72 (now chimney leading) would return the train to Kolomiya with assistance from Er 797-86.

'E' class background

The 'E' class 0-10-0 had been introduced in 1912 as a development from the earlier 'O' series 0-8-0. Russian-built 'E' class were supplemented in the early 1920s by imported 'E' class from Germany and Sweden. The 'Eu' class was a Russian redesign built in large numbers from 1926 until the 'Em' was introduced in 1931. Modifications to the 'Em' design produced the 'Er' class, more powerful and economical than the 'Em'. This class was built between 1935 and 1957. Altogether over 11,000 of the various types were built. There's a little more information on the class here.

Er 797-86/Em 735-72 stand at Mikulichin.

Er 797-86/Em 735-72 stand at Mikulichin.

A journey into the Carpathian Mountains

Although the organisers had initially hoped that we could travel to Rakhov, in fact we were only allowed as far as Vorokhta (about 90 km from Kolomiya).

On the first leg of the journey out, Mike and I were allocated to Em 735-72, which we'd been on for our first day's driving (described in Part 2). We departed from Kolomiya heading west with a train comprising bogie hopper, bogie open and bogie flat wagons. About 47 km from Kolomiya, we arrived at the junction station at Delyatin, where a direct line from Ivano Francovsk converges. Delyatin had a most impressive station building but only the very narrow, low platforms common at smaller stations.

The impressive station building (and narrow, low platforms) at Delyatin.

The impressive station building (and narrow, low platforms) at Delyatin.

A handful of passengers were waiting and our train stood at Delyatin for about half an hour until a diesel multiple unit travelling in the opposite direction cleared the line ahead.

Er 797-86/Em 735-72 pause at Delyatin.

Er 797-86/Em 735-72 pause at Delyatin.

As we continued, the scenery became far more rugged as we headed into the forest-covered mountains. The picture below shows the view ahead of the train, looking from the footplate through the aperture in the tender cab (Em 735-72 was travelling tender first).

View ahead from Em 735-72.

View ahead from Em 735-72.

The above picture also gives a clue regarding the steaming problems. The coal in the tender was very small pieces - slack. Worse, the dust which accompanies slack had been lying in the tender, exposed to the rain, for goodness knows how long, turning the dust to mud which had then dried like cement. We'd not had major problems on our trip to Stefaneshty or with the Su251-86 on the fairly level route to Chernivtsi, but the route to Rakhov was clearly more demanding. In addition, the amount of ash we'd seen dumped by Em 735-72 at Stefaneshty and by the Su251-86 at Chernivtsi suggested that it wasn't a high grade coal to start with. A good coal for locomotives should have a high calorific value, low content of incombustible ash and low content of harmful elements like sulphur which can produce an 'acid rain' attacking the boiler tubes.

8 km beyond Delyatin, we passed through Yaremcha which is an important tourist centre, with a modernised station. The year following my visit, the Romanised spelling of the name was changed to 'Yaremche' (see Wikipedia here). After a further 10 km, we stopped at Mikulichin, where we had to wait for a 'path'. Mikulichin was as pretty a village as the website here suggests and we spent some time exploring the minor road through the village before returning to the fairly isolated station.

Station approach, Mikulichin.

Station approach, Mikulichin.

Back at the station, the friendly lady stationmaster allowed me to study the signalling and telecommunications facilities. I'll describe what I was able to glean in a later post. After a wait of around two hours at Mikulichin, we finally had our 'path' to enable us to set off on the remaining 16 km to Vorokhta. For this leg, the eight trainees had swopped engines, so Mike and I were now on the leading engine, Er 797-86, again taking it in turns to drive.

Er 797-86 leaving Mikulichin.

Er 797-86 leaving Mikulichin.

Approaching Vorokhta, we passed over a fairly notable modern viaduct. There were sentry boxes at each end, presumably from the Soviet era, but they appeared to be no longer in use.

View from Er 797-86: looking back, approaching Vorokhta.

View from Er 797-86: looking back, approaching Vorokhta.

At Vorokhta, the two locomotives were detached from our train and, coupled together, run round our three wagons ready for the return journey. There was then a 'photocall' as everyone (bar the photographer) posed in front of Em 735-72 as pictures were taken with various cameras.

Em 735-72 and the entire cast pose for photographs.

Em 735-72 and the entire cast pose for photographs.

The Ukrainian crews then invited us to lunch on the footplate of Er 797-86. A wooden table appeared from somewhere and lots of typical Ukrainian food was handed round. It was a very jolly interlude.

Er 797-86: Lunch on the footplate at Vorokhta.

We set off on our trip back to Kolomiya having swopped round again so that Mike and I were once again on Er 797-86. The picture below gives a good idea of the attractive area we were passing through. The train is about to pass over one of the many ungated road crossings. Notice the open wire pole route for telephones.

View from Er 797-86 returning from Vorokhta.

View from Er 797-86 returning from Vorokhta.

I'm afraid I'm unclear exactly which bits of the line I drove personally, but I do remember driving through the tunnel on this line. I usually drive with the sliding side window of the cab (which the Russian locomotives also have) open. Approaching the tunnel, I deemed it wise to slide it shut. The tunnel wasn't a 'tight fit' so conditions weren't bad but there was plenty of steam swirling around the cab. We were on the leading engine, of course, so I don't know whether matters were less comfortable on Er 797-86 behind us!

Fireman's view of the tunnel from the cab of Em 735-72 en route to Kolomiya.

Fireman's view of the tunnel from the cab of Em 735-72 en route to Kolomiya.

The last pictures I took on that day were at Yaremcha. By the time we arrived back at Kolomiya, we'd had an interesting but tiring day. The following day would be our last driving day, and that's described here.

Er 797-86/Em 735-72 at Yaremcha.

Er 797-86/Em 735-72 at Yaremcha.

Russian Railway background

At the time of my visit to Ukraine in 2005, I was almost completely ignorant about Russian Railway practice. The book 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' (reference [1] below) is an invaluable primer on Russian steam, diesel and electric traction. In 2011, a river cruise from Moscow to St. Petersburg (described in a series of posts here) gave me tantalising glimpses of railways in Russia. Then, in 2011, I travelled by the 'Golden Eagle' private train from Ulaan Baatar to Moscow (described in a series of posts here).

Book References

[1] 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' by A J Heywood & I D C Button (Frank Stenvalls Forlag) ISBN 0-9525202-0-6.

Photographs

The railways:

Ukraine Steam.

The country:

Ukraine.

In Part 2 I described my first day on the footplate at Kolomiya in Ukraine, on locomotive Em 735-72.

On Tuesday 25th October 2005, my friend Mike and I were allocated to the Su251-86 which, with a coach and two bogie wagons, was to head south-east to Chernivtsi, about 75 km distant. As I mentioned in Part 1, Su 251-86 is normally based at Chernivtsi and the Ukranian crew were also stationed at Chernivtsi.

Su class background

This locomotive was probably the most 'English' looking of the steam locomotives we saw, although it retains plenty of 'Russian' features. The design was derived from Sormovo Works 'S' class of 1910 via the 1915 'Sv' class from Kolomna Works, re-designed by Kolomna Works in 1925 as the 'Su' class. It became the standard passenger engine for long-distance and suburban work in Russia and over 2,500 were built in four different variants. It was 6-coupled with carrying wheels fore and aft to produce a 2-6-2 (Whyte's) wheel arrangement (although the Russians invariably counted axles, calling it a 1-3-1). With an axle load just over 18 tons, it had good route availability.

The coupled wheels were 1850mm (6'1") diameter. The Russians didn't go in for the small variations of wheel diameter between classes which rather afflicted British designers and the later FDp20 (first built 1932) and P36 (first built 1950) retained the same wheel diameter.

Although elsewhere the vogue was for 4-wheel leading bogies on fast passenger locomotives, for some reason, Russian designers were never keen on the idea and used a 2-wheel leading truck until the 'P36' design of 1950.

English locomotive designers indulged in all sorts of fancy profiles for their chimneys - J. G. Robinson said "The chimney is to a locomotive like a hat to a man - the finishing touch" but the utilitarian designers further east were usually content with a simple tapered 'stovepipe'.

The boiler appears to have two domes but the rear one is a 'Sand Dome' to hold dry sand for application to the rails to improve traction.

A substantial cab is provided, lined with wooden panelling. A prominent feature is a glazed 'skylight' on the cab roof. Access to the cab from the ground is via proper inclined 'stairs' provided with handrails (a distinct improvement on the meagre vertical steps of British designs). The front wall of the cab has doors either side to give access to the footframing and. in common with most Russian steam locomotives, substantial railings are provided around the outside edge of the foot-framing (rather than a single handrail fixed to the boiler, as in British practice).

The class were originally designed for a maximum speed of 115 km/h but the preserved locomotive had been given a much lower limit (40 km/h, I think).

Su 251-86 at Kolomiya Depot.

Su 251-86 at Kolomiya Depot.

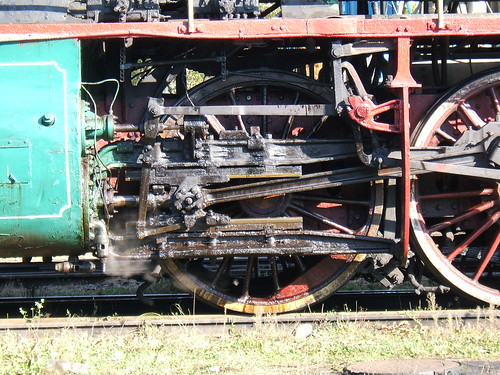

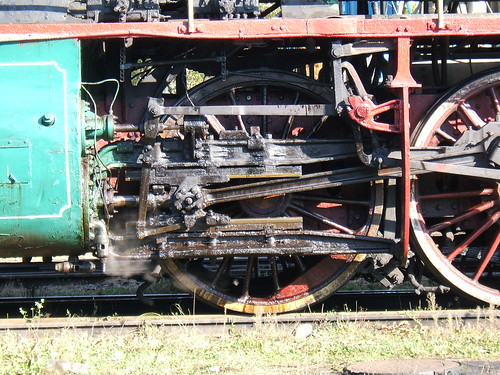

The Su class, like the majority of Russian designs, has two outside cylinders (575mm by 700mm) with piston valves driven by Walschaerts Valve Gear.

Su 251-86: Left hand motion detail.

Su 251-86: Left hand motion detail.

My friend Mike tries out the driver's seat. Russian railways adopt right-hand running on double track, with signals set on the right and locomotives are right hand drive.

The picture below shows the boiler backhead. The general appearance of disrepair was a little worrying but the locomotive operated as required the week that we were there.

The 'skylight' in the roof is visible at the top of the picture. There is a Steam Manifold mounted on top of the firebox, provided with a number of red T-handled shut-off cocks. The two large copper pipes at either end of the Manifold supply steam to the two backhead-mounted injectors.

The gland for the regulator rod is in the normal position, on the centre line of the boiler, near the top of the green-painted cladding. However, rather than attaching the regulator handle directly to the regulator rod, a link connects the rod to a short regulator handle mounted lower down and to the right, so as to be more accessible to the driver. The regulator handle works in a notched quadrant and a catch on the regulator handle allows it to be latched in the desired position. There is one gauge glass, mounted to the left of the regulator gland. As a back-up, there are three 'Try-cocks' to the right of the regulator gland. The dual, sliding firedoors are near the bottom of the picture. Each heavy, cast firedoor is suspended on two greased wheels running on the track above the firehole.

Su 251-86: Detail of boiler backhead.

All the locomotives we saw in Ukraine, including the Su 251-86, had large, 8-wheel tenders carried on two bogies, with a fairly simple 'tender cab' at the front, matching the locomotive cab. On the tender sidesheeting, next to the cab and just above the tender underframe, the darker rectangle is the door to a compartment for storing oil bottles and oil feeders.

Su 251-86 at Kolomiya Depot, showing the bogie tender.

Su 251-86 at Kolomiya Depot, showing the bogie tender.

On the road

Despite the engine's battered appearance, the Chernivtsi crew were clearly proud of it, and I quickly grew to like it. We set off on the single line to Chernivtsi, taking it in turns to drive and assist the fireman. We stopped at an intermediate station and the crew took the opportunity to apply more oil.

Su 251-86: My friend Mike oiling the leading truck en route to Chernivtsi under the watchful eye of the Ukranian driver. The oil feeder in use is much larger than that typically used in Britain.

Su 251-86: My friend Mike oiling the leading truck en route to Chernivtsi under the watchful eye of the Ukranian driver. The oil feeder in use is much larger than that typically used in Britain.

As we approached our destination, it became clear that Chernivtsi was a fairly major city - I think the population was around 240,000 at the time. There is a Wikipedia article here. On arrival at Chernivtsi, we were routed into one of a number of sidings leaving the platforms and the impressive station building on our right.

Chernivtsi Railway Station (built 1909) viewed from the road (Photo: Creative Commons Attribution: DDima).

Chernivtsi Railway Station (built 1909) viewed from the road (Photo: Creative Commons Attribution: DDima).

I think we were offered the opportunity to explore the town but Mike and I preferred to stay with the engine. Having uncoupled our short train and left it in the sidings, the engine was signalled to carry on ahead to reach the motive power depot. After about one kilometre, the single-track main line curved away on our right and a few hundred metres further took us to a complex of sidings and the motive power depot.

Chernivtsi Motive Power Depot

Our locomotive was 'parked-up' in the sidings of what is now a diesel depot and we were allowed to wander around the depot (I think the Ukranian crew were taking their lunch break). A turntable served a roundhouse, built of reinforced concrete with brick infill. The capacity of the shed had been reduced by replacing some of the access doors with solid walls. Repairs had been carried out to the remaining wooden access doors on each road leading into the shed. A class TGK2 diesel-hydraulic shunter number 6009 and a smart-looking ChME3 (but with at least one wheelset missing) stood outside the roundhouse.

My friend Mike examines the repairs to the wooden doors of the roundhouse at Chernivtsi.

My friend Mike examines the repairs to the wooden doors of the roundhouse at Chernivtsi.

A smart-looking ChME3 (but with at least one wheelset missing) standing outside the roundhouse at Chernivtsi.

A smart-looking ChME3 (but with at least one wheelset missing) standing outside the roundhouse at Chernivtsi.

We were drawn to two of the massive class 'L' 2-10-0 freight locomotives, L 3535 and L 5141, standing in the open. Starting in 1945, over 4,000 of these popular freight locomotives were built. I'm afraid close inspection found these impressive machines in the same battered state of all the locomotives we'd seen in Ukraine, although not quite as care-worn as nearby 'Er' class 799-82.

'L' class 2-10-0 numbers 3535 (left) and 5141 (right) in store at Chernivtsi.

'L' class 2-10-0 numbers 3535 (left) and 5141 (right) in store at Chernivtsi.

L: 2M62U-0331, R: (in battered condition) 'Er' class 799-82 at Chernivtsi.

L: 2M62U-0331, R: (in battered condition) 'Er' class 799-82 at Chernivtsi.

This trip to Ukraine was the first time I'd seen the Russian pattern of Sanding Tower shown in the picture below. Much later, in 2012, I found even more impressive installations at Ilanskaya (described here).

The Diesel Preparation Sidings at Chernivtsi with a number of Sanding Towers visible.

The Diesel Preparation Sidings at Chernivtsi with a number of Sanding Towers visible.

In addition to the roundhouse, we found what appeared to be workshops served by a number of parallel roads at one end and a lightweight traverser at the other end. It was possibly a wagon workshop but we didn't find any activity around the building.

Near the workshops, we found a narrow gauge 0-8-0 in store. It appeared to be 159-495, 750 m.m. gauge, formerly at Dnepropetrovsk Childrens' Railway in the Ukraine. The Russian 'Gr' class is similar.

Narrow gauge 0-8-0 159-495 at Chernivtsi.

Narrow gauge 0-8-0 159-495 at Chernivtsi.

The Ukranian crew had turned the locomotive on the turntable for the trip back to Kolomiya and decided to take more coal, so a rail-mounted mobile diesel crane with a grab was summoned and used to 'borrow' coal from the tender of L3535 and transfer it to the tender of Su 251-86!

Coaling Su 251-86.

Coaling Su 251-86.

There was clearly some concern about the effectiveness of the steam turbine generator (mounted on top of the firebox) which is used to power the headlamps and other lamps, including cab lighting. A fitter was summoned and he clambered on top of the firebox and made some adjustments. He could be quite clearly heard repeating "Kaput!" but I think we had electricity on the way home.

A fitter at Chernivtsi attempts repairs to the steam turbine generator.

A fitter at Chernivtsi attempts repairs to the steam turbine generator.

The Ukranian crew also emptied char from the smokebox. The complete flat smokebox front is hinged on the left (looking from the front) and, once unbolted, can be swung open for re-tubing and access to the tubeplate. Regular access for char removal is via a smaller dished door, hinged on the right and secured by a number of 'dogs' or clamps which, when tightened, ensure that the smokebox door is airtight. After the char was removed, I closed the door and tightened the 'dogs', using a side spanner.

Removing smokebox char.

The final jobs before our return trip to Kolomiya were to empty the hopper ashpans and oil round.

Su 251-86 with the hopper ashpan doors open. Note the metal scotch placed under the trailing wheel.

Su 251-86 with the hopper ashpan doors open. Note the metal scotch placed under the trailing wheel.

The Journey Home

It was starting to get dark as we set off, at a leisurely pace, back to Kolomiya. I vividly remember driving on this trip with the hypnotic 'clink - clonk' from the motion as we sauntered along through the darkness. For some reason, the beat made me start quietly singing 'The Rhythm of Life' - one of the songs performed by Sammy Davis Junior in the film 'Sweet Charity'. Even with our electric headlight, there wasn't much to see. Every so often, we passed over level crossings, often without barriers, but inevitably with a wooden lamp post carrying a single fluorescent tube throwing pale illumination onto the crossing itself. All too soon, we were back in Kolomiya after an interesting but tiring day. We were happy to leave the Ukraniam crew to complete disposal and we wearily returned to our hotel.

The next day, Mike and I were to drive on the Rakhov line. That's described in Driving Steam in Ukraine (Part 4).

Russian Railway background

At the time of my visit in 2005, I was almost completely ignorant about Russian Railway practice. The book 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' (reference [1] below) is an invaluable primer on Russian steam, diesel and electric traction. In 2011, a river cruise from Moscow to St. Petersburg (described in a series of posts here) gave me tantalising glimpses of railways in Russia. Then, in 2011, I travelled by the 'Golden Eagle' private train from Ulaan Baatar to Moscow (described in a series of posts here).

Book References

[1] 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' by A J Heywood & I D C Button (Frank Stenvalls Forlag) ISBN 0-9525202-0-6.

Photographs:

Ukraine Steam.

Chernovtsy Motive Power Depot, Ukraine.

In Part 1 I described my journey to Kolomiya in Ukraine on a trip to drive Russian-built steam locomotives.

On Monday 24th October 2005, our footplate experience commenced. The fitters were still working on the leaking tubes on YeA2026 so we had three steam locomotives available. The twelve people on the course were divided into three groups of four to travel on different engines on different routes. The two Engineer's coaches which Su251-86 had arrived with were allocated to two of the trains to provide accommodation.

One group were allocated to Er797-86 which, with bogie wagons as a load, was heading south-west on the Rakhov line.

The second group were allocated to Su251-86 which, with a similar load, was heading south-east for Chernivtsi.

My friend Mike and I, with two others, were with Em735-72, with one of the coaches and two bogie wagons which would head north-east to Stefaneshty.

Railways around Kolomiya.

Of course, each locomotive was under the control of a Ukrainian Driver and Fireman. Since few railwaymen in Ukraine have much English, the problem of communication had been addressed by Dzherelo SPK by providing a bilingual college student on each locomotive to act as an interpreter. The idea was that two of each group would be Trainee Driver and Fireman for a time before swopping roles. The two Engineer's coaches which Su251-86 had arrived with were allocated to two of the trains to provide accommodation for the other two trainees who would exchange with the pair on the footplate at a suitable stopping point.

After the first day, I think the whole group stayed on the footplate and swopped round as necessary. The Russian loading gauge is particularly generous and the cabs were large so this presented no problem. I was reminded of my first time on the footplate of a Broad Gauge steam locomotive in India in 1992 (described here), when I commented at the time that the cab was big enough "to hold a party".

Em 735-72 in the sidings ready to leave Kolomiya.

Em 735-72 in the sidings ready to leave Kolomiya.

We set off, passed the roundhouse and the diesel shed, taking the left of two single lines, with the line to Chernivtsi on our right. The map above shows how sinuous the line to Stefaneshty is, as it winds through rolling hills. The line is something of a switchback too so, having set the regulator and cut-off to the Ukraine Driver's instructions, speed would fall a little on the uphill sections, then pick-up again on the downgrades. I was driving at this point and, although the locomotive might have been a rather battered survivor, I had the confidence that it would just keep clomping along for ever. And, of course, I would have stayed in the right-hand driver's seat for ever but we had three other trainees to share with. All too soon, we were arriving at Stefaneshty. The single line from Luzhany (on the direct line from Kolomiya to Chernivtsi) converged on our right and we were routed into the rightmost loop line, where we stopped opposite the station building. With our winding route from Kolomiya, we must have travelled around 80 km.

Em 735-72 on arrival at Stefaneshty.

Em 735-72 on arrival at Stefaneshty.

The Ukrainian Fireman immediately set-to emptying ash from the ashpan, whilst his driver oiled round the motion again. I don't know whether the ashpan had been emptied the previous evening, but there was certainly plenty of ash dumped between the rails at Stefaneshty. The fireman detached the locomotive from its train (one air brake hose to disconnect, then pull the release lever to open the knuckle on the massive Russian-pattern automatic coupler) and the Ukrainian Driver ran the locomotive around its train.

Em 735-72: Oiling round and Ashing-out at Stefaneshty.

Em 735-72: Oiling round and Ashing-out at Stefaneshty.

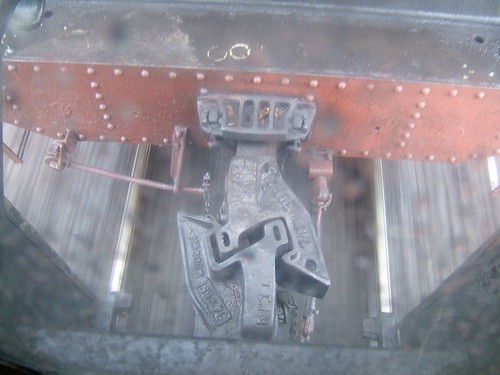

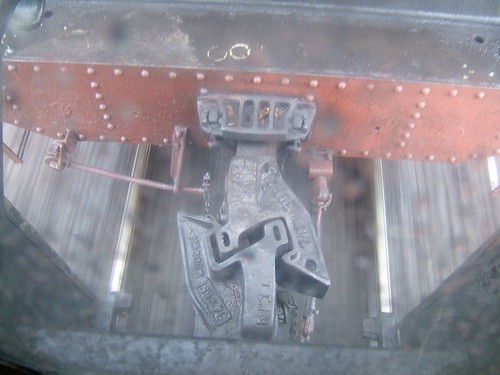

We set off in the opposite direction, this time with Em 735-72 running tender-first. At the south end of Stefaneshty, we were routed onto the left-hand single line to Luzhany, leaving the line we'd travelled earlier on our right. A journey of about 35 km took us to the junction at Luzhany where, once again, Em 735-72 was run around its train. The engine was now chimney-leading again, for the last leg of about 60 km back to Kolomiya. I know that Mike and I travelled in the coach for at least part of this journey, because I was able to take a picture of the standard Russian Autocoupler.

Em 735-72 at speed in the rain, showing Russian pattern autocoupler between tender & coach. The release lever to open the knuckle on the coupler is on the left and the air brake hose (with two red-painted 'palm' couplings between the vehicles) is just to the right of the Automatic Coupler.

Em 735-72 at speed in the rain, showing Russian pattern autocoupler between tender & coach. The release lever to open the knuckle on the coupler is on the left and the air brake hose (with two red-painted 'palm' couplings between the vehicles) is just to the right of the Automatic Coupler.

We arrived back at Kolomiya safely, as did Su251-86 returning from Chernivtsi. But we learnt that Er797-86 had got into trouble on the Rakhov line, short of steam, causing some disruption to the public trains and resulting in a late arrival back in Kolomiya. Further disappointing news was that, since YeA 2026 had failed another steam test, there was insufficient time to cool the boiler down, carry out remedial work, light it up again and carry out a further steam test before the end of our visit. With great regret, YeA 2026 was 'scratched'.

YeA 2026 left to cool-down after failing the steam test.

YeA 2026 left to cool-down after failing the steam test.

We returned to our hotel for an evening meal and bed, because we had another early start the following day when we'd do it again.

Continued in Driving Steam in Ukraine (Part 3).

Russian Railway background

At the time of my visit to Ukraine in 2005, I was almost completely ignorant about Russian Railway practice. The book 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' (reference [1] below) is an invaluable primer on Russian steam, diesel and electric traction. In 2011, a river cruise from Moscow to St. Petersburg (described in a series of posts here) gave me tantalising glimpses of railways in Russia. Then, in 2011, I travelled by the 'Golden Eagle' private train from Ulaan Baatar to Moscow (described in a series of posts here).

Book References

[1] 'Soviet Locomotive Types - The Union Legacy' by A J Heywood & I D C Button (Frank Stenvalls Forlag) ISBN 0-9525202-0-6.

My Pictures

Ukraine Steam.

The remaining FDp class 'plinthed' at the entrance to Kiev Locomotive Works (Passenger).

The remaining FDp class 'plinthed' at the entrance to Kiev Locomotive Works (Passenger).

A variety of electric traction outside Kiev Main Station. Note the decorative fencing and the shrubs.

A variety of electric traction outside Kiev Main Station. Note the decorative fencing and the shrubs.

The depot roundhouse. Note the overhead catenary for each road.

The depot roundhouse. Note the overhead catenary for each road.

A rebuilt Skoda ChS4 Co-Co 25 kV a.c. locomotive, number 026.

A rebuilt Skoda ChS4 Co-Co 25 kV a.c. locomotive, number 026.

Jan in the Driving cab of rebuilt Skoda ChS4 Co-Co electric locomotive, number 026.

Jan in the Driving cab of rebuilt Skoda ChS4 Co-Co electric locomotive, number 026.

The Erecting Shop.

The Erecting Shop.

The Conservatory.

The Conservatory.

The mosaic near the entrance to the Locomotive Works.

The mosaic near the entrance to the Locomotive Works.

Plan of the Yard.

Plan of the Yard.

View of the yard with a Type VL80 2-section Bo-Bo 25 kV a.c. electric locomotive. The two tall towers in the background appear to be built using pre-cast concrete sections.

View of the yard with a Type VL80 2-section Bo-Bo 25 kV a.c. electric locomotive. The two tall towers in the background appear to be built using pre-cast concrete sections.

Another VL80 in the yard (VL80t1324).

Another VL80 in the yard (VL80t1324).

2-section Co-Co diesel electric 2TE116-1365.

2-section Co-Co diesel electric 2TE116-1365.

750mm gauge diesel electric locomotive (TU2-165) loaded on a 5 foot gauge flat wagon.

750mm gauge diesel electric locomotive (TU2-165) loaded on a 5 foot gauge flat wagon.

TEM2-7052, ChME3-1296 and ChME3-1811 outside the roundhouse.

TEM2-7052, ChME3-1296 and ChME3-1811 outside the roundhouse.

The roundhouse electric turntable. Left: ChME2-322, Right: ChME2-431.

The roundhouse electric turntable. Left: ChME2-322, Right: ChME2-431.

Crane, with wheelset/motor sub-assembly.

Crane, with wheelset/motor sub-assembly.

Railcar ACIA N3285

Railcar ACIA N3285

CKD K6S310DR engine.

CKD K6S310DR engine.

Piston/crank used on K6S310DR engine.

Piston/crank used on K6S310DR engine.