On Saturday 1st June 2013, I made a day trip to Ely by rail to attend the Open University Degree Ceremony in Ely Cathedral (where Ann was "being presented" having graduated). It's a little surprising that such a cross-country journey is feasible these days but there's a regular Birmingham - Stansted Airport service which calls at Ely.

I reached Birmingham using the Virgin service from Wolverhampton. This was more than I could easily have done the previous (Bank Holiday) weekend when Wolverhampton was closed to trains and all departures were by bus. It continues to appall me that chunks of our railway system close down every holiday period for engineering works of one sort or another. This is such a contrast with matters when I was young when the railway put on extra trains and virtually every vehicle that could 'turn a wheel' was pressed into service (there's a flavour of this sort of activity in my post Excursions at Sedgeley Junction). The idea of the railway excursion is credited to Thomas Cook who organised the first known major excursion from Leicester to Loughborough in 1841.

Statue outside Leicester station of Thomas Cook.

Executing the change at Birmingham New Street meant negotiating the recently-changed arrangements there. Birmingham New Street station is being modernised. There's a website here about the project which modestly describes itself as "transforming Birmingham's New Street station to create a stunning 21st century transport hub". Halfway through the project, the first half of the new concourse was opened on the 28th April 2013 so it's all a bit incomplete and unfamiliar.

A class 170 from Leicester arriving at Birmingham New Street in 2009.

A class 170 from Leicester arriving at Birmingham New Street in 2009.

However, the 3-car class 170 diesel multiple unit was already waiting in the platform and we slowly set off 'right time'. Once we'd untangled ourselves from what I still think of as the "new" arrangements around Proof House Junction and established ourselves on the Up Derby, speed picked up. We passed Saltley Power Signal Box and then the futuristic-looking West Coast Control Centre.

Each time I travel by rail now, I'm reminded of just how difficult is is to observe the 'passing scene' from a train since most trains have air conditioning and no opening windows at all. Seats appear to be carefully aligned in relation to the available windows so as to minimise the number of seats with a decent view outside. This makes taking pictures from a moving train - the "drive by shooting" - difficult and the results disappointing. One of the attractive features of the early 'Modernisation' series of diesel multiple units was the window at the end of the passenger compartments allowing passengers to look through the driving compartment to the track ahead (or behind). Of course, that sort of nonsense has been stamped out. In modern diesel-powered trains, the noise and vibration from the underfloor engines is often too high for comfort, as well.

Our train continued on the former Midland Railway route. Approaching Nuneaton, you struggle to spot signs of the former Abbey Street station which I remember, with its all-wood 'Midland' signal box. From here, trains are routed to a new island platform tacked on to the Up side of the largely London and North Western station which serves the West Coast route. Originally, there was a freight avoiding line here which, I think, was sometimes used by passenger excursions.

Nuneaton: View from the new island platform looking south, with the old station on the right.

Nuneaton: View from the new island platform looking south, with the old station on the right.

We made good time to Leicester. I'm always amazed at just how simplified the railway layout is, compared with what I remember from steam days. After a wait of a few minutes, we set off northwards, passing the very spartan-design of the Power Signal Box.

Leicester station, looking north. Click above for an uncropped picture showing the Power Signal Box on the right.

Leicester station, looking north. Click above for an uncropped picture showing the Power Signal Box on the right.

At Syston, we turned right for the Midland Railway line to Peterborough. As we made our way along the branch, I was pleased to see semaphore signals. I spotted the elderly Midland-origin mechanical signalboxes at Market Harborough and Oakham - I'm not sure what others survive.

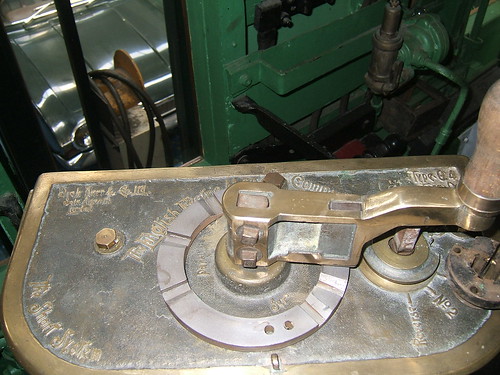

The Midland route approaches Peterborough from the north, meeting the electrified East Coast Main Line about six miles north of the city and then running parallel to it to Peterborough station. There was quite a lot of alteration work in hand around the station. Quite a few passengers alighted or boarded here. Leaving the station, the Midland route diverged from the electrified route to Kings Cross on a falling grade before taking a broad sweep to the left and crossing the River Nene. On the right, I could see 'Railworld', a rather curious amalgam of Transport Centre and Wildlife Haven, "promoting sustainable travel and development". The trackbed of the London and North Western Railway route can be seen. This originally converged with the Midland route here. A few yards to the west I could see the Nene Valley Railway's eastern terminus (called, appropriately enough, 'Peterborough Nene Valley') which is built on that redundant trackbed. We then passed under the impressive girder bridge carrying the electrified lines and, after about a mile and a half, left the control area of Peterborough Power Box. We returned to semaphore signalling, initially controlled by a delightful mechanical signal box at Kings Dyke. We were now in Great Eastern Railway territory and the signal boxes provided a suitable reminder.

The next large town was March, about 15 miles from Peterborough, and we crossed fifteen level crossings (plus a couple of Accommodation Crossings) before arriving at March. I first visited March with my mother when I was about ten years old. She had a visit to make in the area and we travelled by train. I remember an impressive station with elaborate umbrella roofing over the platforms and a selection of unfamiliar Eastern region steam locomotives. Returning in 2013, only two platforms remain in use and the rest of the station is semi-derelict with tracks removed. I think there were originally four through platforms and a couple of bays.

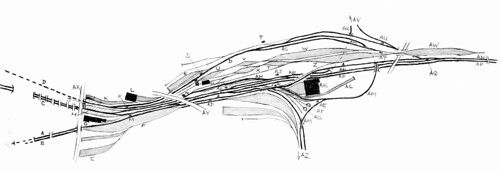

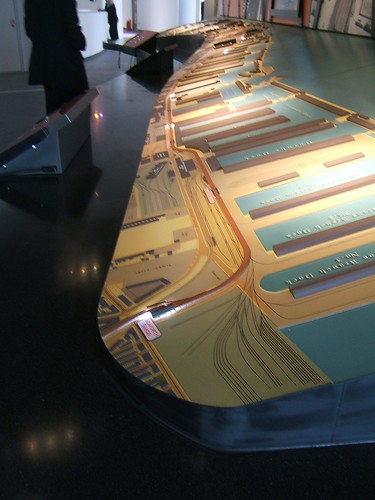

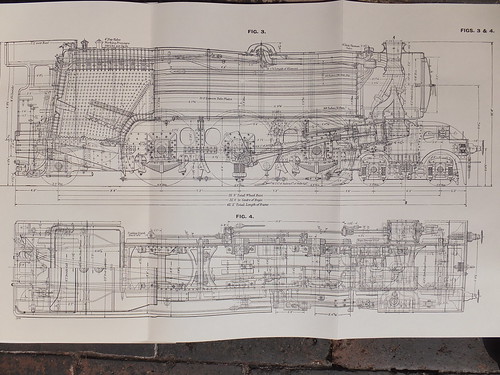

March was famous for its automated hump marshalling yard at Whitemoor, built by the L.N.E.R. in 1929 and well-described in 'Mike's Railway History here.

Whitemoor Hump Yard (from a British Rail Film Strip produced in 1950).

Whitemoor Hump Yard (from a British Rail Film Strip produced in 1950).

I never saw the hump yard and it was completely removed by the mid 1980s. However, a new yard has been built, principally to serve as one of the ugly 'Virtual Quarries' now used for ballast storage.

There are still two mechanical signal boxes at March - March East Junction and March South Junction - controlling a pleasing array of mechanical signals. Beyond March, I didn't spot the boxes at Stonea and Manea but I think they survive, Manea serving as a 'Fringe Box' to the Power Box at Cambridge. Fourteen miles beyond March, the overhead electrified line from Kings Lynn joined on our left at Ely North Junction. This is remotely controlled from Cambridge, as is Ely station itself, two miles further on, where I left the train. The train then continued 'under the wires' to Cambridge and then Stansted Airport.

I had an interesting day as Ann's guest at the Degree Ceremony in Ely Cathedral. Ann and Dean are involved in the Sealed Knot as members of Sir Gilbert Hoghton's Companie of Foote and a number of members of this Royalist regiment attended in costume and posed for photographs, by arrangement, before the Degree Ceremony. This created quite a bit of interest!

Hoghton's in the Nave of Ely Cathedral.

Hoghton's in the Nave of Ely Cathedral.

The ceremony itself started at 2.30 p.m. and almost 300 graduates were presented to the Chancellor of the Open University, Lord Puttnam of Queensgate CBE. In the evening, a further group of graduates were to be presented at a similar ceremony.

A graduate being presented to Lord Puttnam.

A graduate being presented to Lord Puttnam.

Later, John, Ann, Dean and I enjoyed an excellent meal (as John's guests) at 'The Boathouse' riverside restaurant. Then, a short walk took me back to Ely station, where I had time to take a few pictures before catching the 20:15 to Birmingham. At Birmingham, I'd just time to catch a 'Virgin' Pendolino service back to Wolverhampton.

Ely station in the evening: A Class 365 for King's Lynn on the Down Main passes a freight waiting in the Down Goods Loop.

Ely station in the evening: A Class 365 for King's Lynn on the Down Main passes a freight waiting in the Down Goods Loop.

Map References

There are historic signal box diagrams for some of the route I travelled in the Signalling Record Society publications 'British Railways Layout Plans of the 1950's'.

Wolverhampton to Birmingham is included in 'Volume 11: LNW Lines in the West Midlands' (ISBN: 1 873228 13 9).

Saltley to Nuneaton Abbey Street is included in 'Volume 16: ex-MR lines Derby (excl) to Barnt Green, Burton to Leicester (excl), and branches' (ISBN: 1 873228 22 8).

For details of the route in the 21st century, refer to:-

'Railway Track Diagrams Book 4: Midlands & North West', Second Edition, published by Trackmaps (ISBN: 0-9549866-0-1).

'Railway Track Diagrams Book 2: Eastern', Third Edition, published by Trackmaps (ISBN: 0-9549866-2-8).

My pictures

West Midland Railways.

Nuneaton.

Leicester area.

Ely Station.

Ely & the Degree Ceremony.

.jpg)